Category Archive 'British Library'

23 Oct 2020

Liz Jolly, Chief Librarian of the British Library since 2018.

David Warren is perfectly justified in ranting about all this.

Did you know? That, “Racism is the creation of white people�

Of course you did, if you are young, woke, and poorly educated, like the white woman who is now the British Library’s Chief Librarian. (“Liz Jolly.â€) Her statement, in a video to staff last summer, promoting her Decolonizing Working Group, though perfectly acceptable to Guardian subscribers, was mocked by several African and Asiatic scholars who have depended upon that library’s resources over the years. Noting that history is more complicated than Ms Jolly was ever told, they criticized her as “pig ignorant,†&c.

But her explicitly racist “anti-racist†programme proceeds, with aggressive “anti-racist†exhibitions, new “anti-racist†signage, and so forth. The demand to de-acquisition authors who do not reinforce the current ideological stereotypes has not yet gathered to full force, but has started.

The capture of essentially all major cultural institutions by unhinged political fanatics with daddy issues, is among the signs of our times. Those who resist are driven out of employment; those who accede have a lock on the splendidly-paid positions, for which beleaguered taxpayers are billed. The consequences to Western Civ are not trifling.

Perhaps I am unfair to single out just the one career arts bureaucrat, when there are thousands to choose from. I may even be prejudiced, not only against white people, but against those of the scheduled races who have cooperated in trashing the institutional heritage of the Big Wen.

For London was my Athens, back in the day, and I take these things personally. My British Museum Library ticket was among my most cherished possessions, and the old Reading Room among my favourite haunts. I am now so old that I can remember when such places were ruled, and staffed, by respectably boring establishment types with Oxbridge degrees.

Yet this is the very class that has suborned itself to the Revolution. It still works on old boy and girl networks, and has become dramatically more smug. But now it dismantles what its ancestors built. The fish-rot starts at the head of British society, as it has in Canada, and throughout America and Europe.

HT: Vanderleun.

12 Nov 2018

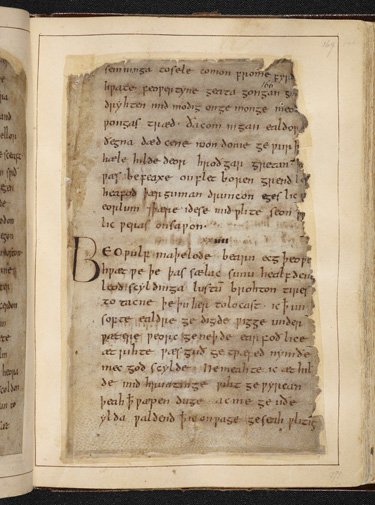

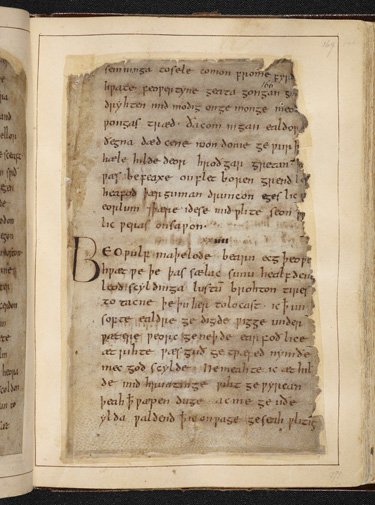

A page from Cotton Vitellius A. xv containing the epic poem Beowulf.

Josephine Livingstone got to see the four manuscripts of Old English poetry exhibited currently at the British Library. It would be nice to be in London right now.

There are four original manuscripts containing poetry in Old English—the now-defunct language of the medieval Anglo-Saxons—that have survived to the present day. No more, no less. They are: the Vercelli Book, which contains six poems, including the hallucinatory “Dream of the Roodâ€; the Junius Manuscript, which comprises four long religious poems; the Exeter Book, crammed with riddles and elegies; and the Beowulf Manuscript, whose name says it all. There is no way of knowing how many more poetic codices (the special term for these books) might have existed once upon a time, but have since been destroyed.

Until last week, I had seen two of these manuscripts in person and turned the pages of one. But then I visited “Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War,†a new show of artifacts at the British Library in London. It’s a vast exhibition, covering the art, literature, and history of the people whose kingdoms spread across Britain between the sixth and the eleventh centuries. The impetus for the show came from the library’s 2012 acquisition of the St Cuthbert Gospel, the “earliest intact European book,†in the words of the show’s catalog.

Seeing the earliest European book alone would be the event of a lifetime, for a certain kind of museum-goer. But for this viewer, the main attraction lay in a quiet little vitrine: all four Old English poetic codices, side by side. They don’t look that impressive to the casual eye. The exhibition room is dark and cold, to keep the books safe from damage. The manuscripts are brown, small, almost self-effacing. There’s no outward sign of how important they are, how unprecedented their meeting.

So why are these four books so special? It has to do, I think, with the concept of the original—a concept we have almost entirely lost touch with. The Beowulf Manuscript is not just composed of words that serve as the basis for every translation of the epic poem. It’s foremost an object, the only one of its kind. It is not merely a representation of a story; it is the story. In this respect, the manuscript resembles the Crown Jewels more than any document written in today’s world, any word that moves through the crazy fractal of the internet. The manuscripts confront us with a former version of our literary selves; identities that we barely recognize, and which estrange us from ourselves.

Each of the poetic codices has a specific history engraved into the text’s physical form. The very space they occupy on earth is meaningful. The Vercelli Book is named for Vercelli, a town in Northern Italy whose cathedral library holds the manuscript. Nobody knows for sure how the book got there, although the prevailing theory is that a pilgrim left it behind or gave it away on his travels. Who? Why? When? Unknown.

The Beowulf Manuscript’s permanent home is the British Library. Unlike Vercelli, we know exactly why it’s there. The manuscript’s pages have been remounted onto new ones, because the book was singed around the edges in a library fire in 1731. The fire consumed much of the collection of Robert Cotton—his unburned books were later all given to the British Museum, forming its foundational collection—but Beowulf only suffered a little. (The original Cotton collection was kept, with a horrible kind of accuracy, in a building called Ashburnham House.)

If we compare the Vercelli Book to the Beowulf Manuscript, we see different kinds of mysteries. The Vercelli Book is in fabulous condition, its English lines neatly written and sitting, inexplicably, in a region of Italy famous for its rice. The Beowulf Manuscript is a half-burned thing whose survival is a miracle. Its provenance is unknown: It was probably written down in the tenth or eleventh centuries, but it’s impossible to tell when it was actually composed.

RTWT

30 Jan 2010

ArtInfo:

At a whopping six-by-three feet (.9 x 1.9 m) (when closed), the Klencke Atlas, the world’s largest book (as opposed to the longest, which the Internet says is a Chinese encyclopedia in 11,000-plus volumes), will be making its first public appearance with its pages open this spring as part of an exhibition of maps at the British Library.

Though huge, the Atlas contains only 37 (very, very large) maps on 39 sheets, which depict the continents and assorted European states as engraved by Blaen Hondius and others. The book is said to have been a gift from Dutch merchant Yohannes Klencke to Charles II upon his restoration to the throne of England in 1660 (no word on whether Klencke also provided the world’s largest bookshelf to store the thing). The book was later gifted to the British Museum by King George III in 1828 as part of a larger collection of topographical materials.

Hat tip to Karen L. Myers.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'British Library' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|