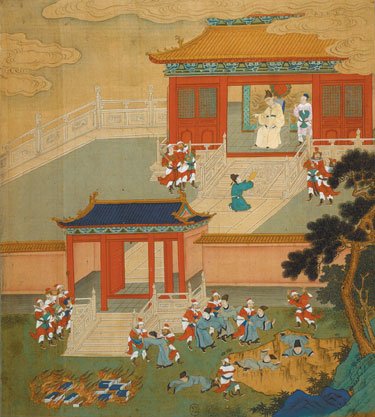

Emperor Ch’in Shih Huang Ti of the Ch’in dynasty ‘burning all the books and throwing scholars into a ravine’ in order to stamp out ideological nonconformity after the unification of China in 221 BC.

Ian Johnson reviews, in the New York Review of Books, Sarah Allan’s Buried Ideas: Legends of Abdication and Ideal Government in Early Chinese Bamboo-Slip Manuscripts, a study of ancient Chinese manuscripts written on bamboo slips containing the views of heretofore-unknown Ch’in-suppressed Chinese philosophic schools completely outside the familiar Confucian and Taoist traditions, views favoring meritocratic rather than hereditary dynastic government.

As Beijing prepared to host the 2008 Olympics, a small drama was unfolding in Hong Kong. Two years earlier, middlemen had come into possession of a batch of waterlogged manuscripts that had been unearthed by tomb robbers in south-central China. The documents had been smuggled to Hong Kong and were lying in a vault, waiting for a buyer.

Universities and museums around the Chinese world were interested but reluctant to buy. The documents were written on hundreds of strips of bamboo, about the size of chopsticks, that seemed to date from 2,500 years ago, a time of intense intellectual ferment that gave rise to China’s greatest schools of thought. But their authenticity was in doubt, as were the ethics of buying looted goods. Then, in July, an anonymous graduate of Tsinghua University stepped in, bought the soggy stack, and shipped it back to his alma mater in Beijing. …

The manuscripts’ importance stems from their particular antiquity. Carbon dating places their burial at about 300 BCE. This was the height of the Warring States Period, an era of turmoil that ran from the fifth to the third centuries BCE. During this time, the Hundred Schools of Thought arose, including Confucianism, which concerns hierarchical relationships and obligations in society; Daoism (or Taoism), and its search to unify with the primordial force called Dao (or Tao); Legalism, which advocated strict adherence to laws; and Mohism, and its egalitarian ideas of impartiality. These ideas underpinned Chinese society and politics for two thousand years, and even now are touted by the government of Xi Jinping as pillars of the one-party state.

The newly discovered texts challenge long-held certainties about this era. Chinese political thought as exemplified by Confucius allowed for meritocracy among officials, eventually leading to the famous examination system on which China’s imperial bureaucracy was founded. But the texts show that some philosophers believed that rulers should also be chosen on merit, not birth—radically different from the hereditary dynasties that came to dominate Chinese history. The texts also show a world in which magic and divination, even in the supposedly secular world of Confucius, played a much larger part than has been realized. And instead of an age in which sages neatly espoused discrete schools of philosophy, we now see a more fluid, dynamic world of vigorously competing views—the sort of robust exchange of ideas rarely prominent in subsequent eras.

These competing ideas were lost after China was unified in 221 BCE under the Qin, China’s first dynasty. In one of the most traumatic episodes from China’s past, the first Qin emperor tried to stamp out ideological nonconformity by burning books. … Modern historians question how many books really were burned. (More works probably were lost to imperial editing projects that recopied the bamboo texts onto newer technologies like silk and, later, paper in a newly standardized form of Chinese writing.) But the fact is that for over two millennia all our knowledge of China’s great philosophical schools was limited to texts revised after the Qin unification. Earlier versions and competing ideas were lost—until now.

Read the whole thing.

Hat tip to Belacqui.

Please Leave a Comment!