Language, Culture, and Equality

Daniel L. Everett, Language, Noam Chomsky, Pirahã, Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

The Chronicle of Higher Education discusses the potentially revolutionary impact on Linguistics of Daniel L. Everett’s new book Language: The Cultural Tool.

Everett’s study of the Pirahã language offers evidence directly contradicting Noam Chomsky’s regnant belief in a Universal Grammar and taking linguistics back to the thoroughly out-of-fashion Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis which contended that language created the categories by which cognition classifies the world.

Chomsky’s view of linguistics, known as Universal Grammar,… has dominated the field for a half-century.

[Daniel Everett] believes that the structure of language doesn’t spring from the mind but is instead largely formed by culture, and he points to the Amazonian tribe he studied for 30 years as evidence. It’s not that Everett thinks our brains don’t play a role—they obviously do. But he argues that just because we are capable of language does not mean it is necessarily prewired. As he writes in his book: “The discovery that humans are better at building human houses than porpoises tells us nothing about whether the architecture of human houses is innate.”

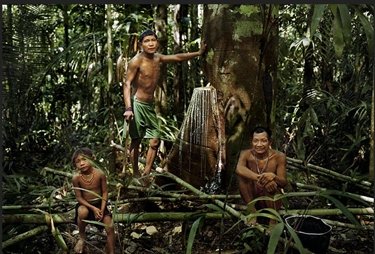

The language Everett has focused on, Pirahã, is spoken by just a few hundred members of a hunter-gatherer tribe in a remote part of Brazil. Everett got to know the Pirahã in the late 1970s as an American missionary. With his wife and kids, he lived among them for months at a time, learning their language from scratch. He would point to objects and ask their names. He would transcribe words that sounded identical to his ears but had completely different meanings. His progress was maddeningly slow, and he had to deal with the many challenges of jungle living. His story of taking his family, by boat, to get treatment for severe malaria is an epic in itself.

His initial goal was to translate the Bible. He got his Ph.D. in linguistics along the way and, in 1984, spent a year studying at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in an office near Chomsky’s. He was a true-blue Chomskyan then, so much so that his kids grew up thinking Chomsky was more saint than professor. “All they ever heard about was how great Chomsky was,” he says. He was a linguist with a dual focus: studying the Pirahã language and trying to save the Pirahã from hell. The second part, he found, was tough because the Pirahã are rooted in the present. They don’t discuss the future or the distant past. They don’t have a belief in gods or an afterlife. And they have a strong cultural resistance to the influence of outsiders, dubbing all non-Pirahã “crooked heads.” They responded to Everett’s evangelism with indifference or ridicule.

As he puts it now, the Pirahã weren’t lost, and therefore they had no interest in being saved. They are a happy people. Living in the present has been an excellent strategy, and their lack of faith in the divine has not hindered them. Everett came to convert them, but over many years found that his own belief in God had melted away.

So did his belief in Chomsky, albeit for different reasons. The Pirahã language is remarkable in many respects. Entire conversations can be whistled, making it easier to communicate in the jungle while hunting. Also, the Pirahã don’t use numbers. They have words for amounts, like a lot or a little, but nothing for five or one hundred. Most significantly, for Everett’s argument, he says their language lacks what linguists call “recursion”—that is, the Pirahã don’t embed phrases in other phrases. They instead speak only in short, simple sentences.

Beyond mere linguistics, the differences in the two theories have powerful implications overflowing into the moral and political question of equality. If certain peoples perceive and understand the world in fundamentally different ways, it is possible that their language and entire culture may not be equal to our own. Their language and culture may fundamentally limit their capabilities, and Imperialism may actually be morally obligatory.