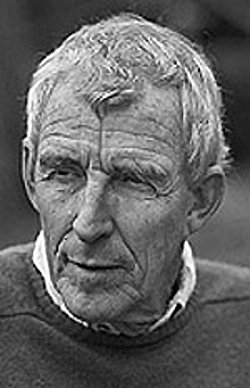

Peter Matthiessen (May 22, 1927 – April 5, 2014)

Jonathan Meiburg managed to get in a last interview with Peter Matthiessen shortly before his death from leukemia last April at age 86.

At first, the cab driver couldn’t find it; the empty fields to the left and the low trees to the right were covered in snow, and there was no looming Hamptons mansion at the end of the road. “I don’t think there’s anywhere else here,†he said. But then it appeared: a modest, low-slung house glimpsed through a tunnel in the trees. As we pulled into the drive, it was clear that Peter Matthiessen’s home for the last six decades wouldn’t be considered a normal home anywhere. An enormous skull—the cranium of a fin whale—was braced against a wall of the house, and clusters of other artifacts rested half-buried in the snow: driftwood, stumps, shells, small boulders, sculptures. I rang the doorbell and no one answered, and for a moment it was completely quiet: rain dripped off a row of icicles hanging from the roof. And then a kindly, deeply lined face peered through the glare in a pane of the front door.

What to say about Peter Matthiessen? There was no one quite like him: a writer and thinker, a naturalist and activist, and a fifty-year student of Zen Buddhism who, as his publicist put it, “lived so large, and so wild, for so long.†He was the only person ever to win the National Book Award for both fiction (Shadow Country, 2008) and nonfiction (The Snow Leopard, 1979), along with a bushel of medals and prizes for his elegant but unsentimental books (of which there are at least thirty), most of which concern the wild places, animals, and people “on the edge,†as he said, of the farthest parts of the globe, where pre-human landscapes and premodern pasts are (or were) still visible.

These edges are, more or less, where he spent his adult life. A précis of his travels is a bewildering list, and includes the Himalayas, the islands of the South Pacific and the Caribbean, the Mongolian steppe, Africa from the Serengeti to the Congo basin, South America from the Andes to the Amazon, the boreal forests of North America and Siberia, and a “musk ox island in the Bering Seaâ€â€”and that’s far from exhaustive. These travels would be remarkable enough, but he also cofounded the Paris Review, in 1953 (while working undercover for the nascent CIA); a few years later he was a struggling novelist and commercial fisherman using nets and dories off Long Island’s South Shore. …

Above all, Matthiessen followed his own muse, and though he avoided repeating himself, all of his books combine his searching, acerbic intelligence with his gift for evoking landscapes and people, and all are shot through with glimpses of a reality beyond human understanding—a bit like what Werner Herzog calls “ecstatic truth.†It’s a marriage of the dignified and the avant that can make his writing seem, at times, like a really good translation from another language. Both nature writing and what’s now called creative nonfiction owe him a huge debt, though his pure fiction tends to be overlooked (Far Tortuga, the experimental novel that preceded The Snow Leopard, doesn’t get the notice it deserves). …

Inside his house, everything was orderly, earth-toned, and wooden, both genteel and rough-hewn. Photographs of the people of the New Guinean highlands he visited in 1961 (vividly recalled in Under the Mountain Wall: A Chronicle of Two Seasons in Stone Age New Guinea), some of them taken by expedition mate Michael Rockefeller, surrounded a weathered baby grand piano; a pair of binoculars rested on its back on the piano’s lid. Smooth river stones, one of them incised with an elongated face that might be the Buddha’s, lined the sills of tall windows, among potted maidenhair ferns and a blooming Christmas cactus. In the backyard, two wooly-coated deer flecked with ice craned their necks to suck bird seed from a feeder, displacing a little cloud of cardinals and white-throated sparrows.

We sat in a cramped spare room he was using as a study, since the small outbuilding where he’d done the bulk of his writing was losing a battle with mold. He took a swivel chair beside the computer where he was working on yet another book: a memoir. It was a form he regarded with suspicion, and he was still finding its structure, which he compared to the branching leaves of giant kelp. I had to place my recorder close to him to catch his deep, conspiratorial rasp, but there was plenty it didn’t capture: he talked with his face and his hands as much as his voice, widening his eyes in surprise or crinkling them in mirth, fluttering his fingers to dismiss the encrustations of “lush writing†or opening his palms in surrender to a great line of prose. Or he enlisted all his features in sudden imitations of people or animals: an Inupiat pilot swatting a mosquito, a grizzly bear recoiling at the sight of a human, a white shark trying to swallow an outboard motor. The landscape of his creased forehead, wild eyebrows, and silver hair suggested stormy weather, but his eyes were a surprisingly mild, even innocent, blue. Only a month before his death, at the age of eighty-six, he was still clearly the man from the jacket flap of The Snow Leopard, and his memory for the smallest details of books he wrote half a century ago was ironclad. The pad of his right thumb was stained with green ink.

A great interview moment:

PM: My great question, I would say, comes from Turgenev, from Virgin Soil. One of the characters kills himself, but he leaves a note, and the note says: “I could not simplify myself.†[Drops jaw] Boy, that’s like that Akhmatova line, the epigraph from In Paradise—

BLVR: “Something not known to anyone at all—â€

PM: “—but wild in our breast for centuries.†Yes, you know. Oh! [Groans as if smacked in the chest] I know that feeling so well. It’s been my great, great aim in life, simplification. Total failure.

Read the whole thing.

Please Leave a Comment!