Atlas Obscura recounts Steve Libert’s search for Le Griffon, the first European ship to sail the waters of the upper Great Lakes, lost more than 300 years ago.

Since its disappearance in 1679, the Griffon has taken on a mythic air. Widely considered the Holy Grail of undiscovered Great Lakes shipwrecks, the Griffon carried no treasure, nor anything else that may have retained its value after several centuries underwater. All the wreck offers is a brush with history—and the chance for its discoverer to link their name with that of a legendary explorer.

Shipwreck hunters joke that the Griffon is the most searched for and the most found ship in the Great Lakes—meaning there have been countless false alarms. Wayne Lusardi, a maritime archaeologist for the state of Michigan, has investigated at least 17 Griffon claims since 2002. Only two were actual ships. “I’ve looked at telephone poles, pieces of people’s barns that have washed up on the beach, piles of rocks, things like that,†Lusardi says.

Each new claim inspires a flurry of breathless headlines, but decades of dead ends have made the local shipwreck community wary. So far, the doubters have been right every time. The state’s official position is that no evidence of the Griffon has been found to date.

The cold, fresh water of the Great Lakes is kind to shipwrecks, and the 337-year-old wreckage could theoretically be found almost entirely intact. Each year, the lakes’ eerily preserved wrecks attract thousands of divers, tourists, researchers, and history buffs. Of those, only an elite handful are dead-set on finding the Griffon, but everyone knows the story.

Like any good ghost ship, the tale is steeped in fame, fortune, and intrigue. For the explorer Robert de La Salle (full name: René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle), who staked his wealth and reputation on the ship’s cargo, the disappearance was part of a chain of misfortunes that would eventually claim his life.

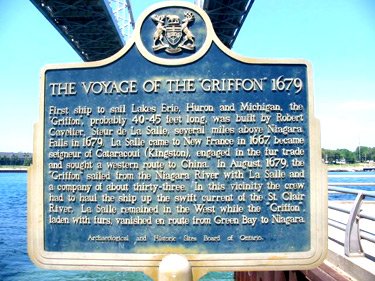

On January 26, 1679, Robert de La Salle drove the first bolt into the keel of what would become the Griffon, a barque longue of 30-50 feet. He planned to sail to the western shores of Lake Michigan, where he would hopefully collect enough furs to assuage his debtors while establishing a French presence in the region.

The Griffon set sail from Niagara on August 7 of that year. The crew launched earlier than planned to avert sabotage, then faced a hard slog through the shallow St. Clair River and a near-fatal storm on Lake Huron. Despite all this, La Salle arrived at the mouth of Green Bay almost a month after his initial departure: September 2, 1679. Some of his men had gone ahead via canoe to barter for furs, and awaited him onshore. Sixteen days later, the Griffon re-embarked for Niagara without La Salle aboard.

What happened next is lost to history.

La Salle continued exploring the continent’s interior, but the Griffon was never far from his mind. He began to worry about the ship’s safety after months passed without word from his crew. Neighboring tribes reported seeing the boat sail into a violent storm, then finding a hatch cover, spoiled pelts, and other apparent wreckage the following spring.

La Salle would eventually come to believe something more sinister. In a letter from 1683, he reported hearing strange rumors: A nearby village had been visited by a neighboring tribe. They had brought captive Frenchmen carrying pelts and explosives—both of which the Griffon had been carrying. One of the men may have matched the description of the ship’s pilot, a man most records refer to as Luc the Dane. Luc, La Salle decided, must have sabotaged the ship to sell the furs himself.

Until his death in 1687, La Salle believed his crew had betrayed him.

It was three hand-hewn pegs in the beam that first made Libert suspect he’d finally solved one of the biggest mysteries of the Great Lakes. Given the wood’s shape, apparent age, and location, he concluded the beam was the Griffon’s bowsprit, used to maneuver the sails. And so he returned year after year.

Please Leave a Comment!