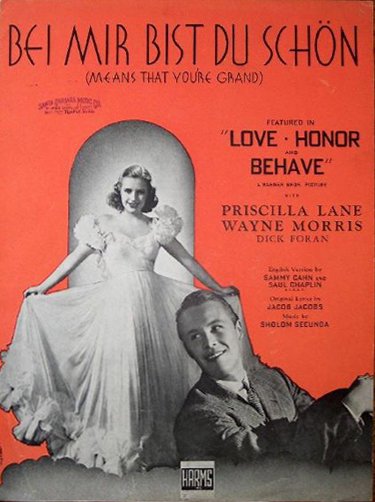

“Love, Honor and Behave” (1938)

"Love, Film Reviews, Hollywood, Honor and Behave" (1938), Yale

Karen and I recently had the opportunity to view on Turner Classic Movies a curious, low budget old movie, “Love, Honor and Behave” (1938), lacking entirely a memorable big name cast, but specifically focused on the subject of Yalie-ness, on the distinctive old-fashioned Yale ethos.

The plot.

The marriage of old-time Yale man Dan Painter (Thomas Mitchell) to the stately and quite attractive Sally Painter (Barbara O’Neil, best known for playing the role of Scarlett O’Hara’s mother in “Gone With the Wind”, one year later, at age 28!) breaks up over a brief indiscretion. Sally remarries Doctor MacConaghey, taking away Dan’s son, Ted Painter (Wayne Morris).

Sally insists on raising Ted, contrary to his father’s wishes, as the paradigmatic good loser. Losing gracefully and graciously is her idea of being a gentleman. She refuses to send Ted to Andover (Dan’s old preparatory school), enrolling him in a different (possibly fictional) preparatory school in New Haven which I’d never heard of, because she believes Andover would make him too manly, too ruthlessly aggressive, and competitive. She won’t even allow Ted to play football like his father, bringing him up instead to be a tennis player.

Ted, at least, is permitted by mom to go to Yale. During his son’s senior year, Dan Painter is horrified as he watches Ted, playing for Yale, deliberately throw a tennis match against a Harvard rival because he believes the referee had previously made an erroneous call in his favor. Dan believes you ought to play by the rules, but you have to play to win. Intentionally losing is decidedly not proper manly behavior, not the Yale way.

The unhappy consequences of Ted’s upbringing by his mother continue even after graduation. Ted does rebel against mom, refusing to go to Medical School (in order to follow in his stepfather’s footsteps), but instead getting into the soap business in New Rochelle with a classmate. Ted also marries his childhood sweetheart Barbara Blake (Priscilla Lane) contrary to mom’s intentions and designs. But mother’s character formation lessons in uncompetitive self-effacement and non-aggression take their inevitable toll. The soap business goes under, and Ted cannot make Barbara happy.

When Ted’s business fails, Dan refuses to give Ted a job in his own business on grounds of principle (Dan is not only a Yalie, he talks exactly like an Ayn Rand character), and Ted is reduced to settling for menial work as a construction laborer for $3 a day.

Having had his problems trying to make a living during the Depression, Ted has been too busy working to entertain Barbara satisfactorily. Since he’s not available to take her out, and too passive to lay down the law, Barbara begins stepping out on Ted with a former rival. Finally, the worm turns, the deep-blue hereditary Yale blood (even without Andover’s influence) boils over, and Ted initiates a knock-down, drag-out fight with Barbara, ending in his giving her a good spanking. He also rises to the occasion and knocks down his rival with a good punch in the nose, and then throws him physically out of the house.

Dan Painter (conveniently on-hand to see the whole thing) is absolutely delighted. He now knows that his son has learned his lesson: that a man has to fight for things in this world, for success in business, even for his woman, just as he needs to be determined to achieve victory in athletic contests. Ted is now a properly competitive Yale man, just like his father.

LHB is certainly not a great film, not even a good film, but it is extremely interesting as a period piece and a case of watermark evidence of national-level recognition of a specific culture and personality associated with Yale way back then.

I was at Yale 30 years later, much had changed in America and at Yale, but I would say that even 30 years later, the “no excuses, just succeed” ethos had definitely survived in a number of undergraduate organizations right up into my day.

By now, Dan Painter’s hearty and unabashed, manly competitiveness must be thickly encrusted with layers of political correctness grown all over it like barnacles but I wonder if the same thing in essence, today unglorified, unacknowledged and unavowed, does not yet still survive at dear old Yale.