Will Crutchfield on Maria Callas

Bel Canto, Maria Callas, Opera, Primo Ottocento, Sopranos

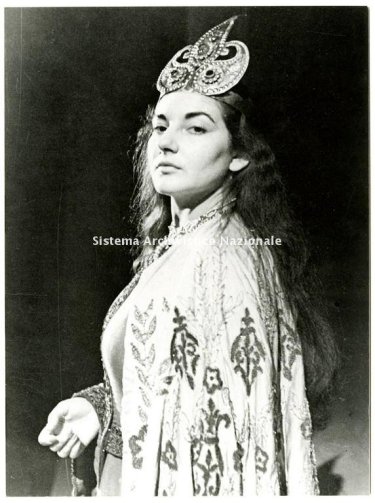

Maria Callas as Abigaille in Verdi’s Nabucco al Teatro San Carlo, Napoli 1949. (excerpt below)

In a genuinely brilliant 1995 New Yorker essay, musicologist Will Crutchfield describes her career and explicates why Maria Callas occupies an essentially unique position in the history of musical performance.

Callas performed vocal feats practically no soprano has equaled and single-handedly revived an entire operatic genre.

In the season of 1951-52, after triumphs up and down the peninsula, Callas established herself as prima donna at Milan’s La Scala, and made it her home theatre. For seven seasons, the house surrounded her with illustrious colleagues, conductors, directors, and designers, in revivals that were the news of the musical world. In familiar and unknown operas alike, Callas’s work almost always became the focus of the world’s thoughts about that role, and Callas herself became a celebrity. Then, in 1959, she went into sudden near-retirement, took up with Aristotle Onassis, and began the long professional and personal decline that still occasions deep regret and furious debate. Callas had been averaging fifty appearances a year; between her thirty-sixth and fortieth birthdays she sang in public only twenty-eight times. There was a flurry of troubled performances in 1964-65, and then silence until a disastrous concert tour in 1973-74.

Only one good decade, really. Callas’s entire stage career (excluding the Greek years) comprised just five hundred and thirty-nine performances. Enrico Caruso, who died at forty-eight, gave nearly two thousand. Chaliapin, one of the various singers who “invented” acting in opera before Callas “invented” it, made his début in 1890, and was still touring, recording, and singing gorgeously in 1937, just months before his death. The only other musician in this century to make anything like Callas’s impact in so few appearances was the Canadian pianist Glenn Gould. Both of them—like Chaliapin, Caruso, Arturo Toscanini, and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau—permanently changed the way their successors understood the music they were most closely associated with. But Callas brought this about largely by conservative means, through the affirmation of tradition. Gould and the others were revolutionaries; she never was. …

What Callas was helping to restore was once the most popular music in the world: the operatic repertory of Italy in the first half of the nineteenth century—the primo ottocento, as the Italians call it. This was the heady moment when Classical virtuosity, inherited from the brilliant vocal rhetoricians of the eighteenth century, coexisted with high Romanticism. The novels of Walter Scott, the poetry of Byron, the music of Beethoven: the younger Italian poets and composers took all these like drugs, and the operas they created swept back over Europe and the world. Callas’s core repertory came from this school, which reaches from the serious operas of Rossini (she sang one, “Armida”) through Bellini and Donizetti, to “Il Trovatore” and “La Traviata,” where Verdi, already striking out on new paths, drew for the last time on the full expressive vocabulary of his predecessors. Bellini’s Norma was Callas’s most frequent role, followed by Verdi’s Violetta and Donizetti’s Lucia; more than half her stage career was devoted to music composed in the narrow span from 1830 to 1853.With opera moving on in symphonic and naturalistic directions, the decline of the Classical bel-canto skills was inevitable, and by 1900 most of the great operas of the primo ottocento were forgotten. The few that remained in repertory tended to be treated as tired relics, or as surefire comedies and romances that would play themselves (in shamelessly cut and edited versions), while serious artistic effort was focussed elsewhere. Some of the light sopranos kept the bel-canto skills flickeringly alive. But there had been nothing like Callas’s alacrity and speed since about 1910, and what there had been then came with the haphazardness of a discipline no longer valued and slipping into disuse.

Callas had all the exactitude and purpose of a valiant restorer. She had mastered more fully than almost any of her Italian contemporaries the art of legato and portamento (“carrying” the voice smoothly from note to note), and she had an extraordinarily lambent projection, which allowed every word to tell without overpronunciation. Her concentrated focus of tone allowed every gradation of softness to carry through the hall, every minute manipulation of rhythm to register. In every role, on practically every page, there were phrases that Callas was able to trace with a calligrapher’s pen where audiences had become accustomed to a carpenter’s pencil.

—————————–