Lauren Elkin, in Aeon, pays tribute to the late Susan Sontag’s “monstrous” appetites for thinking, culture and the arts, and living la vie de la Bohême.”

There are things it has taken me two decades as a serious reader and writer to become aware of or to articulate, things that Sontag noticed straight off the bat in Against Interpretation, at the age of 33. Skimming her essays today, I’m struck by the sharpness of their insights and the breadth of their references. Dismayingly, nearly 20 years after I first read her, I still have not caught up to Sontag, and neither has our critical culture.

You won’t find Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche, Hume or György Lukács nonchalantly dotting the page in criticism today; it is supposed that readers aren’t up for it. But Sontag charges in and dares to distinguish between their good and mediocre work. She isn’t afraid of Jean-Paul Sartre. Writing on his book on Jean Genet, she notes: ‘In Genet, Sartre has found his ideal subject. To be sure, he has drowned in him.’ She stood up to men held up as moral giants. Albert Camus, George Orwell, James Baldwin? Excellent essayists, but overrated as novelists. In 1966, Sontag checked an America that was in thrall to realism and normative morality, demonstrating how to respond to the ‘seers, spiritual adventurers, and social pariahs’ as she put it in her essay on the French dramatist Antonin Artaud.

Her special brand of monstrous relentlessness saw her go in search of paradox. Moderation, and those who practised it, never interested her. It seemed to her like a cop-out. And she believed that only the immoderate rose to the level of the culture-hero: people who took things to extremes, who were ‘repetitive, obsessive, and impolite, who impress by force’, as she wrote of the French philosopher Simone Weil. Sane writers are the least interesting writers, and Sontag had that stripe of insanity, like that grey thatch of hair, that made you sit up and listen, and also made you a little nervous. Her pungent public personality won her a reputation for being, as Sigrid Nunez put it in 2011, ‘a monster of arrogance and inconsideration’. She was a monster – for art. She read everything, watched everything, listened to everything, went to see everything. How did she fit it all in? It’s as if she lived several lives in one. She sat in the middle of the third row at the cinema, so that the image would overwhelm her. She would not, could not, relax. Art was too important. Life was too important.

Look across her many books: she simply does not let up. Every sentence is a new challenge; there is no filler. I’ve lost track of how many times I’ve read On Photography (1977), and every time it’s like I’m reading a new book. There’s something very constructed and Germanic about her sentences; I find myself reading her cubistly, not left to right only but also up and down, piecing together what she’s saying chunk by chunk instead of line by line. She quotes very infrequently, and is less interested in local textual moments than in building up a global reading of an author’s work. She frequently revised her opinions, so no sooner have I got a handle on On Photography than she’s off on another tack in Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), further refining it in ‘Photography: a Little Summa’ (2003). She was uninterested in boiling down her views to an easily citable argument; she resisted simplification in every aspect of her life and work.

‘Boring, like servile, was one of her favourite words,’ writes Nunez in Sempre Susan (2011), recalling her time as Sontag’s assistant and her son David’s girlfriend. ‘Another was exemplary. Also, serious.’ The word ‘serious’ and its variants (‘seriousness’, ‘seriously’) appear 120 times in Against Interpretation, a text of 322 pages. That’s every 2.6 pages. For Sontag, seriousness was an all-encompassing, even physical way of being in the world. ‘Yet so far as we love seriousness, as well as life, we are moved by it, nourished by it,’ she wrote in her essay on Weil. ‘In the respect we pay to such lives, we acknowledge the presence of mystery in the world – and mystery is just what the secure possession of the truth, an objective truth, denies.’ Mystery is missing from all that is sage, appropriate, nice, fitting, obedient. Notice Sontag’s emotive, personal choice of words: we are moved by seriousness; it affects her (and, she presumes, her reader) on a primary, physical level.

This is what her detractors so often miss in her work. ‘Mind as Passion’ she called her essay on Canetti. Style. Will. Mind. Passion. These are also words that recur throughout her work. She wasn’t just serious: she was passionate about the mind and its possibilities. The mind, to Sontag, was a feeling organ.

I read Against Interpretation during high school, in the 1960s, back in my provincial Pennsylvania small town where films by Bresson and Godard were never shown.

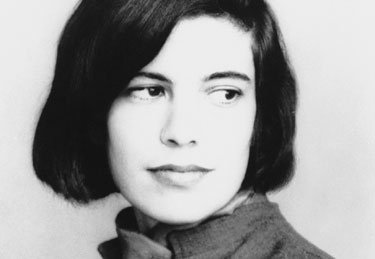

I was already very much on the opposite side of the Culture Wars, but Sontag’s brilliant, deep readings of the cutting edge products and doings of the opposite camp made for fascinating reading. I could not resist falling in love with her intelligence and passionate engagement. I actually traced the cover photo (above) in pencil, and produced a drawing of Sontag of my own and hung it on my wall.

I met her, by accident, years later, and we talked at length, and thereby actually became friendly regular acquaintances. I ran into her frequently at major cultural events in New York in the late 1970s and early ’80s. We always saluted each other, and we sometimes sat together and exchanged comments during a performance. I saw several films in her company at the Bleeker Street Cinema, having run into her by accident. Karen and I sat with her and Lillian Gish during the NYC premiere of the restored print of Abel Gance’s Napoleon (1927), and a merry time was had by all. During the intermission, Sontag introduced us to Steven Spielberg and Gary Lucas with whom she was seeing Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s Parsifal (1982) at Lincoln Center.

She was certainly the greatest critic of contemporary arts and culture generally of her time. Despite her limitless ambition, she was clearly much less successful as a novelist and director. Her taste and capacity to distinguish and appreciate excellence in the work of others was unsurpassed, but she could not do everything at the same level of excellence. Who can?

I would say that her opinions, life, and work were somewhat adversely affected by the inevitable influence upon a passionate young girl of her ethnicity and background of the culture of her time. But, then, as I’ve previously noted, I am myself a perennial critic and opponent of precisely that culture.

Nonethless, despite her born membership of the Left and her admiration for, and association with, the subculture of Perversity, I still liked and admired her personally. And I do still read her with pleasure.

She was guilty of a couple of very unfortunate political statements and, like all the rest of the community of fashion, she was wrong on Vietnam and wrong on pretty much everything politically, but still, in the early ’80s, she condemned a number of Communist atrocities and seemed teetering, for a while, on the edge of breaking with the Left. I won’t tell you the whole story now, but I know that it could have happened.

gwbnyc

the revolving homage. mandatory reference-

Plath

Sexton

Sontag

-on the cyber quarter hour, for eternity.

Please Leave a Comment!