Heidegger’s Ghosts

Anti-Rationalism, Anti-Westernism, Martin Heidegger

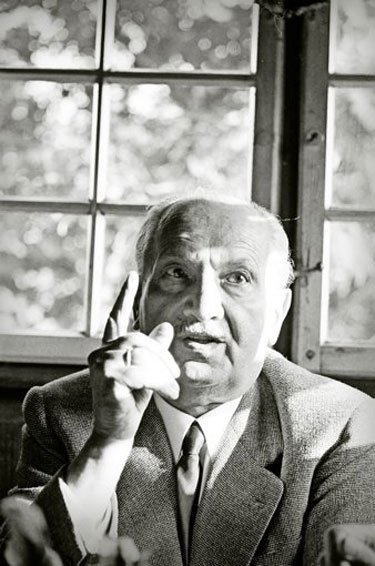

Martin Heidegger at his house in Todtnauberg, January 1966

Alexander Duff, in the American Interest, notes that every contemporary form of irrational opposition to Western Liberalism, Capitalism, and Democracy draws upon the intellectual influence of the Swabian sexton’s son, educated by the charity of the Church of Rome, who in the 1930s betrayed his Church and presided happily over the National Socialist Gleichschaltung (“bringing into conformity”) of his university.

A specter haunts the post-Cold War liberal order—the specter of radical spiritual malaise. This discontent with or downright opposition to the Western-originated, universalist claims of the broadly liberal cultural, economic, and political order takes diverse forms. One can detect it among Iranian revolutionary theocrats, Russian imperialist ideologues, white supremacist “Identitarians,†European neo-fascists, identity-politics partisans, and anti-foundationalist intellectuals of many stripes. But standing behind some of the leading intellectual and political figures in this mélange of counter-liberalism is one animating mind, that of Martin Heidegger.

Since the end of the Cold War, it has been an open question whether any organizing political principle could successfully vie with the liberal consensus of a secular state, limited by democratic accountability and the rule of law. To date, neither the remnants of Soviet-style communism, authoritarian capitalism, reactionary fascism, nor Islamic theocracy have achieved a successful combination of military strength and political legitimacy even among their own citizens, let alone among sympathizers in the world at large. But the political legacy of Martin Heidegger—if the strange and conflicting paths of his influence can be so termed—points to a combination that is sufficiently threatening to liberal democracy to be taken seriously, precisely because of the breadth of its evident appeal abroad and at home.

This is because Heidegger’s thought, while not lending itself to any politically cohesive opposition to the liberal West in a manner that characterized Marxism, recommends itself to virtually every variety of particularist opponent of Western universalism. For those inspired by Heidegger, the universalist claims upon which the liberal order is based are too thin, too weak, and too ignoble to provide tangible and meaningful sources of human identity.