Category Archive '“A Christmas Carol”'

22 Dec 2016

—————————-

—————————-

Hat tip to Lee Liberman Otis.

14 Dec 2016

Tom Mullen argues that Dickens and Hollywood got everything wrong about Scrooge.

As Butler Shaffer demonstrated in his brilliant defense of poor Ebenezer, Scrooge was an invaluable benefactor to English society before the events of Dickens’ story. We are not given details of his business dealings other than they had something to do with finance. That Scrooge had been in business so many years and had amassed such wealth is enough for us to conclude he had made many more wise decisions on where to direct capital than unwise ones.

Who knows what housing, stores, railways or other benefits to society Scrooge had made possible through his wise judgment? How many thousands of jobs had he created? Dickens is unjustly silent on this. Whatever Scrooge had financed, we know it was something the public wanted or needed enough to pay for voluntarily. Thanks to Scrooge, however crusty his demeanor, the common people of London were far richer than they otherwise would have been without his services.

His only weakness seems to be sentimentality towards the whiny, presumably mediocre-at-best Bob Cratchett. We know Scrooge was paying Cratchett more than anyone else was willing to or Cratchett would surely have accepted a higher-paying job to put additional funds towards curing Tiny Tim. But we really don’t have any evidence anyone else was willing to employ Cratchett at all, at any salary level. Still, we must defer to Scrooge’s judgment on this and perhaps even laud him for finding a way to employ a substandard employee without jeopardizing the firm as a whole.

Thus, all was as well as it could have been on December 23. Scrooge’s customers were happy, Bob Cratchett was at least employed, thanks to Scrooge, and Scrooge himself was as happy as he could be, considering the ingratitude with which his genius had been rewarded and all the panhandlers constantly shaking him down.

Everything changed on Christmas Eve, when Scrooge was terrorized – there really is no other word for it – by three time-traveling, left-wing apparitions. It wasn’t enough to frighten an elderly man with the mere appearance of ghosts. They took him on a trip through time, scolding him for supposed mistakes made in the past and blaming him for the misfortunes of others in the present and future. And let’s not forget the purpose of this psychological waterboarding. They are not, as Shaffer observes, pursuing Scrooge’s happiness, but his money. They are William Graham Sumner’s A & B conspiring to force C to relieve the suffering of X. Politicians A & B use the polite coercion of legislation; the spirits make use of more direct and honest threats of violence.

Their plot was successful. Scrooge awoke from his night of terror obviously out of his senses and began making one poor financial decision after another. Perhaps buying the largest turkey in the local shop could be excused on Christmas Day. But then, without any evidence of improvement in performance, he raised Bob Cratchett’s salary and promised to take on the Cratchett family’s medical expenses.

After that, we are told Scrooge was “transformed†completely, which we can only interpret to mean he no longer made the kind of decisions that had previously benefited so many. We are told Scrooge’s subsequent behavior was so foolhardy that some people laughed at him. But even this wasn’t enough to snap him out of the permanent delirium with which the spirits had inflicted him.

How many profitable ventures were never financed, both before and after Scrooge went out of business?

The story ends on that foreboding note. We are told Scrooge never again returned to the prudent decision-making that had brought on the supernatural terror attack on Christmas Eve. We have to assume the “transformed†Scrooge eventually went out of business, perhaps solely due to overpaying Cratchett, who is 50% of his labor force, perhaps due to the cumulative effect of the many unwise decisions we are told continued afterwards.

Not only was Tiny Tim’s medical care cut off, but the whole Cratchett family was rendered destitute and starving. As Scrooge had already been paying Cratchett more than anyone else was willing to, even before the imprudent raise, we have to assume Cratchett made less after Scrooge went out of business than he did at the beginning of the story, if he convinced anyone to employ him at all.

Worse even than the misfortune that befell Scrooge, Cratchett and Tiny Tim was the misfortune visited upon society as a whole. How many profitable ventures were never financed, both before and after Scrooge went out of business from investing with his heart instead of his head? How many future jobs were destroyed and children of unemployed fathers left sick and hungry?

23 Dec 2014

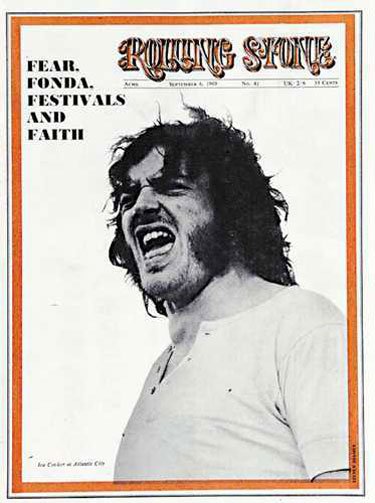

Joe Cocker, Rolling Stone 41, September 6, 1969

Sippi has updated the Dickens classis.

Cocker was dead: to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the barman, the A&R weasel, Google analytics, and the chief mourner. Rolling Stone signed it: and Rolling Stone’s name was as good as a contract with Alan B. Klein, for anything he chose to put his hand to. Old Cocker was as dead as a door-nail.

Read the whole thing.

—————————-

Hat tip to Vanderleun.

23 Dec 2011

E. Scrooge, CEO of Scrooge & Marley, LLC with his ne’er-do-well nephew Fred.

Jim Lacy, at National Review On-Line, has a spirited defense of one of the first of the 1%-ers.

I contend that Scrooge, before he became “enlightened,†was already doing more to help his fellow man than any of the other main characters we meet in A Christmas Carol. Moreover, by giving away a substantial portion of his accumulated fortune, he drastically reduced his ability to do even more good in the world.

Scrooge was a “man of business†and evidently a shrewd and successful one. Although Dickens fails to tell us exactly what line of business Scrooge is in, a typical 19th-century “man of business†could be expected to involve himself in many endeavors — what investment advisers today refer to as diversifying one’s risk. One can infer from A Christmas Carol that Scrooge was a financier, who lent money to both businesses and individuals. He also spent long hours at the Exchange, probably speculating on commodities, buying and selling government debt, and purchasing and selling shares in various joint stock companies.

We can also infer some things about Scrooge that Dickens does not tell us directly. He left boarding school early, supposedly because his father had a change of heart toward him and wanted him home. A lack of finances may also have had something to do with it, as Scrooge’s formal education ended early and he was apprenticed as a low-level clerk to a tradesman — Mr. Fezziwig. From this low start, Scrooge exhibited a relentless drive that eventually made him rich. Along the way, his business had to survive the Napoleonic Wars, adapt to the Industrial Revolution, and fight its way through several severe economic depressions. In fact, in the year A Christmas Carol was written (1843), Britain was just coming out of a five-year economic slowdown in which only the most nimble and carefully managed enterprises survived. During Scrooge’s business life, upwards of 100 businesses failed for every one that succeeded. Scrooge must have been a very good businessman indeed.

There is no hint that, as Scrooge went about making his fortune, he was ever tainted with any scandal. He appears to be a well-respected, if not overly liked, member of the Exchange. This speaks well for his probity and recommends him as man with a reputation for fair and honest dealing with other businessmen. He probably drove a hard bargain, but that is the nature of business, and his firm’s survival as a going concern depended on it. As Scrooge is trying to keep his doors open in the midst of a great economic downturn, one should not be surprised that he is cutting firm expenses by reducing coal usage. Still, he is not being overly stingy by paying his clerk, Bob Cratchit, 15 shillings a week. According to British Historical Statistics, 15 shillings a week was about the average for a clerk at the time, and nearly double what a general laborer earned. While Cratchit may have to skimp to make ends meet, he is paid enough to own a house and provide for a rather large family. Cratchit is not rich, but by the standards of the time he is doing well. Besides, given the hard economic times, he is lucky to have any job at all. If Scrooge had not been careful with his money, his firm would have folded, and then where would Cratchit be? We may of course also infer something about Cratchit that goes unstated in Dickens’s work. His inability over perhaps two decades to advance himself or secure a better position with a more benevolent boss betrays a singular lack of ambition on his part.

Read the whole thing.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the '“A Christmas Carol”' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|