Category Archive 'Language'

02 Mar 2024

“During this burn, several engines began shutting down before one engine failed energetically, quickly cascading to a rapid unscheduled disassembly of the booster,” SpaceX said.

HT: Arstechnica.com via Karen L. Myers.

20 Dec 2022

The Wall Street Journal marvels, like the rest of us, at how the most elite educational institutions have fallen into the hands of utter nincompoops and morons deranged by contemptible, crack-brained ideology.

Stanford University administrators in May published an index of forbidden words to be eliminated from the school’s websites and computer code, and provided inclusive replacements to help re-educate the benighted.

Call yourself an “American”? Please don’t. Better to say “U.S. citizen,” per the bias hunters, lest you slight the rest of the Americas. “Immigrant” is also out, with “person who has immigrated” as the approved alternative. It’s the iron law of academic writing: Why use one word when four will do?

You can’t “master” your subject at Stanford any longer; in case you hadn’t heard, the school instructs that “historically, masters enslaved people.” And don’t dare design a “blind study,” which “unintentionally perpetuates that disability is somehow abnormal or negative, furthering an ableist culture.” Blind studies are good and useful, but never mind; “masked study” is to be preferred. Follow the science.

“Gangbusters” is banned because the index says it “invokes the notion of police action against ‘gangs’ in a positive light, which may have racial undertones.” Not to beat a dead horse (a phrase that the index says “normalizes violence against animals”), but you used to have to get a graduate degree in the humanities to write something that stupid.

The Elimination of Harmful Language Initiative is a “multi-phase” project of Stanford’s IT leaders. The list took “18 months of collaboration with stakeholder groups” to produce, the university tells us. We can’t imagine what’s next, except that it will surely involve more make-work for more administrators, whose proliferation has driven much of the rise in college tuition and student debt. For 16,937 students, Stanford lists 2,288 faculty and 15,750 administrative staff.

The list was prefaced with (to use another forbidden word) a trigger warning: “This website contains language that is offensive or harmful. Please engage with this website at your own pace.”

RTWT

04 Aug 2021

HT: Bernie Sanders (not the communist one).

24 Jun 2021

Daily Mail:

A liberal arts college in Massachusetts has warned its students and faculty against using ‘violent language’ – even banning the phrase ‘trigger warning’ for its association with guns.

Brandeis University in Waltham has created an anti-violence resource called the Prevention, Advocacy & Resource Center which provides information and advice to students and staff.

It lists words and idioms, including ‘picnic’ and ‘rule of thumb,’ which it claims are ‘violent’ and suggests dreary alternatives such as ‘outdoor eating’ for the former and ‘general rule’ for the latter. …

In addition to its page of ‘violent language’ the college has a whole section dedicated to ‘oppressive language,’ which includes ‘identity-based language,’ ‘language that doesn’t say what we mean,’ ‘culturally appropriative language’ and ‘person-first alternatives’

“Violent language” list.

RTWT

04 Jan 2021

The Sun reports that you can be an ordained Methodist minister and be elected to Congress and not understand the meaning of the word “Amen” concluding Christian prayers.

A democratic congressman has sparked fury after ending a prayer with “amen and awomen”.

Rep. Emanuel Cleaver, an ordained United Methodist minister from Missouri, also mentioned the Hindu god Brahma while praying at the opening of Congress.

He said: “We ask it in the name of the monotheistic God, Brahma, and ‘god’ known by many names by many different faiths.”

“Amen and awomen,” he said as he closed the prayer.

RTWT

Amen comes from Old English, via ecclesiastical Latin, via Greek amēn, from Hebrew ‘āmēn ‘truth, certainty’, and is used adverbially as an expression of agreement. It adopted in the Septuagint as a solemn expression of belief or affirmation.

30 Oct 2019

Katie Heaney, at The Cut, explains:

Recently, I saw a conversation between a few women I follow on Twitter about Fiona Apple, who was profiled by Vulture last month. In the course of her interview, Apple mentions that she’s stopped drinking, but has started smoking more weed instead: “Alcohol helped me for a while, but I don’t drink anymore,†she says. “Now it’s just pot, pot, pot.†This was the part of the interview the women were discussing. “Fiona Apple: Cali sober??†one wrote.

The term “Cali sober†here refers to people who don’t drink but do smoke weed, though internet definitions vary slightly: Urban Dictionary says it means people who drink and smoke weed but don’t do other drugs; an essay by journalist Michelle Lhooq uses it to refer to her decision to smoke weed and do psychedelics, but not drink. While the term is new to me, the behavior it describes is not. …

RTWT

27 Sep 2019

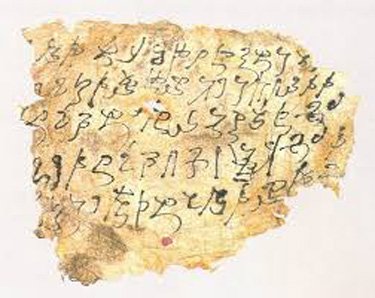

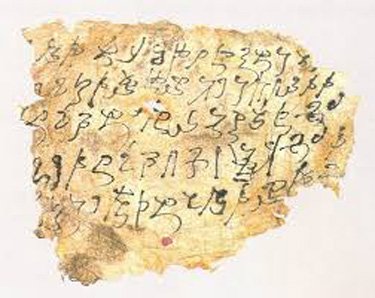

According to Language Log, the plot thickens.

[There was] excitement generated a few months ago by the announcement that “Tocharian C,” the native language of Kroraina (Chinese Loulan) had been discovered, hiding, as it were, in certain documents written in the Kharoá¹£á¹hÄ« script (“Tocharian C: its discovery and implications” [4/2/19]). Those documents, with transcription, grammatical sketch, and glossary, were published earlier this year as a part of Klaus T. Schmidt’s Nachlass (Stefan Zimmer, editor, Hampen in Bremen, publisher). However, on the weekend of September 15th and 16th a group of distinguished Tocharianists (led by Georges Pinault and Michaël Peyrot), accompanied by at least one specialist in Central Asian Iranian languages, languages normally written in Kharoá¹£á¹hÄ«, met in Leiden to examine the texts and Schmidt’s transcriptions. The result is disappointing, saddening even. In Peyrot’s words, “not one word is transcribed correctly.” We await a full report of the “Leiden Group” with a more accurate transcription and linguistic commentary (for instance, is this an already known Iranian or Indic language, or do the texts represent more than one language, one of which might be a Tocharian language?). Producing such a report is a tall order and we may not have it for some little time. But, at the very least, Schmidt’s “Tocharian C,” as it stands, has been removed from the plane of real languages and moved to some linguistic parallel universe.

So, what do we have in Schmidt’s “Tocharian C”? I can think of three scenarios, perhaps there are more. First, Schmidt may have subconsciously read into his texts what he wanted to be there. There have certainly been such things happening (the well-known first “transcription” of the Voynich Manuscript by William Romaine Newbold* is such a case). Secondly, and less generously, it may have been an outright fabrication, an attempt at deception. But, what would have been the purpose? Thirdly, and more generously, it might have been a kind of “Tocharian Sindarin”—a created language such as Tolkien played so artistically with, given a certain literary verisimilitude by the reference to old manuscripts where it might be found. If so, it was not meant to deceive, but his family, not having been told of its true nature, passed it on to Zimmer as real. And Zimmer, not being a reader of the Kharoá¹£á¹hÄ« script (precious few Tocharianists are), naturally enough took Schmidt’s transcriptions at face value.

02 Sep 2019

From midget faded rattlesnake, at Ricochet:

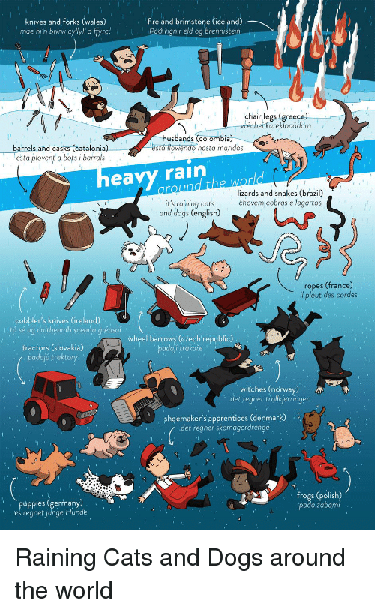

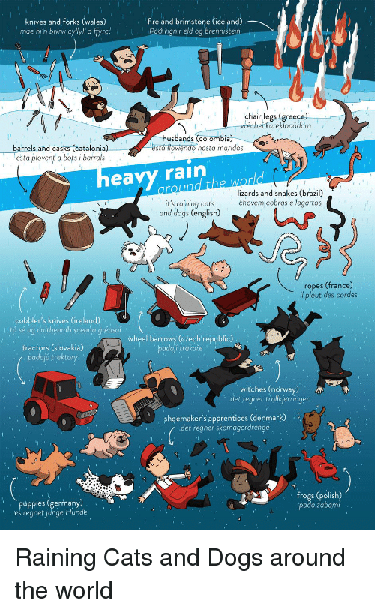

In English, we say, “It’s raining cats and dogs.†Explanations for why we say this are numerous, and all fairly dubious. In other lands, other stuff falls from the sky during heavy storms. In Croatia, axes; in Bosnia, crowbars (I’m sensing a pattern here); in France and Sweden, nails. In several countries, heavy rain falls like pestle onto mortar. In English, it may also rain like pitchforks or darning needles. While idioms describing heavy rain as the piss from some great creature (a cow or a god) may not be surprising, a few idioms kick it up a notch (so to speak), describing the rain as falling dung.

And then there are the old ladies falling out of skies. Sometimes with sticks, sometimes without. Sometimes old ladies beaten with ugly sticks. The Flemish say, het regent oude wijven — it’s raining old women. The Afrikaners, more savagely, arm the old women with clubs: ou vrouens met knopkieries reën. Yes, good ol’ knobkerries — ugly sticks, indeed! Afrikaners and the Flemish speak variants of Dutch, so it’s not surprising they share cataracts of crones, armed or not. Why the Welsh also share them is more of a mystery, but yn’ Gymraeg, again we find old ladies raining with sticks: mae hi’n bwrw hen wragedd a ffyn. Traveling to Norway, we find the outpouring of old ladies beaten with the ugly sticks: det regner trollkjerringer — it’s raining she-trolls.

I think the above illustration would have been better with literal female trolls.

16 Jun 2019

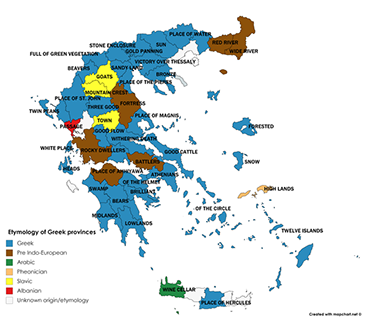

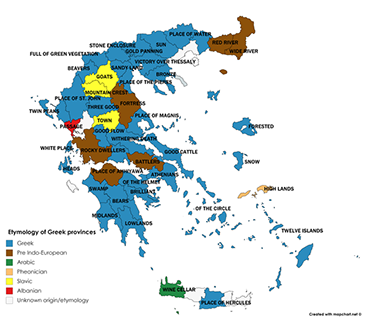

(click on image for larger version)

/div>

Feeds

|