“The Scene Had a Problem, and the Problem Was the Gun.”

"Stagecoach" (1939), Buffalo Bill's Wild West, Film, Guns, Hollywood, John Ford, John Wayne, Winchester 1892, Yakima Canutt

Scott Eyman, in his new biography, John Wayne, The Life the Legend, describes the historic source of the iconic gesture in the opening scene of John Ford‘s “Stagecoach” (1939), which ignited Wayne’s career and made him a major star.

The scene had a problem, and the problem was the gun.

Dudley Nichol’s script was specific. “There is the sharp report of a rifle and Curly jerks up his gun as Buck saws wildly at the ribbons.

“The stagecoach comes to a lurching stop before a young man who stands in the road beside his unsaddled horse. He has a saddle over one arm and a rifle carelessly swung in the other hand… It is Ringo…

“RINGO? You might need me and this Winchester, I saw a couple ranches burnin’ last night.’

“CURLY? I guess you don’t understand, kid. You’re under arrest.

“RINGO?(with charm) I ain’t arguing about that, Curly. I just hate to part with a gun like this.

“Holding it by the lever, he gives it a jerk and it cocks with a click…”

John Ford loved the dialogue, which was in and of itself unusual, but the introduction of the Ringo Kid needed to be emphasized. Ford decided that the shot would begin with the actor doing something with the gun, then the camera would rapidly track in from a full-length shot to an extreme close-up — an unusually emphatic camera movement for Ford, who had grown to prefer a stable camera.

Since the actor was already coping with two large props, Ford decided to lose the horse. He told his young star what he was planning to do: “work out something with the rifle,” Ford sais. “Or maybe just a pistol.” He wasn’t sure.

And just like that the problem was dropped in the lap of his star, a young — but not all that young — actor named John Wayne., better known to Ford and everyone else as Duke.

Wayne ran through the possibilities. every actor in in westerns could twirl a pistol, so that was out. Besides, the script specified a rifle cocked quickly with one hand, but later in the scene than what Ford was planning. In addition, Ford wanted him to do something flashy, but it couldn’t happen too quickly for the audience to take it in. All the possibilities seemed to cancel each other out.

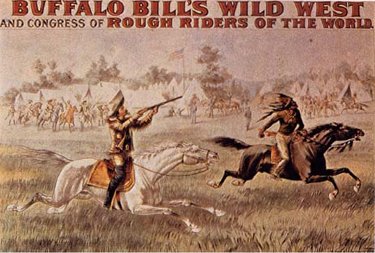

And then Yakima Canutt, Wayne’s friend and the stunt coordinator on the film offered an idea. When Canutt was a boy he had seen Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. As the overland stage raced around the arena, a messenger trailing behind the stagecoach had carried a rifle with a large ring loop which allowed him to spin the rifle in the air, cocking it with one hand. The crowd went wild. Canutt said that it had been done thirty years ago and he still remembered the moment. More to the point, he had never seen anybody else do it.

Wayne sparked to the idea, as did Ford, so they had to make it work. Ford instructed the prop department to manufacture a ring loop and install it on a standard issue 1892 Winchester carbine. After the rifle was modified, Wayne began experimenting with the twirl move as Canutt remembered it, but there was a problem — the barrel of the rifle was too long — it wouldn’t pass cleanly beneath Wayne’s arm.

The Winchester went back to the prop department, where they sawed an inch or so off the end, then soldered the sight back on the shortened barrel.

With that minor adjustment, the move was suddenly effortless. Wayne began rehearsing the twirling movement that would mark his appearance in the movie he had been waiting more than ten years to make — a film for John Ford, his friend, his mentor, his idol, the man he called “Coach” or, alternately — and more tellingly — “Pappy.”

With any luck at all, he’d never have to go back to B westerns as long as he lived.

—————————

—————————

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World.