The colorful secret of a 1,600-year-old Roman chalice at the British Museum is the key to a superÂsensitive new technology that might help diagnose human disease or pinpoint biohazards at security checkpoints.

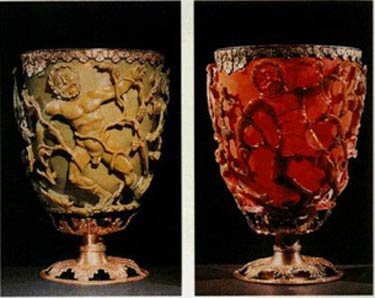

The glass chalice, known as the Lycurgus Cup because it bears a scene involving King Lycurgus of Thrace, appears jade green when lit from the front but blood-red when lit from behind—a property that puzzled scientists for decades after the museum acquired the cup in the 1950s. The mystery wasn’t solved until 1990, when researchers in England scrutinized broken fragments under a microscope and discovered that the Roman artisans were nanotechnology pioneers: They’d impregnated the glass with particles of silver and gold, ground down until they were as small as 50 nanometers in diameter, less than one-thousandth the size of a grain of table salt. The exact mixture of the precious metals suggests the Romans knew what they were doing—“an amazing feat,†says one of the researchers, archaeologist Ian Freestone of University College London.

The ancient nanotech works something like this: When hit with light, electrons belonging to the metal flecks vibrate in ways that alter the color depending on the observer’s position. Gang Logan Liu, an engineer at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, who has long focused on using nanotechnology to diagnose disease, and his colleagues realized that this effect offered untapped potential. “The Romans knew how to make and use nanoparticles for beautiful art,†Liu says. “We wanted to see if this could have scientific applications.â€

When various fluids filled the cup, Liu suspected, they would change how the vibrating electrons in the glass interacted, and thus the color. (Today’s home pregnancy tests exploit a separate nano-based phenomenon to turn a white line pink.)

———————–

The cup’s history via Wikipedia:

The cup was “perhaps made in Alexandria” or Rome in about 290-325 AD, and measures 16.5 x 13.2 cm. From its excellent condition it is probable that, like several other luxury Roman objects, it has always been preserved above ground; most often such objects ended up in the relatively secure environment of a church treasury. Alternatively it might, like several other cage cups, have been recovered from a sarcophagus. The present gilt-bronze rim and foot were added in about 1800, suggesting it was one of the many objects taken from church treasuries during the period of the French Revolution and French Revolutionary Wars. The foot continues the theme of the cup with open-work vine leaves, and the rim has leaf forms that lengthen and shorten to match the scenes in glass. In 1958 the foot was removed by British Museum conservators, and not rejoined to the cup until 1973. There may well have been earlier mounts.

The early history of the cup is unknown, and it is first mentioned in print in 1845, when a French writer said he had seen it “some years ago, in the hands of M. Dubois”. This is probably shortly before it was acquired by the Rothschild family. Certainly Lionel de Rothschild owned it by 1862, when he lent it to an exhibition at what is now the V&A Museum, after which it virtually fell from scholarly view until 1950. In 1958 Victor, Lord Rothschild sold it to the British Museum for £20,000… .The cup is normally on display, lit from behind, in Room 50 (it forms part of the museum’s Department of Prehistory and Europe).

Please Leave a Comment!