Category Archive 'Biography'

28 May 2017

No major writer’s works more explicitly express everything frowned upon today than Ernest Hemingway’s. Hemingway’s obsession with masculinity, stoicism, and competence; his fascination with war and with violence; his personal enthusiasm for blood sports like hunting, fishing, and bull fighting; his consistently flaunted masculinity and frank contempt for male homosexuality inevitably make Ernest Hemingway the important writer of the last century most offensive to everything sacred to today’s politically correct sensibility. Despite all of which, he continues to be read, he remains an important cultural icon, and the biographies keep on coming.

The petulant (then left-wing) poof Auden once complained of the ability of literary quality to overcome ideological propriety.

Time that is intolerant

Of the brave and the innocent,

And indifferent in a week

To a beautiful physique,

Worships language and forgives

Everyone by whom it lives;

Pardons cowardice, conceit,

Lays its honours at their feet.

Time that with this strange excuse

Pardoned Kipling and his views,

And will pardon Paul Claudel,

Pardons him for writing well.

Paul Hendrickson, six years ago, did a really excellent study of Ernest Hemingway’s personal decline-and-fall, “Amid So Much Ruin, Still the Beauty,†taking Papa’s fishing boat, the Pilar, as a kind of metonymyic symbol for the final 27 years and three months of the author’s life.

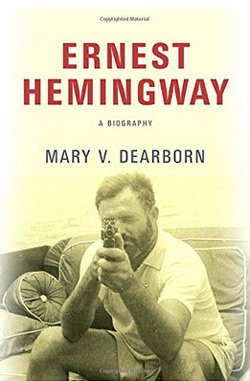

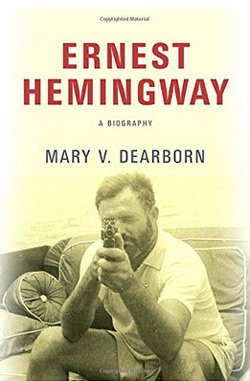

Mary V. Dearborn, previous biographer of Norman Mailer, Henry Miller, and Peggy Guggenheim, just published another new full-scale Hemingway bio. I am currently reading and enjoying it. Who would have imagined that a female author would, in this day and age, treat the old scapegrace so sympathetically.

You can tell that she is going to do a fine job, just by looking at her choice of cover photo.

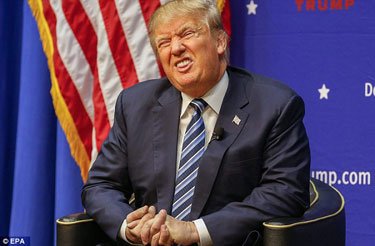

30 Apr 2016

Politico thought it would be good if everyone actually understood the reality of Donald Trump, so they convened some experts on Trump’s career and biography, five Trumpologists who covered him professionally: Wayne Barrett, a longtime Village Voice reporter; Gwenda Blair, a bestselling author; Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Michael D’Antonio; Harry Hurt III, an author and videographer; and Timothy L. O’Brien, a writer and editor at Bloomberg.

Three Excerpts:

1:

Michael Kruse: I’d like to start talking about Donald by talking about Fred Sr. and going back to the very beginning, to Jamaica Estates [the Queens neighborhood where Donald grew up]. What do people need to know? What should we know about Donald because of his father, because of that relationship?

Harry Hurt III: I ran into Fred at Coney Island, with his secretary-mistress, one day, and he usually went to a place called Gargiulo’s down in that area. But that was closed that day, and so I was with my researcher and we tailed them over to the original Nathan’s hot dog stand. Donald was flying somewhere at the time, and we overheard Fred wipe some mustard off his lip, like this here, and he said, “I hope his plane crashes.†And I looked at my researcher, and I said, “Did you hear what I just heard?†He said, “Yes, I did.†I said, “Well, that’s my man. That’s Fred. The apple don’t fall far from the tree.â€

2:

Barrett: Well, you know, with all this Tea Party anger that he’s appealing to now, he was the original bailout. I mean, the banks could have put him under any day. They took tremendous losses in those negotiations and deals. So they saved him. He was too big to fail.

Hurt: He was the original “too big to fail.â€

Barrett: He’s the consummate example of what his voters rail against.

O’Brien: I remember Trump’s finance chief Steve Bollenbach, who worked through the debt for him, said he had this conversation one day where they were going to take the yacht. And they didn’t want to take the yacht. And the light suddenly went on in their heads: The banks actually don’t want to control all these assets. They want him to operate out of it, and they both thought, “Wow.†That was the moment when they realized they had leverage.

You know, everything he does now, he doesn’t need loans to do any of it. The golf courses are owned by the members. They pay fees that finance it. He gets a salary from NBC from The Apprentice, and he gets licensing fees for everything else. I mean, there’s some projects, like the Chicago hotel—he got bank debt for that. Deutsche Bank loaned into that one.

Barrett: But he’s gone from the 18th floor to the 18th hole.

[Laughter.]

Blair: It was branding. It was the early branding that kicked in for him. He spent the ’80s getting that brand going. So he buys the shuttle, he buys the yacht, he buys the Plaza Hotel, everything—

O’Brien: The Generals.

Blair: The New Jersey Generals, which gets him onto the sports pages, which gets him up to a national level. So the branding he had in place, so by the time the first bankruptcy comes up, the brand is the thing they don’t want to let go of. They don’t want to foreclose and not have the name, which is so counterintuitive that the mind boggles. Like, wait a minute. This guy is in corporate bankruptcy, but his name—but that’s how it was. He could get the over-the-barrel piece for the banks, and he’s been doing it ever since. It’s the over-the-barrel piece which he did with the Republican Party now. How do you get them so they can’t get rid of you, they can’t let you go? And he’s really good at that.

Barrett: Well, the thing was that the banks wouldn’t complain, either. When they cut the deal with him, if they didn’t go on to a prosecutor—I mean, all of the financials that he gave the banks were totally false.

Hurt: And they’re liable for that, for not doing their due diligence.

Barrett: Yes. They were so embarrassed that they never went to a prosecutor. Clearly, there could have been a case made.

3:

O’Brien: The other thing, too, that I think the media has to hold his feet to the fire on is he’s gotten away with this notion that he’s a superior deal-maker, and a very successful businessman. I thought about it after he went after the Iran deal. He said, “Obama negotiated this horrible deal with Iran. It’s a bad deal, and when I get to Washington, there won’t be bad deals anymore. I’m a great deal-maker.†And then the reality, the objective reality, is that he’s been a horrible deal-maker. His career is littered with bad deals. And yet, he’s essentially now a human shingle. He’s not someone who’s a particularly adept deal-maker, if you look at his whole career.

Kruse: A human shingle, because there were the bad deals that brought him down in the early to mid-’90s, right?

O’Brien: What he was left with was licensing his name. So he licenses his name on mattresses and underwear and vodka and buildings, among other products.

Kruse: He made this transition from being an actual businessman, a person who does deals, some of which were good, to a grand promoter of his own name.

O’Brien: And the reality TV version of a successful businessman.

Barrett: This is the ultimate promotion of his own name. This is the ultimate brand.

Kruse: But the fact is that there is a middle ground. There is, basically, 1990-ish to 1995 where he is a failure.

O’Brien: He’s in desperate straits. He almost had to go personally bankrupt.

Kruse: The success is that he didn’t die a business death. The success was survival.

O’Brien: And he was a survivor, to his credit. He survived.

Kruse: Why, though, wasn’t that failure?

O’Brien: Because of The Apprentice. I think singularly because of The Apprentice. But he was a joke in between 1993 and 2003.

Blair: You know that family legacy, that family culture of “never give up.†He never said he was a failure. Everybody else said, “This guy is going down. He’s filed for bankruptcy. This is terrible,†but he didn’t say that. He continued to say he was the best of the best, the biggest of the biggest, and he went on. I think that’s a huge piece of that.

Barrett: I tell the tale towards the end of the book about after the settlement with Ivana, he goes to meet with John Scanlon, who was a New York publicist of some skill, and tries to hire Ivana’s publicist to now represent him, and tells John, who is now dead, “I’m going to make a giant comeback, and I want to be on the cover of Time again, and I want you to handle it.â€

So he’s already thinking that way, in that very down moment of his life, but he knew he had bilked the banks. The banks put him back up on the pedestal. They didn’t have to, but it took a while to climb up that ladder.

D’Antonio: What about the fact that Fred died and that money became available?

O’Brien: Which totally insulated him from a lot of problems, that inheritance that he got from Fred. At one point, he needed his siblings to extend him a loan. I think it was the hard reality of family money.

D’Antonio: The first thing I think that you credit him with is this creation of himself, which is very American, this idea that I’m going to imagine what I’m going to be, I’m going to tell the world that I’m it before I am it, and then the world is going to help me become it. And he did it.

O’Brien: Think about the genesis of The Apprentice. The show got launched because Mark Burnett [the producer of The Apprentice], as an immigrant to the United States, is selling blue jeans in Venice, California, barely making it. He doesn’t have any faith in himself and reads this book called The Art of the Deal, and he thinks, “Wow, this is the bible of how you make it in America.†And then whatever it is, 25, 30 years later, he does Survivor. That’s a huge hit. He becomes a force in the TV industry, and he thinks, “I’m going to go back to the godfather of my success, Donald Trump, and I’m going to create a TV show that embodies the inspiration I felt from The Art of the Deal.†And that’s how The Apprentice gets launched, because The Art of the Deal, as Wayne knows, didn’t comport with reality, and The Apprentice is just a TV version of The Art of the Deal. It’s a total distortion of reality.

Glasser: So it’s a TV show about a book about a guy who was an invented character.

O’Brien: Yes.

Glasser: That’s now led to a campaign based on the TV show based on the book.

O’Brien: About a man who’s saying he’s a politician, who could probably never really deliver on everything he’s saying.

D’Antonio: So it’s all about this autobiography, which isn’t auto, and it isn’t a biography—which is, you know, only in America.

Read the whole thing.

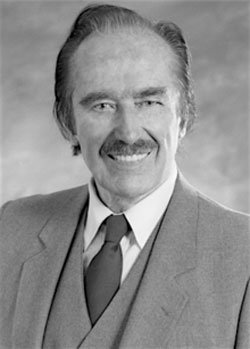

11 Apr 2016

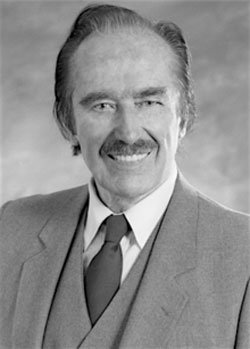

Fred Trump (1905-1999). Put another 50 lbs. on him, dye his hair blonde, dye his skin orange, give him a comb-over, remove the vest and put him in a dark blue suit with a necktie tied too long, and you have Donald.

Trump biographer Michael D’Antonio identifies the male influences, including his father, who trained Donald Trump in his “Law of the Jungle” philosophy and convinced him that bullying works and only success matters.

[F]or those of us who have followed Trump’s career from the start, the worldview he has trotted out to the public is no surprise. Some people seem shocked that he embraces torture without compunction; openly admires the suppression of freedom by Chinese and Russian dictators; and shows little grasp of ethics, governance or constitutionalism, as evidenced by his insistence that the U.S. openly engage in war crimes (by killing the families of terrorists). Or that he often seems ignorant of history and the economic benefits of free trade, dismissing the U.S. alliance and trading system that won the Cold War as “obsolete,†calling regularly for punitive tariffs and insisting over and over again, “We never win anymore,†as if trade were a zero-sum game (which it is not). Or that he relishes the idea that people at his rallies punch each other, suggesting that his supporters “knock the crap out of†any disrupters.

But, as Trump’s biographer, I can tell you these views fundamentally define the man. And if you’re looking—or perhaps hoping—for something more, you shouldn’t expect to find it. If you are seeking reassurance that the man who could be the next president of the United States possesses a coherent political philosophy or ethical foundation other than this rather pre-Enlightenment code of behavior—that he subscribes to the ideals of the Founders, or has studied and understood American democracy, human rights and our Constitutional system—you won’t get it.

Rare if not unique in American politics, Trump’s views and provocations are consistent with his biography.

Quite a story here. When you read this, you realize that Donald Trump is really a character right out of an old-time Harold Robbins novel.

10 Jul 2013

Maria Krystyna Janina Skarbek, GM, OBE, Croix de guerre aka Christine Granville

Clare Mulley’s The Spy Who Loved, previously published in Britain, has just been released in the US. It is the biography of Christine Granville, née Maria Krzystina Skarbek, a Polish aristocrat who became one of the most daring and successful British secret agents of WWII. According to Wikipedia, Christine Granville may have been the model for Ian Fleming’s Vesper Lynd.

Emma Garman reviews it with appropriate admiration in the Book Beast:

[While] traveling in South Africa [and she] heard the news that Germany had invaded Poland, Christine harbored not the tiniest qualm about leaving… in a rush to defend her beloved homeland. Presenting herself to British Intelligence in London—“a flaming Polish patriot … expert skier and great adventuress,†according to their records—Christine volunteered to ski into Nazi-occupied Poland armed with British propaganda. Her fervent aim, writes Mulley, was “to bolster the Polish spirit of resistance at a time when many Poles believed they had been abandoned to their fate.â€

That mission, carried out with a Polish Olympic skier turned mountain courier, set the tone for Christine’s career in its sheer wildness. Heading out from Czechoslovakia during the coldest winter in living memory, with snow four meters deep, the pair traversed the 2,000-meter-high Tatra Mountains, seeing two dead bodies on their way and later hearing that, on the night they reached the border, more than 30 people had died in the mountains trying to escape Poland. Then, once on a Warsaw-bound train, Christine’s nerve did not desert her: realizing that armed guards were doing spot checks of passengers’ possessions, she directed the beam of her preternaturally bewitching allure onto a uniformed Gestapo officer. Would he mind, she wondered, carrying the package of black-market tea that she was bringing her mother? He happily obliged, and so her sheaf of illicit documents—which, if discovered, would have led to merciless interrogation followed by the firing squad—reached their destination.

Such boldfaced aplomb would be deployed time and time again in dealing with the Nazis. When working for SOE (Special Operations Executive, the secret wartime sabotage unit) in the Alps, where she trekked between the French and Italian sides and transmitted vital information about enemy activity, Christine was stopped by the German frontier patrol. In her hand she held a silk map of the region, given to agents to avoid the giveaway rustle of paper in pockets. With no hope of concealing it, she casually shook the fabric out and used it to replace the headscarf she was wearing, greeting the soldiers in French as if she were simply a local on an errand. Another time she and Andrzej Kowerski, her on-off lover and frequent partner in crime, were arrested and interrogated by Gestapo officers in Budapest. Christine had been suffering from flu, so she exaggerated her hacking cough and bit her tongue so hard that she appeared to be bringing up blood. Presumed to be infected with tuberculosis—potentially fatal and frighteningly infectious—she and Kowerski were released.

Christine’s most jaw-dropping act of heroism would occur in August 1944: with a bounty on her head and her face having graced “Wanted Dead or Alive†posters, she strolled into a Gestapo-controlled French prison and, posing as another woman entirely, secured an interview with a corruptible gendarme. Every iota of her charm and resourcefulness coming into play, Christine successfully arranged to break out three colleagues—including her lover du jour, the 29-year-old Belgian-British agent Francis Cammaerts—who were about to be executed. “Good reading,†an SOE officer wrote on the cover note of Cammaerts’ subsequent report, “I am going to make sure that I keep on Christine’s side in future.†“So am I,†another scribbled in reply. “She frightens me to death.â€

—————————————————–

2012 review from the Spectator by Alistair Horne, titled “Bravest of the Brave:”

Of all the women agents who risked their lives in Nazi-occupied Europe in the second world war, Polish-born Krystyna must surely rate as one of the bravest of the brave. As they used to say in army vernacular, the George Medal (which was about as close to a VC as a foreign national could get), the OBE and the Croix de Guerre did not exactly ‘come up with the rations’.

Churchill is alleged to have rated Skarbek his ‘favourite spy’. The reason? In spring 1941 she passed minute details to London of Hitler’s plans for Barbarossa, the invasion of Russia. Churchill forwarded them on to Stalin, who promptly binned them.

Krystyna’s father was from the lesser Polish aristocracy, but her mother was Jewish (she was eventually swallowed up by the Holocaust) — a fact that would have made Krystyna’s repeated journeys under the noses of the Gestapo infinitely more dangerous.

Six times she trekked and skied across the Tatras, ‘exfiltrating’ high-risk Polish refugees into neutral Hungary, accompanied by her one-legged, long-term lover, Andrzej Kowerski (aka Andrew Kennedy). Seldom conducting an operation without a lover (proof of the 007 notion that sex and extreme peril often make for inseparable bed-mates), Krystyna’s reckless exploits smacked more of the age of Baroness d’Orczy than of the vile century of Heinrich Himmler.

Several of the witnesses in Clare Mulley’s scintillating and moving book, such as the late Paddy Leigh Fermor, testify to the fact that Krystyna did indeed thrive, quite irrationally, on danger. With her ‘fierce, almost blind pride,’ she reminded one British officer of the Polish cavalry that had charged Nazi Panzers in 1939. Arrested in Hungary, on one occasion she bit her tongue so hard as to draw blood, persuading the interrogators that she had TB. They released her.

Krystyna’s most legendary exploit came in summer 1944, in southern France, pending the Allied invasion. Her British boss (and also, naturally, lover), Francis Cammaerts (DSO, Croix de Guerre, Légion d’Honneur), one of SOE’s top operatives, had fallen into a trap and was awaiting imminent execution. She located his cell by humming ‘Frankie and Johnny’. Cammaerts responded by singing the refrain. Then Krystyna presented herself boldly to the milice officer holding Cammaerts, as a British agent—and a niece of General Montgomery, no less — sent to obtain the release of the prisoners. The invasion, she persuaded Cammaert’s captors, was but hours away and terrible reprisals would be exacted if the prisoners were killed. Coupled with Krystyna’s devastating charm, the ruse worked. All three agents walked free.

Maria Skarbek’s Polish coat of arms

01 Jul 2013

William Faulkner

Tim Parks, in the Bedwetters’ Review of Books, tries connecting some writers’ careers and characteristic themes with the manner and occasion of their deaths.

I expect it would have been too easy to discuss poor old Papa Hemingway and his 12 gauge Boss, but he did offer an amusing take on old Bill Faulkner.

[L]et’s consider William Faulkner.

Throughout his life, when asked for biographical details Faulkner would begin by saying he was the great grandson of the Old Colonel, a man renowned for his courage, temper, energy, and vision. And a writer to boot. In contrast Faulkner saw his own father as a nobody and a loser, an opinion he seemed to share with his mother, to whom he remained close throughout his life, having coffee with her most afternoons and never missing a family Christmas if he could help it. From his earliest days he was eager to present himself as bold and courageous, inventing in 1918 a bizarre story of having crashed a warplane while celebrating the end of the war. For years he affected a limp supposedly resulting from the crash, though at the time he had never piloted a plane at all. His brother was actually wounded in the war. Faulkner’s first novel focuses on a soldier returning home a hero, but so badly wounded that he dies.

Like Thomas Hardy, Faulkner eventually invented a fictional territory of his own where his novels could all take place in relation to each other. Acts of courage in Yoknapatawpha County—usually a very physical, manly courage, but also the courage to claim the woman you really desire—end up, as in Hardy’s novels, in wounds, disaster, and death. Like Hardy, Faulkner married a woman he was eager to betray but never able to walk out on. Community in the South is presented as a tremendous insuperable burden that one can neither escape nor overcome. The only freedom available is the freedom, the courage, to live slightly apart, not to engage, with the world or women, like Ike McCaslin, hero of The Bear.

Over the years Faulkner’s writing became both a solution to and a representation of the conflicting impulses that tormented him. His stylistic experimentalism became an act of courage in itself, allowing him to criticize the genuinely war-wounded and mythically courageous Hemingway for lacking the fortitude to write courageously, or to risk failure. Yet Faulkner’s experimentation is never liberating: his prose gives us the impression of a wild, would-be heroic energy pushing through an impossibly dense medium, shoving aside negative after negative to reach the brief respite of a positive verb, losing itself in a heavy slime of ancestors and ancient wrongs. It is not a world in which one could hope to become the courageous man Faulkner wished to be. From the black community, Faulkner told a friend, we can learn “resignation.â€

One major difference between the patterns that guide Hardy’s and Faulkner’s writing is the latter’s relationship with alcohol, which, more than a mere disinhibitor making courage possible, becomes a sort of courage in itself. However adventurous and ferociously provocative, his writing was not enough to satisfy Faulkner’s need to feel courageous. Throughout his life he drank epically, heroically. In the hunting camp that is the setting of The Bear we hear that

the bottle was always present, so that after a while it seemed to him that those fierce instants of heart and brain and courage and wiliness and speed were concentrated and distilled into that brown liquor which not women, not boys and children, but only hunters drank, drinking not of the blood they had spilled but some condensation of the wild immortal spirit, drinking it moderately, humbly even, not with the pagan’s base hope of acquiring the virtues of cunning and strength and speed, but in salute to them.

Whisky and writing intertwine throughout Faulkner’s life, feeding each other, blocking each other, never allowing him to achieve any stability, always acting out a salute to other men he feared he could not resemble. By the time he was fifty the end seemed inevitable. There are only so many times one can dry out in a clinic and fall drunk off a horse. It was actually something of a miracle that Faulkner outlived his dear mother for a year before one more courageous binge, one more salute to the truly brave, as he saw it, did him in, aged sixty-five.

Feeds

|