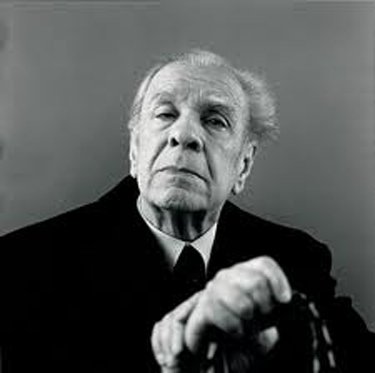

Borges Hated Soccer

Fascism, Games Versus Sport, Jorge Luis Borges, Mass Culture, Nationalism, Soccer

Shaj Matthew, in the New Republic, explains why one of the last century’s greatest writers justly despised his own country’s national obsession.

Soccer is popular,†Jorge Luis Borges observed, “because stupidity is popular.â€

At first glance, the Argentine writer’s animus toward “the beautiful game” seems to reflect the attitude of today’s typical soccer hater, whose lazy gibes have almost become a refrain by now: Soccer is boring. There are too many tie scores. I can’t stand the fake injuries.

And it’s true: Borges did call soccer “aesthetically ugly.†He did say, “Soccer is one of England’s biggest crimes.†And apparently, he even scheduled one of his lectures so that it would intentionally conflict with Argentina’s first game of the 1978 World Cup. But Borges’ distaste for the sport stemmed from something far more troubling than aesthetics. His problem was with soccer fan culture, which he linked to the kind of blind popular support that propped up the leaders of the twentieth century’s most horrifying political movements. In his lifetime, he saw elements of fascism, Peronism, and even anti-Semitism emerge in the Argentinean political sphere, so his intense suspicion of popular political movements and mass culture—the apogee of which, in Argentina, is soccer—makes a lot of sense. (“There is an idea of supremacy, of power, [in soccer] that seems horrible to me,†he once wrote.) Borges opposed dogmatism in any shape or form, so he was naturally suspicious of his countrymen’s unqualified devotion to any doctrine or religion—even to their dear albiceleste.

Soccer is inextricably tied to nationalism, another one of Borges’ objections to the sport. “Nationalism only allows for affirmations, and every doctrine that discards doubt, negation, is a form of fanaticism and stupidity,†he said. National teams generate nationalistic fervor, creating the possibility for an unscrupulous government to use a star player as a mouthpiece to legitimize itself. In fact, that’s precisely what happened with one of the greatest players ever: Pelé. “Even as his government rounded up political dissidents, it also produced a giant poster of Pelé straining to head the ball through the goal, accompanied by the slogan Ninguém mais segura este paÃs: Nobody can stop this country now,†writes Dave Zirin in his new book, Brazil’s Dance with the Devil. Governments, such as the Brazilian military dictatorship that Pelé played under, can take advantage of the bond that fans share with their national teams to drum up popular support, and this is what Borges feared—and resented—about the sport.

Read the whole thing.

Hat tip to the Dish.

Borges, of course, was perfectly right.

Soccer is just the most popular commercial team game in the world outside the United States. All commercial team games are modern developments organized originally by carnival impresarios to separate the urban proletarian from his beer nickel. These teams and the games they play are totally and completely meaningless spectacles performed purely for commercial purposes. The teams’ regional identifications and mascots are utterly meaningless. Players come from anywhere. Teams may be sold and relocated, coaches and recognizable styles of play & performance may be routinely altered on the basis of owners’ whims at the any moment.

Commercial game teams stand for absolutely nothing, and fan identification and loyalty is, as Borges recognized, a kind of willful stupidity constituting an intentional surrender of self to a totally ersatz sort of group identity.