Forgetting Mahan

"The Influence of Sea Power Upon History", Alfred Thayer Mahan, China, Federal Budget, US Navy

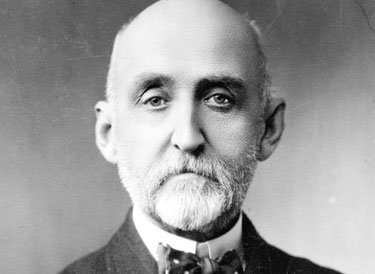

The Obama Administration is pursuing the characteristic democrat preference for dramatic reductions in defense expenditures which would seriously impact US Naval strength. Seth Cropsey and Arthur Milikh remind us of the intimate connection between American prosperity, commercial success, and world leadership and the philosophy of naval preeminence advocated in Alfred Thayer Mahan’s 1890 strategic study “The Influence of Sea Power Upon History: 1660-1783.”

The world’s waterways are of themselves neutral and without a preference for the state that governs them. Different states bring their own order of governing the seas, and the US brings with it liberal economics. It is difficult to imagine serious discussions of international maritime law, or treaties that establish a law of the seas, had the Soviet Union emerged victorious in the Cold War.

America’s allies in the Pacific are currently being pressed more immediately by the Chinese than we are. They see, as Americans tend not to, that the US is in a long-term competition with China, and recognize, as we don’t, that the Chinese desire slowly to push US sea power out of the international waters close to them. The only force standing in the way of such a transition, which would destroy a complex web of alliances for the US in the Pacific, is our current sea power.

Alfred Thayer Mahan offers the intellectual arguments that address what the US stands to lose economically and militarily—and all that China will gain—if there is a profound shift of power in the Western Pacific. Commerce, he believes, plays to the natural advantage of an enterprising people who are largely free to act upon their judgment and enterprising spirit. But commercial advantage and our enterprising spirit relies equally on the ability to keep open the oceanic arteries through which commerce must be able to flow. This equation is set on its head when prosperity becomes an important instrument to justify single-party rule—as in China, where freedoms of commerce are restricted by the state’s pressing requirement, for example, to employ millions; by an understanding of commercial freedom that is wholly separate from political freedom; and by a parallel view of sea power that sees the interruption of commerce as a personal threat to those who rule the state.

Mahan saw correctly that American greatness depends on dominant sea power. He understood the close connection between domestic prosperity and maritime preeminence. The acceptance of his ideas at the beginning of the twentieth century helped immeasurably in encouraging both, the condition of which is the only one in the memory of Americans alive today.