Category Archive 'Literature'

02 Jan 2021

Emma Hughes, in the inestimably excellent Country Life, looks at the literary cure for the common hangover.

First, she quotes Kingsley Amis’s description of the unhappy problem:

‘Dixon was alive again,’ it begins, with biblical solemnity. ‘Consciousness was upon him before he could get out of the way; not for him the slow, gracious wandering from the halls of sleep, but a summary, forcible ejection. He lay sprawled, too wicked to move, spewed up like a broken spider-crab on the tarry shingle of the morning.’

Of the proposed cures, myself, I’d prefer Papa Hemingway’s formula:

If Jeeves’s remedy is the liquid equivalent of a rap on the knuckles, Ernest Hemingway’s is a karate chop to the kidneys. True to form, he christened it Death in the Afternoon. ‘Pour one jigger of absinthe into a Champagne glass. Add iced Champagne until it attains the proper opalescent milkiness,’ he instructs—and then, even more ominously: ‘Drink three to five of these slowly.’

Death in the Afternoon

This one might sound tempting in the wake of Christmas parties, when you’re feeling festively emboldened and actually have the component parts to hand. However, all but the steeliest are likely to take one look at the noxious brew and heave it straight down the sink. Still, the very act of mixing a Death in the Afternoon is guaranteed to perk you up a bit—if only because it reminds you that things could be an awful lot worse.

RTWT

25 Jun 2020

click on image for larger version.

11 Apr 2017

Tom Simon takes a pretty successful poke at Annie Proulx in the course of a lengthy attack on pretentious literary modernism. Yay, Papa Hemingway! Boo! Jimmy Joyce!

This mania for stylistic weirdness, enforced by the blocking troops of Modernist criticism, led in the end to a situation where even quite ordinary newspaper reviewers would shout praise for the ‘experimental’ brilliance of bad prose rather than admit to the nudity of the reigning monarch. One of the reigning monarchs of the nineties was Annie Proulx, who was extravagantly lauded for the following sentence in Accordion Crimes. A woman has just had her arms chopped off by sheet metal, and this is how Proulx describes it:

She stood there, amazed, rooted, seeing the grain of the wood of the barn clapboards, paint jawed away by sleet and driven sand, the unconcerned swallows darting and reappearing with insects clasped in their beaks looking like mustaches, the wind-ripped sky, the blank windows of the house, the old glass casting blue swirled reflections at her, the fountains of blood leaping from her stumped arms, even, in the first moment, hearing the wet thuds of her forearms against the barn and the bright sound of the metal striking.

Every story is a conversation between writer and reader, even though the writer is effectively deaf and seldom hears what the reader is saying. Here is a rough transcript of the conversation as it transpires in the passage above:—

Proulx. My character is stunned. Absolutely gobsmacked. Don’t I do a wonderful job of telling you how gobsmacked she is? She’s not just amazed, she’s rooted.

Reader. I don’t think that’s how people react to having their arms chopped off.

P. Now if I were one of these hack commercial writers, I’d talk about her. But see how cleverly I do everything by indirection! See how poetic I am! The barn is built of clapboards, you see—

R. I don’t care about the clapboards. This woman is bleeding to death!

P. And you can see the wood grain because the paint has all been worn off, but I wouldn’t put it that way, oh no, I’m a Writer, I am. So I said to myself, what’s a better action verb to use in this place? Why, chewed, of course! But that’s not poetic enough for me, because I’m a Special Snowflake, I am. So I changed it to jawed instead. Isn’t that original? Aren’t I clever? Look at meeee!

R. I don’t think that word means what you think it means. It doesn’t mean chew; it means to natter on endlessly, just like you’re doing now. Now will you stifle it and get on with the story?

P. Now I describe the swallows, and they’re so ironic, because they’re unconcerned, don’t you see? And they’re just carrying on about their business, darting out of sight and coming back—

R. All this while that poor woman’s arms are flying through the air? They must be miles away by now.

P. That’s not my point. My point is that they’re catching insects, don’t you see, and the insects are like moustaches! Isn’t that clever? Only a Writer could have come up with that simile! Look at meee!!

R. I think you’re mistaking me for someone who cares.

P. And then I describe the rest of the scene, and I’m just as clever about that, and the windows don’t just make reflections, they make swirled blue reflections, because I’m a Writer, I am, and look at me being all impressionist!

R. I think I’m going to skip on a bit.

P. Spoilsport! All right, I’ll get in a bit about my character, since you seem so anxious for me to be all boring and nasty and commercial and stick to the silly old point. What do you think I am, the six o’clock news? So her blood is spurting, no, that’s too ordinary, leaping from her stumped arms—

R. You mean from the stumps of her arms. ‘Stumped’ means something completely different. It has to do with not having a clue, hint, hint.

P. I’m a Writer, I am, and you can tell because I don’t let myself be limited by your silly old bourgeois rules. Her stumped arms, I said, and I’m sticking to it. And then she hears the wet thuds of her forearms—

R. Ewwww.

P. —against the barn, and then the sheet metal hits, and it’s not just the sound of it hitting, it’s the bright sound, because only a Writer would use something as nifty as synaesthesia to put her point across. See? I know about synaesthesia! I’m smart! Look at me! LOOK AT MEEEEEE!!!!

R. If you don’t get on with the story, I’m going to say the Eight Deadly Words.

P. (momentarily taken aback) Which are?

R. ‘I don’t care what happens to these people.’ I mean, if you’re going to stand there jawing (see, I used the word correctly) about swallows and moustaches and swirly blue windows, while the woman you have just mutilated is bleeding her life away — well, if you care as little as that about your own characters, I don’t see why I should give a damn. You haven’t even noticed that she’s in pain!

P. (angrily) This isn’t about her. This is about me! Me, meee, wonderful ME!! Damn you, why aren’t you looking at ME!!!

Of course this conversation is ruthlessly suppressed in the New York Times review by Walter Kendrick, who singled out that very sentence, in all its scarlet and purple excess, as ‘brilliant prose’. B. R. Myers was kinder to Proulx, if only in the interest of brevity:

The last thing Proulx wants is for you to start wondering whether someone with blood spurting from severed arms is going to stand rooted long enough to see more than one bird disappear, catch an insect, and reappear, or whether the whole scene is not in bad taste of the juvenile variety.

The sad truth, I am afraid, is that self-consciously ‘literary’ writers do not write to be read; they write to impress the critics, and if their ambitions are particularly lofty, to have their books made required reading for hapless English majors. Then the English majors, or a depressingly large percentage of them, buy into the pernicious notion that this self-regarding drivel really is ‘brilliant prose’ — and, still more, that brilliancy of prose is the primary and sufficient purpose of literature — and the whole sorry swindle is perpetuated for another generation.

Proulx’s star has more or less fallen since Myers launched his attack, but the sentence cult goes on.

RTWT

Hat tip to Karen L. Myers.

02 Apr 2017

Laidlaw’s tweet inspired others:

And still others:

More here.

Via The Passive Voice.

Hat tip to Karen L. Myers.

31 May 2016

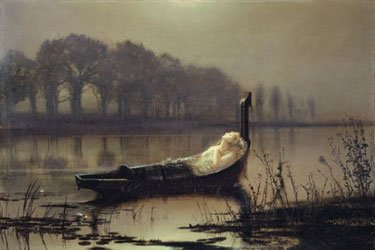

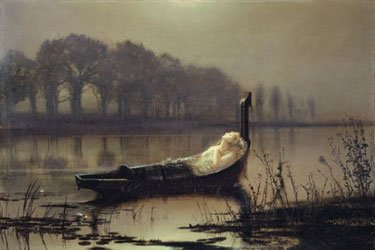

John Atkinson Grimshaw, The Lady of Shalott, 1875, Yale Center for British Art.

Cold hands

Beautiful face

Missing slippers

Wrist fevers

Night brain

Going outside at night in Italy

Shawl insufficiency

Too many pillows

Garden troubles

Someone said “No†very loudly while they were in the room

Letter-reading fits

Drawing-room anguish

Not enough pillows

Haven’t seen the sea in a long time

Too many novels

Pony exhaustion

Strolling congestion

Sherry served too cold

Ship infidelity

Spent more than a month in London after growing up in Yorkshire

Clergyman’s dropsy

Flirting headaches

River unhappiness

General bummers

Knitting needles too heavy

Mmmf

Beautiful chestnut hair

Spinal degeneration as a result of pride

Parents too happy

The Unpleasantness

From The Toast via Lucy Bellerby.

26 Jan 2016

Joseph Addison (1672-1719)

From Enemies of Promise, 1938 by Cyril Connolly:

Style is manifest in language. The vocabulary of a writer is his curency but it is a paper currency and its value depends on the mind and heart that backs it. The perfect use of language is that in which every word carries the meaning that it is intended to, no less and no more. In the verbal exchange Fleet Street is a kind of Bucket Shop which unloads words on the public for less than they are worth and in consequence the more honest literary bankers, who try to use their words to mean what they say, who are always ‘good for’ the expressions they employ, find their currency constantly depreciating. There was a time when this was not so, a moment in the history of language when words expressed what they meant and when it was impossible to write badly. This time I think was at the end of the seventeenth and the beginning of the eighteenth century, when the metaphysical conceits of the one were going out and before the classical tyranny of the other was established. To write badly at that time would involve a perversion of language , to write naturally was a certain way of writing well. Dryden, Rochester, Congreve, Swift, Gay, Defoe, belong to this period and some of its freshness is still found in the Lives of the Poets and in the letters of Gray and Walpole. It is a period which is ended by the work of two great Alterers, Addison and Pope.

Addison was responsible for many of the evils from which English prose has since suffered. He made prose artful, and whimsical, he made it sonorous when sonority was not needed, affected when it did not require affectation; he enjoined the essay on us so that countless small boys are at this moment busy setting down their views on Travel, the Great Man, Courage, Gardening, Capital Punishment to wind up with a quotation from Bacon. For though essay-writing was an occasional activity of Bacon, Walton and Evelyn, Addison turned it into an industry. He was the first to write for the entertainment of the middle classes, the new great power in the reign of Anne. He wrote as a gentleman (Sir Roger is the perfect gentleman), he emphasized his gentle irony, his gentle melancholy, his gentle inanity. He was the apologist for the New Bourgeoisie who writes playfully and apologetically about nothing, casting a smoke screen over its activities to make it seem harmless, genial and sensitive in its non-acquisitive moments; he anticipated Lamb and Emerson, Stevenson, Punch and the professional humorists, the delicious middlers, the fourth leaders, and the memoirs of cabinet ministers, the orations of business magnates, and of chiefs of police. He was the first Man of Letters. Addison had the misuse of an extensive vocabulary and so was able to invalidate a great number of words and expressions; the quality of his mind was inferior to the language which he used to express it.

18 Jun 2014

Ivan Aivazovsky and Ilya Repin, Pushkin’s Farewell to the Sea, 1877, All-Russian Pushkin Museum, Moscow.

Chapter list:

6. An Argument That Is Mostly In French

7. It’s Very Cold Out And Love Does Not Exist Also

8. The Nihilist Buffs His Fingernails While Society Crumbles

9. There Is No God

10. 400 Pages Of A Single Aristocratic Family’s Slow, Alcoholic Decline

Hat tip to Tristyn Bloom.

19 Dec 2010

David Ross was recently moved to re-read Atlas Shrugged.

In an experience shared by many, he found the novel much better, and far more worthy of respect as a work of literature, than he had remembered.

The Obama era was, for me as for so many others, an open invitation to reread Rand, so thoroughly does she seem to diagnose the psychology of our present slide into statism (Obama’s constant rhetoric about sibling-keeping might as well be plucked from the mouth of Wesley Mouch). News that Atlas Shrugged is finally being filmed also helped inch the book to the top of my pile. …

I was trepidacious, however, not sure to what extent I might have outgrown Rand. I was not concerned about the palatability of her philosophy, to which I have never specifically subscribed, but about her prose and her craftsmanship, which self-congratulatory journalist types constantly deride as second-rate, the kind of thing that only a teenager or cultist could fail to smirk at. This passing reference in a December article in the Weekly Standard is typical:

Atlas Shrugged, while a perennial bestseller and an important artifact of 20th-century culture, is not exactly great literature (stilted dialogue and cardboard characters have ranked among the defects pointed out by critics).

I have now reread the first half of Atlas Shrugged, and I can offer my very educated opinion that it is great literature, not necessarily at the sentence level, but in the unstoppable propulsion of its narrative (has a philosophical novel ever been so engrossing?), in the massive, dauntless sweep of its ideas, and in its enormous imaginative feat of creating a myth of our entire world (Dante and Milton are Rand’s compeers in this limited, formal respect).

Even more, Atlas Shrugged is a great work of literature in its comprehensive taxonomy of modern men, in its comprehension of all their hidden springs and insecurities and frustrations and ambitions. Rand fancied herself a political theorist and metaphysician, but she misunderstood herself; she was a psychologist foremost, and Atlas Shrugged is a formidable system of psychology to contraindicate that of Freud. Eschewing the usual bedroom and bathroom preoccupations, Rand grasps that behavior is driven by what she calls ideals, conscious or unconscious structures of value that provide the context for everything we do and everything we are. Freud tends to reduce these structures to underlying psychosexual dynamics, but Rand insists on their primacy and irreducibility, and she illustrates their role as the ceaseless motive forces of life. She is also a particularly shrewd diagnostician of a certain kind of resentment and leveling instinct – James Taggart is the obvious embodiment – and she is nearly alone in realizing that this mindset is no trivial phenomenon but the rotting core of our world, explaining everything from the Soviet world-blight to our failing schools and lousy art.

Rand’s characters are ‘cardboard’ in the sense that they speak for philosophical positions and represent certain types, but each character embodies something slightly different; there is no overlap or redundancy. In the aggregate, they form a spectrum of humanity – a human comedy – that is convincing and powerfully explanatory. Rand is accused of engaging in moral black and white, but this is not entirely fair; while her scheme is moral in logic and purpose, many of her characters – Dr. Stadler for example – represent subtle, equivocal positions. They are not gray, but an intricate admixture of black and white.

Rand sketches her characters in only a few clean strokes, but these strokes are rendered so deeply and forcefully as to be ineffaceable. Who can forget Hank Reardon or Dagny Taggart? Who can forget their triumphant inauguration of the John Galt Line? Who can forget their strange, violent lovemaking? What character drafted by Henry James, by contrast, does anything but deliquesce and drift imperceptibly from consciousness, becoming a vague haze of inflection and velleity?

Atlas Shrugged is a great novel, finally, in its astonishing originality. It has no precedent in terms of style, tone, mood, or philosophy, as far as I know. Victor Hugo may account for its sweep and social engagement, and someone like Zamyatin may have influenced its anti-totalitarianiasm and latent dystopianism, but nothing accounts for its strangeness, for everything powerfully eccentric and not infrequently repellent that Rand herself brings to it, everything rooted in the passionate kinks and quirks of her personality. In the end, it belongs in the category of the sui generis along with modern masterpieces like Ulysses, The Castle, and Pale Fire.

I suppose I would say that Atlas Shrugged needs to be viewed as a fantasy mystery story operating as an extended exercise in political argument and moral instruction, different from, but fundamentally akin to such non-realistic, and intrinsically polemical, works of literature as the Divine Comedy, Pilgrim’s Progress, Utopia, Hudibras, or Gulliver’s Travels.

Rand’s characters are not so much one-dimensional cardboard figures as they are what Erich Auerbach in Mimesis refers to as figura, characters serving as rhetorical illustrations of the operation of virtues, vices, and political ideas in social, business, and civic interaction. The wonder is not that Rand’s characters do not completely plausibly resemble ordinary real world human beings, but that her walking, talking illustrations of virtues, character flaws, rationality, and corrupting delusion are as successfully animated as they are.

Rand’s really conspicuous failures, far more than in characterization, lay in her Bohemian intellectual’s lack of understanding of the normal attitudes and perspectives of businessmen and her glaringly atrocious apprehension of the state and direction of technology. Ayn Rand living in the American 1950s sees the Count of Monte Cristo commuting to the office instead of the Organization Man. George Babbitt, in her mind, becomes transformed into Zarathustra. Rand is also disastrous as a prophet of the direction of business opportunities. One pictures her taking those whopping royalty checks and purchasing bundles of stock certificates in such cutting edge industries of the future as railroads, coal mines, and steel mills. Rand was oblivious to a post-industrial reality which was just around the corner. There are no data processing engineers, chip designers, or programmers in her cast of technologists. Hank Reardon has a lighter new metal alloy. John Galt is monkeying around with cosmic rays. Nobody is building personal computers, cell phones, or the Internet.

29 May 2010

Katherine Mansfield

Michelle Kerns, in the Telegraph, collects 50 colorful examples of abuse of fellow authors by well-known writers.

Pt. 1

Pt. 2

Examples:

William Faulkner, according to Ernest Hemingway

Have you ever heard of anyone who drank while he worked? You’re thinking of Faulkner. He does sometimes — and I can tell right in the middle of a page when he’s had his first one.

E.M. Forster’s Howards End, according to Katherine Mansfield (1915)

Putting my weakest books to the wall last night I came across a copy of ‘Howards End’ and had a look into it. Not good enough. E.M. Forster never gets any further than warming the teapot. He’s a rare fine hand at that. Feel this teapot. Is it not beautifully warm? Yes, but there ain’t going to be no tea.

And I can never be perfectly certain whether Helen was got with child by Leonard Bast or by his fatal forgotten umbrella. All things considered, I think it must have been the umbrella.

Hat tip to Walter Olson.

E.M. Forster

06 Oct 2009

As I’ve previously observed, a lot of people on both the political left and right neglected to consider some pretty obvious aspects and details of the liaison between Roman Polanski and a certain young lady 32 years ago and simply accepted her Grand Jury testimony uncritically as a perfectly factual and objective version of events.

That acceptance of a less than complete, biased and self-interested account, combined with a liberal application of emotionalism and indignation, easily turned a tawdry Hollywood casting couch trist into a horrid sex crime with a child victim. Left or right, a surprisingly large number of people seem to find the editorial equivalent of participation in a lynch mob to be a gratifying form of self expression.

The probation officer all those years ago was in possession of a more accurate and complete understanding of the case, and his sentencing report, quoted by the New York Times, arrives at very different conclusions.

The report, submitted by acting probation officer Kenneth F. Fare, and signed by a deputy, Irwin Gold, recommended that Mr. Polanski receive probation without jail time for his conviction on one count of having unlawful sex with a minor. In a summary paragraph, the report said: “Jail is not being recommended at the present time. The present offense appears to have been spontaneous and an exercise of poor judgement by the defendant.†It went on to note that the victim and her parent, as well as an examining psychiatrist, recommended against jail, while a second psychiatrist described the offense as neither “aggressive nor forceful.â€

Despite Ms. Geimer’s age and her testimony that she had objected to having sex with Mr. Polanski and asked to leave Jack Nicholson’s house, where the incident occurred, the probation report concluded, “There was some indication that circumstances were provocative, that there was some permissiveness by the mother,†and “that the victim was not only physically mature, but willing.â€

As we see, the authorities at the time, took the young lady’s testimony of her own reluctance with a very large grain of salt, doubtless concluding that both the circumstances of the encounter and many of her own actions signaled explicitly affirmative intentions.

The most interesting aspect of all of this is the fact that Roman Polanski’s flight thirty one years ago was precipitated by precisely the same sort of journalistic feeding frenzy which has been replayed all over again recently. A firestorm of sensationalized accounts of Polanski’s misdeed alarmed the publicity-conscious judge who intended to set aside the conventional processes of justice and overrule a plea bargain already agreed to by both the prosecution and the defense.

Polanski did not escape justice. He had already served a 42 day term of imprisonment, which was supposed to constitute his actual sentence. Polanski also settled privately with the young lady, paying her a sum of money of a specific amount never publicly disclosed. What Polanski escaped was injustice.

He escaped a breach of the normal, impartial, and objective processes of justice, which were in the process of collapsing due to official cowardice and unwillingness to resist a wave of public indignation, mischievously created by irresponsible journalism.

Long-standing cultural restraints on sexual expression and activity have been dwindling away in America for all of the last century, but one powerful prohibition not only survives, but continues to be able to turn ordinary Americans into something very much resembling belligerent Muslims bent on wiping out any stain upon the chastity of their females in blood: the issue of age.

Underage sex is still a kind of priapic third rail. And like Nabokov’s Humbert, Roman Polanski proved to be another sophisticated European gentilhomme d’un certain âge susceptible to the charms of the knowing nymphette. His sin happens to be relatively unique in being capable of getting Americans in general worked up into a lather of righteous indignation just as effectively in 2009 as in 1978 or in 1955 (the publication date of Lolita).

In exactly the same way that the idea of black sexual aggression directed at white women was once upon a time so horrifying an idea to the general community in certain American states that any close resemblance to that supreme phobia could suffice to set into motion the processes of storytelling which would fit the details of the actual case into the terrible archetype, frequently with lethal results, so too today is the idea of adult sexual aggression directed at children a compelling, and potentially dangerous, archetype.

Let’s try another literary trope. Picture Roman Polanski, not as Humbert Humbert, but as Tom Robinson, the black defendant in To Kill a Mockingbird. Just like the Polanski case, To Kill a Mockingbird features a public frenzy of indignation at a defendant accused of being a sexual aggressor toward an innocent victim, who is supposed to be protected from the advances of anyone like the defendant by powerful social taboos. Just as in the Harper Lee novel, adjudication of the Roman Polanski case revolved around issues of just who was the actual initiator and whether female consent had been given. Fearful archetypes and framing narratives can work in exactly the same in either case, can’t they?

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Literature' Category.

Feeds

|