Category Archive 'Easter Island'

29 Mar 2021

Atlas Obscura discusses the effort to decipher the Rongorongo script.

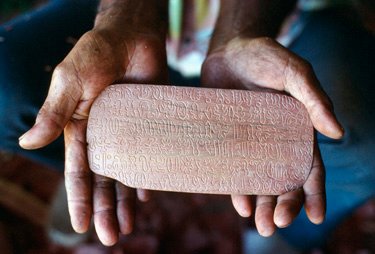

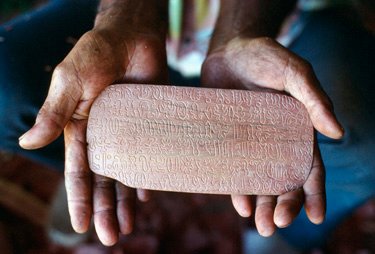

On the outskirts of Hanga Roa, Easter Island’s only town, the Museo Rapa Nui has a small but striking collection. It includes a rare female version of the monolithic statues known as moai, and sets of piercing moai eyes made from white coral and red volcanic rock. Finely worked obsidian tools sit alongside displays on the Birdman contest, which involved swimming through shark-infested waters and searching an offshore islet for a seabird egg in order to claim the spiritual leadership of Easter Island. With so much to see, it’s easy to overlook the carved wooden fish in a glass cabinet. Raised on a stand, as if held aloft by a proud angler, it is the color of dark chocolate and roughly the size and shape of an oar blade. The design may be relatively simple, but this object represents a great—and unsolved—linguistic puzzle.

The fish is covered with rows of stylized glyphs. Some resemble human forms and animals and plants, while others are more abstract—circles, crosses, chevrons, lozenges. This is rongorongo, the only indigenous writing system to develop in Oceania before the 20th century and, according to James Grant-Peterkin, author of A Companion to Easter Island, one of “the last remaining mysteries on Easter Island.”

Known locally by its Polynesian name Rapa Nui, Easter Island is the remotest inhabited island on Earth, 1,298 miles from its nearest populated neighbor. According to oral traditions, rongorongo tablets were brought here by the first settlers, who arrived between the years 800 and 1200, probably from the Marquesas or Gambier islands, which are now part of French Polynesia. Academics disagree about when the writing system emerged. Some believe it long predated European contact—which began when Dutch navigator Jacob Roggeveen reached the island on Easter Sunday 1722—while others argue that it emerged as late as the 1770s, after the Rapanui people saw European writing for the first time during a Spanish expedition to the island.

It appears that rongorongo was primarily used for religious purposes and only understood by the local elites. “Rongorongo was never a script of the common people,” says Cristián Moreno Pakarati, head of research at the Rapanui Pioneers Society. “Only a handful of wise literate people, according to tradition only men, could interpret the texts.” Knowledge of the script began to disappear in the 19th century, he adds. “The Rapanui population faced the disintegrating forces of the West in the form of disease epidemics, piracy, ‘blackbirding’ slave raids [in which up to 1,500 islanders were kidnapped and forced to work in Peru] and religious indoctrination.” As the Rapanui population declined by approximately 95 percent—a census in 1877 recorded just 111 Rapanui islanders—only a fragmentary understanding of rongorongo survived.

But the knowledge was never completely lost, says Steven Roger Fischer, former director of the Institute of Polynesian Languages and Literatures in Auckland, New Zealand, and author of Island at the End of the World, A History of Writing, and A History of Reading. “Several Rapanui still remembered the traditions, some chants and customs, and relayed a few of these things to foreign visitors well into the first two decades of the 20th century.”

Some of these visitors took notes on what they heard about rongorongo, and over the years, there have been various attempts to decipher the script, but it has proved a difficult task. One problem is the lack of data. Only 26 rongorongo objects have survived—the Museo Rapa Nui’s is a replica, and the originals are all overseas, predominantly in Europe, the United States, and mainland Chile. Some have only a few lines of text. “Some rock carvings on the island [have individual symbols that] are very similar to rongorongo, but there isn’t a line of text anywhere,” says Grant-Peterkin.

RTWT

17 Feb 2018

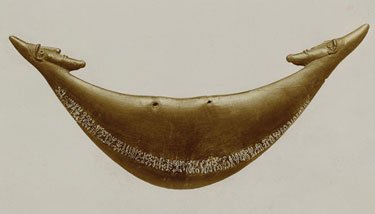

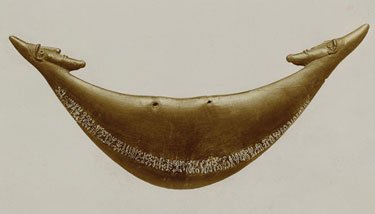

A crescent-shaped, wooden neck ornament from Easter Island made some time in the first half of the nineteenth century. The artifact, decorated with two bearded male heads on either end, contains a line of rongorongo glyphs along its bottom edge. British Museum.

Jacob Mikanowski, in Cabinet Magazine, introduces us to the Linear B of the Pacific: rongrongo.

Of all the literatures in the world, the smallest and most enigmatic belongs without question to the people of Easter Island. It is written in a script—rongorongo—that no one can decipher. Experts cannot even agree whether it is an alphabet, a syllabary, a mnemonic, or a rebus. Its entire corpus consists of two dozen texts. The longest, consisting of a few thousand signs, winds its way around a magnificent ceremonial staff. The shortest texts—if they can even be called that—consist of barely more than a single sign. One took the form of a tattoo on a man’s back. Another was carved onto a human skull.

Where did the rongorongo script come from? What do its texts communicate? No one knows for sure. The last Easter Islanders (or Rapanui) familiar with rongorongo died in the nineteenth century. They didn’t live long enough to pass on the secret of their writing system, but they did leave a few tantalizing clues. The island’s spoken language, also called Rapanui, lives on, but today it is written in a Latin script and its relationship to rongorongo is unclear. So far at least, no one has successfully connected one with the other. To this day, rongorongo remains a puzzle, an enigma, and a mirror for the folly of those who try to solve it.

Rongorongo is the only script native to the Pacific. Like so much else, it makes Easter Island unique.

15 Jul 2017

Take Easter Island. For a long time now, we’ve been told the resident culture’s decline constitutes a cautionary tale about environmental destruction via human excess.

A new study paints a completely different picture. New Atlas:

When Europeans first landed on Easter Island in the 18th century, they found a barren landscape. The story goes that to raise the huge stone heads, called moai, the Rapa Nui people felled most of the island’s trees to use as rollers, burning the rest for fuel and warmth. The negative effects of a treeless island cascaded down, destroying their previous prosperity and leaving the tribes fighting over resources.

“The traditional story is that over time the people of Rapa Nui used up their resources and started to run out of food,” says Carl Lipo, co-author of the study. “One of the resources that they supposedly used up was trees that were growing on the island. Those trees provided canoes and, as a result of the lack of canoes, they could no longer fish. So they started to rely more and more on land food. As they relied on land food, productivity went down because of soil erosion, which led to crop failures … painting the picture of this sort of catastrophe. That’s the traditional narrative.”

To get a better understanding of what the people of Easter Island were eating and how, a team from Binghamton University analyzed human, animal and plant remains dating as far back as 1400 CE. Analyzing the carbon and nitrogen isotopes of the collagen in bones can reveal the diet of ancient people, and these were compared with isotope analyses of the ancient and modern plant and marine samples to get an idea of where their food was coming from.

The results showed that about half of the proteins the Rapa Nui people were consuming came from marine sources, which means they were fishing more consistently for a longer period than they were given credit for. At the same time, the food they were cultivating on land was more productive than previously thought, with the environmental analyses showing an understanding of how to improve poor soil fertility.

“We found that there’s a fairly significant marine diet, over time, throughout history and that people were eating marine resources, and it wasn’t as though they only had food from terrestrial resources,” says Lipo. “We also learned that what they did get from terrestrial resources came from very modified soils, that they were enriching the soils in order to grow the crops. That supports the argument we’ve made in our previous work, that these people came up with an ingenious strategy in enriching the soils by adding bedrock to the surface and inside the soil to create, essentially, fertilizer to support their populations, and that forest loss really isn’t a catastrophe as previously described.”

Although the story of the Rapa Nui’s self-destruction serves as a good fable to teach environmental awareness and responsibility, the Binghamton team concludes that it’s not that simple. The history of Easter Island is more nuanced, and the ancient people shouldn’t be written off as reckless and careless.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Easter Island' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|