Richard A. Warshak, in the Atlantic, associates the origin of the dark crimefighter with a boyhood beating experienced by his creator.

Years ago I became aware that a particular superhero, who has entertained millions of people, had special appeal to the traumatized children who visited my office. I had a hunch that a trauma had inspired the creation of this superhero. See if you think my hunch was correct.

His pals nicknamed him “Doodler†because he was constantly drawing pictures. His pals had nicknames, too—they were fellow members of a neighborhood club know as “The Zorros,†an appellation that a young Robert Kahn had chosen, inspired by the cinematic crusader for justice played by Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. The Zorros’ clubhouse was built with wood stolen from the neighborhood lumber yard—a place whose many nooks and crannies made it the location of choice for their games of hide-and-seek.

One night, when he was 15 years old, Kahn—who went by “Robbie†at the time—had a terrifying encounter. Walking home through rough neighborhoods of the Bronx after a music lesson, carrying a violin case, he was followed by “a group of seedy-looking roughnecks from the tough Hunts Point district,†as he wrote in his autobiography 57 years later:

They wore the sweatshirts of the Vultures, and they were known to be a treacherous gang. They were whistling at me and making snide remarks that only “goils†played with violins. I stepped up my pace and so did they. Finally, I started running and they did likewise, until I reached my neighborhood. Unfortunately, my buddies were not hanging around the block at the time.

Kahn’s memoir goes on to give a very lengthy, melodramatic blow-by-blow account of his dash to the familiar lumberyard, the Vultures’s pursuit (“with terrifying menace in their eyesâ€), and his attempts at self-defense, complete with “Zorro†leaps, grappling hook, and mid-air kicks while swinging on a rope. He fought bravely, he writes, but for naught:

My worst fears came true. Two Vultures pinned both my arms behind my back and held me firm while another beat a staccato rhythm on my belly, knocking the wind out of me. Another bully stepped in and used my face for a punching bag—while he cracked a couple of my front teeth.

I was in a fog, when I felt my right arm crack at the elbow after a gang member deliberately twisted it behind me in order to break it. The pain was excruciating and I screamed in agony.

Before I blacked out and fell to the ground like a limp rag doll, I heard him laugh sardonically, “Just to make sure dat da Fiddler ain’t gonna play his fiddle no more!†Little did he know that it wasn’t playing the violin again that concerned me, but the fact that he had broken my drawing arm.

Then he stepped on the hand of my broken arm! I don’t remember how long I remained in a blanket of darkness before I regained consciousness, but when I came to, I was a beaten, bloody wreck. Somehow I managed to pull myself up and it was then that I noticed my violin on the ground, smashed to pieces. This was the coup de grace!

This whole episode, to this day, remains in my subconscious like a nightmare. I had played Zorro and lost! Had it really been a dream or a movie, I would have emerged victorious. But this real-life drama had almost cost the life of a reckless fifteen-year-old.

Here we have a boy who was attacked by a gang of Vultures in the night. He defended himself by playing Zorro, using a grappling hook to fend off his attackers. He was unsuccessful and was hospitalized, severely injured, with the possibility that he would be unable to pursue his chosen career. In spite of permanent injuries—scars, chipped teeth, and limited mobility in one arm—he went on to become a cartoonist.

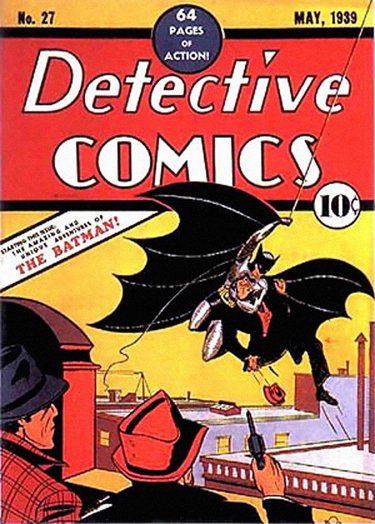

Seven years after being brutalized, he created a comic-book superhero that would become a pop-culture legend—and whose appeal may be deeply, subtly connected to what happened that night in the lumber yard.

Please Leave a Comment!