Category Archive 'Hagiography'

11 Nov 2022

–An annual post–

WWI came to an end by an armistice arranged to occur at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918. The date and time, selected at a point in history when mens’ memories ran much longer, represented a compliment to St. Martin, patron saint of soldiers, and thus a tribute to the fighting men of both sides. The feast day of St. Martin, the Martinmas, had been for centuries a major landmark in the European calendar, a date on which leases expired, rents came due; and represented, in Northern Europe, a seasonal turning point after which cold weather and snow might be normally expected.

It fell about the Martinmas-time, when the snow lay on the borders…

—Old Song.

From Robert Chambers, The Book of Days, 1869:

St. Martin, the son of a Roman military tribune, was born at Sabaria, in Hungary, about 316. From his earliest infancy, he was remarkable for mildness of disposition; yet he was obliged to become a soldier, a profession most uncongenial to his natural character. After several years’ service, he retired into solitude, from whence he was withdrawn, by being elected bishop of Tours, in the year 374.

The zeal and piety he displayed in this office were most exemplary. He converted the whole of his diocese to Christianity, overthrowing the ancient pagan temples, and erecting churches in their stead. From the great success of his pious endeavours, Martin has been styled the Apostle of the Gauls; and, being the first confessor to whom the Latin Church offered public prayers, he is distinguished as the father of that church. In remembrance of his original profession, he is also frequently denominated the Soldier Saint.

The principal legend, connected with St. Martin, forms the subject of our illustration, which represents the saint, when a soldier, dividing his cloak with a poor naked beggar, whom he found perishing with cold at the gate of Amiens. This cloak, being most miraculously preserved, long formed one of the holiest and most valued relics of France; when war was declared, it was carried before the French monarchs, as a sacred banner, and never failed to assure a certain victory. The oratory in which this cloak or cape—in French, chape—was preserved, acquired, in consequence, the name of chapelle, the person intrusted with its care being termed chapelain: and thus, according to Collin de Plancy, our English words chapel and chaplain are derived. The canons of St. Martin of Tours and St. Gratian had a lawsuit, for sixty years, about a sleeve of this cloak, each claiming it as their property. The Count Larochefoucalt, at last, put an end to the proceedings, by sacrilegiously committing the contested relic to the flames.

Another legend of St. Martin is connected with one of those literary curiosities termed a palindrome. Martin, having occasion to visit Rome, set out to perform the journey thither on foot. Satan, meeting him on the way, taunted the holy man for not using a conveyance more suitable to a bishop. In an instant the saint changed the Old Serpent into a mule, and jumping on its back, trotted comfortably along. Whenever the transformed demon slackened pace, Martin, by making the sign of the cross, urged it to full speed. At last, Satan utterly defeated, exclaimed:

Signa, te Signa: temere me tangis et angis:

Roma tibi subito motibus ibit amor.’

In English—

‘Cross, cross thyself: thou plaguest and vexest me without necessity;

for, owing to my exertions, thou wilt soon reach Rome, the object of thy wishes.’

The singularity of this distich, consists in its being palindromical—that is, the same, whether read backwards or forwards. Angis, the last word of the first line, when read backwards, forming signet, and the other words admitting of being reversed, in a similar manner.

The festival of St. Martin, happening at that season when the new wines of the year are drawn from the lees and tasted, when cattle are killed for winter food, and fat geese are in their prime, is held as a feast-day over most parts of Christendom. On the ancient clog almanacs, the day is marked by the figure of a goose; our bird of Michaelmas being, on the continent, sacrificed at Martinmas. In Scotland and the north of England, a fat ox is called a mart, clearly from Martinmas, the usual time when beeves are killed for winter use. In ‘Tusser’s Husbandry, we read:

When Easter comes, who knows not then,

That veal and bacon is the man?

And Martilmass beef doth bear good tack,

When country folic do dainties lack.’

Barnaby Googe’s translation of Neogeorgus, shews us how Martinmas was kept in Germany, towards the latter part of the fifteenth century

‘To belly chear, yet once again,

Doth Martin more incline,

Whom all the people worshippeth

With roasted geese and wine.

Both all the day long, and the night,

Now each man open makes

His vessels all, and of the must,

Oft times, the last he takes,

Which holy Martin afterwards

Alloweth to be wine,

Therefore they him, unto the skies,

Extol with praise divine.’

A genial saint, like Martin, might naturally be expected to become popular in England; and there are no less than seven churches in London and Westminster, alone, dedicated to him. There is certainly more than a resemblance between the Vinalia of the Romans, and the Martinalia of the medieval period. Indeed, an old ecclesiastical calendar, quoted by Brand, expressly states under 11th November: ‘The Vinalia, a feast of the ancients, removed to this day. Bacchus in the figure of Martin.’ And thus, probably, it happened, that the beggars were taken from St. Martin, and placed under the protection of St. Giles; while the former became the patron saint of publicans, tavern-keepers, and other ‘dispensers of good eating and drinking. In the hall of the Vintners’ Company of London, paintings and statues of St. Martin and Bacchus reign amicably together side by side.

On the inauguration, as lord mayor, of Sir Samuel Dashwood, an honoured vintner, in 1702, the company had a grand processional pageant, the most conspicuous figure in which was their patron saint, Martin, arrayed, cap-Ã -pie, in a magnificent suit of polished armour; wearing a costly scarlet cloak, and mounted on a richly plumed and caparisoned white charger: two esquires, in rich liveries, walking at each side. Twenty satyrs danced before him, beating tambours, and preceded by ten halberdiers, with rural music. Ten Roman lictors, wearing silver helmets, and carrying axes and fasces, gave an air of classical dignity to the procession, and, with the satyrs, sustained the bacchanalian idea of the affair.

A multitude of beggars, ‘howling most lamentably,’ followed the warlike saint, till the procession stopped in St. Paul’s Churchyard. Then Martin, or his representative at least, drawing his sword, cut his rich scarlet cloak in many pieces, which he distributed among the beggars. This ceremony being duly and gravely performed, the lamentable howlings ceased, and the procession resumed its course to Guildhall, where Queen Anne graciously condescended to dine with the new lord mayor.

23 Apr 2022

Hans von Aachen, St. George Slaying the Dragon, c. 1600, Private Collection, London

From Robert Chambers, The Book of Days, 1869:

Butler, the historian of the Romish calendar, repudiates George of Cappadocia, and will have it that the famous saint was born of noble Christian parents, that he entered the army, and rose to a high grade in its ranks, until the persecution of his co-religionists by Diocletian compelled him to throw up his commission, and upbraid the emperor for his cruelty, by which bold conduct he lost his head and won his saintship. Whatever the real character of St. George might have been, he was held in great honour in England from a very early period. While in the calendars of the Greek and Latin churches he shared the twenty-third of April with other saints, a Saxon Martyrology declares the day dedicated to him alone; and after the Conquest his festival was celebrated after the approved fashion of Englishmen.

In 1344, this feast was made memorable by the creation of the noble Order of St. George, or the Blue Garter, the institution being inaugurated by a grand joust, in which forty of England’s best and bravest knights held the lists against the foreign chivalry attracted by the proclamation of the challenge through France, Burgundy, Hainault, Brabant, Flanders, and Germany. In the first year of the reign of Henry V, a council held at London decreed, at the instance of the king himself, that henceforth the feast of St. George should be observed by a double service; and for many years the festival was kept with great splendour at Windsor and other towns. Shakspeare, in Henry VI, makes the Regent Bedford say, on receiving the news of disasters in France:

Bonfires in France I am forthwith to make

To keep our great St. George’s feast withal!’

Edward VI promulgated certain statutes severing the connection between the ‘noble order’ and the saint; but on his death, Mary at once abrogated them as ‘impertinent, and tending to novelty.’ The festival continued to be observed until 1567, when, the ceremonies being thought incompatible with the reformed religion, Elizabeth ordered its discontinuance. James I, however, kept the 23rd of April to some extent, and the revival of the feast in all its glories was only prevented by the Civil War. So late as 1614, it was the custom for fashionable gentlemen to wear blue coats on St. George’s day, probably in imitation of the blue mantle worn by the Knights of the Garter.

In olden times, the standard of St. George was borne before our English kings in battle, and his name was the rallying cry of English warriors. According to Shakspeare, Henry V led the attack on Harfleur to the battle-cry of ‘God for Harry! England! and St. George!’ and ‘God and St. George’ was Talbot’s slogan on the fatal field of Patay. Edward of Wales exhorts his peace-loving parents to

‘Cheer these noble lords,

And hearten those that fight in your defence;

Unsheath your sword, good father, cry St. George!’

The fiery Richard invokes the same saint, and his rival can think of no better name to excite the ardour of his adherents:

‘Advance our standards, set upon our foes,

Our ancient word of courage, fair St. George,

Inspire us with the spleen of fiery dragons.’

England was not the only nation that fought under the banner of St. George, nor was the Order of the Garter the only chivalric institution in his honour. Sicily, Arragon, Valencia, Genoa, Malta, Barcelona, looked up to him as their guardian saint; and as to knightly orders bearing his name, a Venetian Order of St. George was created in 1200, a Spanish in 1317, an Austrian in 1470, a Genoese in 1472, and a Roman in 1492, to say nothing of the more modern ones of Bavaria (1729), Russia (1767), and Hanover (1839).

Legendarily the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George was founded by the Emperor Constantine (312-337 A.D.). On the factual level, the Constantinian Order is known to have functioned militarily in the Balkans in the 15th century against the Turk under the authority of descendants of the twelfth-century Byzantine Emperor Isaac II Angelus Comnenus.

We Lithuanians liked St. George as well. When I was a boy I attended St. George Lithuanian Parish Elementary School, and served mass at St. George Lithuanian Roman Catholic Church in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania.

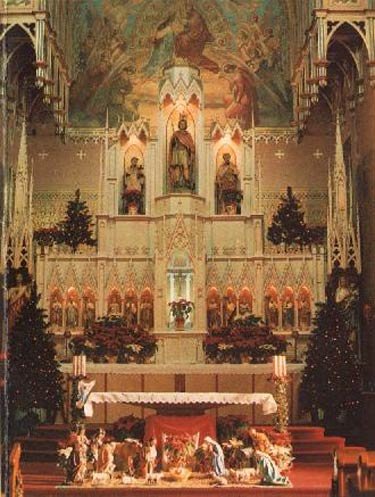

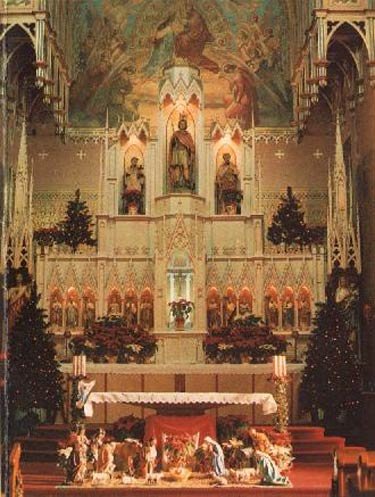

St. George Church, Shenandoah, Pennsylvania, Christmas, 1979. This church, built by immigrant coal miners in 1891, was torn down by the Diocese of Allentown in 2010.

17 Mar 2022

From Robert Chambers, The Book of Days, 1869:

LEGENDARY HISTORY OF ST. PATRICK

Almost as many countries arrogate the honour of having been the natal soil of St. Patrick, as made a similar claim with respect to Homer. Scotland, England, France, and Wales, each furnish their respective pretensions: but, whatever doubts may obscure his birthplace, all agree in stating that, as his name implies, he was of a patrician family. He was born about the year 372, and when only sixteen years of age, was carried off by pirates, who sold him into slavery in Ireland; where his master employed him as a swineherd on the well-known mountain of Sleamish, in the county of Antrim. Here he passed seven years, during which time he acquired a knowledge of the Irish language, and made himself acquainted with the manners, habits, and customs of the people. Escaping from captivity, and, after many adventures, reaching the Continent, he was successively ordained deacon, priest, and bishop: and then once more, with the authority of Pope Celestine, he returned to Ireland to preach the Gospel to its then heathen inhabitants.

The principal enemies that St. Patrick found to the introduction of Christianity into Ireland, were the Druidical priests of the more ancient faith, who, as might naturally be supposed, were exceedingly adverse to any innovation. These Druids, being great magicians, would have been formidable antagonists to any one of less miraculous and saintly powers than Patrick. Their obstinate antagonism was so great, that, in spite of his benevolent disposition, he was compelled to curse their fertile lands, so that they became dreary bogs: to curse their rivers, so that they produced no fish: to curse their very kettles, so that with no amount of fire and patience could they ever be made to boil; and, as a last resort, to curse the Druids themselves, so that the earth opened and swallowed them up. …

The greatest of St. Patrick’s miracles was that of driving the venomous reptiles out of Ireland, and rendering the Irish soil, for ever after, so obnoxious to the serpent race, that they instantaneously die on touching it. Colgan seriously relates that St. Patrick accomplished this feat by beating a drum, which he struck with such fervour that he knocked a hole in it, thereby endangering the success of the miracle. But an angel appearing mended the drum: and the patched instrument was long exhibited as a holy relic. …

When baptizing an Irish chieftain, the venerable saint leaned heavily on his crozier, the steel-spiked point of which he had unwittingly placed on the great toe of the converted heathen. The pious chief, in his ignorance of Christian rites, believing this to be an essential part of the ceremony, bore the pain without flinching or murmur; though the blood flowed so freely from the wound, that the Irish named the place St. fhuil (stream of blood), now pronounced Struill, the name of a well-known place near Downpatrick. And here we are reminded of a very remarkable fact in connection with geographical appellations, that the footsteps of St. Patrick can be traced, almost from his cradle to his grave, by the names of places called after him.

Thus, assuming his Scottish origin, he was born at Kilpatrick (the cell or church of Patrick), in Dumbartonshire. He resided for some time at Dalpatrick (the district or division of Patrick), in Lanarkshire; and visited Crag-phadrig (the rock of Patrick), near Inverness. He founded two churches, Kirkpatrick at Irongray, in Kireudbright; and Kirkpatrick at Fleming, in Dumfries: and ultimately sailed from Portpatrick, leaving behind him such an odour of sanctity, that among the most distinguished families of the Scottish aristocracy, Patrick has been a favourite name down to the present day.

Arriving in England, he preached in Patterdale (Patrick’s dale), in Westmoreland: and founded the church of Kirkpatrick, in Durham. Visiting Wales, he walked over Sarn-badrig (Patrick’s causeway), which, now covered by the sea, forms a dangerous shoal in Carnarvon Bay: and departing for the Continent, sailed from Llan-badrig (the church of Patrick), in the island of Anglesea. Undertaking his mission to convert the Irish, he first landed at Innis-patrick (the island of Patrick), and next at Holmpatrick, on the opposite shore of the mainland, in the county of Dublin. Sailing northwards, he touched at the Isle of Man, sometimes since, also, called. Innis-patrick, where he founded another church of Kirkpatrick, near the town of Peel. Again landing on the coast of Ireland, in the county of Down, he converted and baptized the chieftain Dichu, on his own threshing-floor. The name of the parish of Saul, derived from Sabbal-patrick (the barn of Patrick), perpetuates the event. He then proceeded to Temple-patrick, in Antrim, and from thence to a lofty mountain in Mayo, ever since called Croagh-patrick.

He founded an abbey in East Meath, called Domnach-Padraig (the house of Patrick), and built a church in Dublin on the spot where St. Patrick’s Cathedral now stands. In an island of Lough Deng, in the county of Donegal, there is St. Patrick’s Purgatory: in Leinster, St. Patrick’s Wood; at Cashel, St. Patrick’s Rock; the St. Patrick’s Wells, at which the holy man is said to have quenched his thirst, may be counted by dozens. He is commonly stated to have died at Saul on the 17th of March 493, in the one hundred and twenty-first year of his age. …

The shamrock, or small white clover (trifolium repens of botanists), is almost universally worn in the hat over all Ireland, on St. Patrick’s day. The popular notion is, that when St. Patrick was preaching the doctrine of the Trinity to the pagan Irish, he used this plant, bearing three leaves upon one stem, as a symbol or illustration of the great mystery. To suppose, as some absurdly hold, that he used it as an argument, would be derogatory to the saint’s high reputation for orthodoxy and good sense: but it is certainly a curious coincidence, if nothing more, that the trefoil in Arabic is called skamrakh, and was held sacred in Iran as emblematical of the Persian Triads. Pliny, too, in his Natural History, says that serpents are never seen upon trefoil, and it prevails against the stings of snakes and scorpions. This, considering St. Patrick’s connexion with snakes, is really remarkable, and we may reasonably imagine that, previous to his arrival, the Irish had ascribed mystical virtues to the trefoil or shamrock, and on hearing of the Trinity for the first time, they fancied some peculiar fitness in their already sacred plant to shadow forth the newly revealed and mysterious doctrine. …

In the Galtee or Gaultie Mountains, situated between the counties of Cork and Tipperary, there are seven lakes, in one of which, called Lough Dilveen, it is said Saint Patrick, when banishing the snakes and toads from Ireland, chained a monster serpent, telling him to remain there till Monday.

The serpent every Monday morning calls out in Irish, ‘It is a long Monday, Patrick.’

That St Patrick chained the serpent in Lough Dilveen, and that the serpent calls out to him every Monday morning, is firmly believed by the lower orders who live in the neighbourhood of the Lough.

14 Feb 2022

Jacopo Bassano, St Valentine Baptizing St Lucilla, 1575, oil on canvas, Museo Civico, Bassano del Grappa

The popular customs associated with Saint Valentine’s Day undoubtedly had their origin in a conventional belief generally received in England and France during the Middle Ages, that on 14 February, i.e., half way through the second month of the year, the birds began to pair. Thus in Chaucer’s Parliament of Foules we read:

For this was sent on Seynt Valentyne’s day

Whan every foul cometh ther to choose his mate.

For this reason the day was looked upon as specially consecrated to lovers and as a proper occasion for writing love letters and sending lovers’ tokens. Both the French and English literatures of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries contain allusions to the practice. Perhaps the earliest to be found is in the 34th and 35th Ballades of the bilingual poet, John Gower, written in French; but Lydgate and Clauvowe supply other examples. Those who chose each other under these circumstances seem to have been called by each other their Valentines.

In the Paston Letters, Dame Elizabeth Brews writes thus about a match she hopes to make for her daughter (we modernize the spelling), addressing the favoured suitor:

And, cousin mine, upon Monday is Saint Valentine’s Day and every bird chooses himself a mate, and if it like you to come on Thursday night, and make provision that you may abide till then, I trust to God that ye shall speak to my husband and I shall pray that we may bring the matter to a conclusion.

——————————————–

From Robert Chambers, The Book of Days, 1869: Feast Day: St. Valentine, priest and martyr, circ. 270.

Valentine’s Day is now almost everywhere a much degenerated festival, the only observance of any note consisting merely of the sending of jocular anonymous letters to parties whom one wishes to quiz, and this confined very much to the humbler classes. The approach of the day is now heralded by the appearance in the print-sellers’ shop windows of vast numbers of missives calculated for use on this occasion, each generally consisting of a single sheet of post paper, on the first page of which is seen some ridiculous coloured caricature of the male or female figure, with a few burlesque verses below. More rarely, the print is of a sentimental kind, such as a view of Hymen’s altar, with a pair undergoing initiation into wedded happiness before it, while Cupid flutters above, and hearts transfixed with his darts decorate the corners. Maid-servants and young fellows interchange such epistles with each other on the 14th of February, no doubt conceiving that the joke is amazingly good: and, generally, the newspapers do not fail to record that the London postmen delivered so many hundred thousand more letters on that day than they do in general. Such is nearly the whole extent of the observances now peculiar to St. Valentine’s Day.

At no remote period it was very different. Ridiculous letters were unknown: and, if letters of any kind were sent, they contained only a courteous profession of attachment from some young man to some young maiden, honeyed with a few compliments to her various perfections, and expressive of a hope that his love might meet with return. But the true proper ceremony of St. Valentine’s Day was the drawing of a kind of lottery, followed by ceremonies not much unlike what is generally called the game of forfeits. Misson, a learned traveller, of the early part of the last century, gives apparently a correct account of the principal ceremonial of the day.

‘On the eve of St. Valentine’s Day,’ he says, ‘the young folks in England and Scotland, by a very ancient custom, celebrate a little festival. An equal number of maids and bachelors get together: each writes their true or some feigned name upon separate billets, which they roll up, and draw by way of lots, the maids taking the men’s billets, and the men the maids’: so that each of the young men lights upon a girl that he calls his valentine, and each of the girls upon a young man whom she calls hers. By this means each has two valentines: but the man sticks faster to the valentine that has fallen to him than to the valentine to whom he is fallen. Fortune having thus divided the company into so many couples, the valentines give balls and treats to their mistresses, wear their billets several days upon their bosoms or sleeves, and this little sport often ends in love.’

…

St. Valentine’s Day is alluded to by Shakspeare and by Chaucer, and also by the poet Lydgate (who died in 1440). …

The origin of these peculiar observances of St. Valentine’s Day is a subject of some obscurity. The saint himself, who was a priest of Rome, martyred in the third century, seems to have had nothing to do with the matter, beyond the accident of his day being used for the purpose. Mr. Douce, in his Illustrations of Shakspeare, says:

‘It was the practice in ancient Rome, during a great part of the month of February, to celebrate the Lupercalia, which were feasts in honour of Pan and Juno. whence the latter deity was named Februata, Februalis, and Februlla. On this occasion, amidst a variety of ceremonies, the names of young women were put into a box, from which they were drawn by the men as chance directed. The pastors of the early Christian church, who, by every possible means, endeavoured to eradicate the vestiges of pagan superstitions, and chiefly by some commutations of their forms, substituted, in the present instance, the names of particular saints instead of those of the women: and as the festival of the Lupercalia had commenced about the middle of February, they appear to have chosen St. Valentine’s Day for celebrating the new feast, because it occurred nearly at the same time.

This is, in part, the opinion of a learned and rational compiler of the Lives of the Saints, the Rev. Alban Butler.

It should seem, however, that it was utterly impossible to extirpate altogether any ceremony to which the common people had been much accustomed—a fact which it were easy to prove in tracing the origin of various other popular superstitions. And, accordingly, the outline of the ancient ceremonies was preserved, but modified by some adaptation to the Christian system. It is reasonable to suppose, that the above practice of choosing mates would gradually become reciprocal in the sexes, and that all persons so chosen would be called Valentines, from the day on which the ceremony took place.’

***********************************************

February 14th, prior to 1969, was the feast day of two, or possibly three, saints and martyrs named Valentine, all reputedly of the Third Century.

The first Valentine, legend holds, was a physician and priest in Rome, arrested for giving aid to martyrs in prison, who while there converted his jailer by restoring sight to the jailer’s daughter. He was executed by being beaten with clubs, and afterwards beheaded, February 14, 270. He is traditionally the patron of affianced couples, bee keepers, lovers, travellers, young people, and greeting card manufacturers, and his special assistance may be sought in conection with epilepsy, fainting, and plague.

A second St. Valentine, reportedly bishop of Interamna (modern Terni) was also allegedly martyred under Claudius II, and also allegedly buried along the Flaminian Way.

A third St. Valentine is said to have also been martyred in Roman times, along with companions, in Africa.

Due to an insufficiency of historical evidence in the eyes of Vatican II modernizers, the Roman Catholic Church dropped the February 14th feast of St. Valentine from its calendar in 1969.

26 Dec 2021

Rembrandt. The Martyrdom of St. Stephen. 1625. Oil on panel. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyons

From Robert Chambers, The Book of Days, 1869:

Feast Day: St. Stephen, the first martyr.

St. Stephen’s Day

To St. Stephen, the Proto-martyr, as he is generally styled, the honour has been accorded by the church of being placed in her calendar immediately after Christmas-day, in recognition of his having been the first to seal with his blood the testimony of fidelity to his Lord and Master. The year in which he was stoned to death, as recorded in the Acts of the Apostles, is supposed to have been 33 A.D. The festival commemorative of him has been retained in the Anglican calendar.

A curious superstition was formerly prevalent regarding St. Stephen’s Day — that horses should then, after being first well galloped, be copiously let blood, to insure them against disease in the course of the following year. In Barnaby Googe’s translation of Naogeorgus, the following lines occur relative to this popular notion:

Then followeth Saint Stephen’s Day, whereon doth every man

His horses jaunt and course abrode, as swiftly as he can,

Until they doe extremely sweate, and then they let them blood,

For this being done upon this day, they say doth do them good,

And keepes them from all maladies and sicknesse through the yeare,

As if that Steven any time tooke charge of horses heare.’

The origin of this practice is difficult to be accounted for, but it appears to be very ancient, and Douce supposes that it was introduced into this country by the Danes. In one of the manuscripts of that interesting chronicler, John Aubrey, who lived in the latter half of the seventeenth century, occurs the following record: On St. Stephen’s Day, the farrier came constantly and blouded all our cart-horses.’ Very possibly convenience and expediency combined on the occasion with superstition, for in Tusser Redivivus, a work published in the middle of the last century, we find this statement: ‘About Christmas is a very proper time to bleed horses in, for then they are commonly at house, then spring comes on, the sun being now coming back from the winter-solstice, and there are three or four days of rest, and if it be upon St. Stephen’s Day it is not the worse, seeing there are with it three days of rest, or at least two.’

In the parish of Drayton Beauchamp, Bucks, there existed long an ancient custom, called Stephening, from the day on which it took place. On St. Stephen’s Day, all the inhabitants used to pay a visit to the rectory, and practically assert their right to partake of as much bread and cheese and ale as they chose at the rector’s expense. On one of these occasions, according to local tradition, the then rector, being a penurious old bachelor, determined to put a stop, if possible, to this rather expensive and unceremonious visit from his parishioners. Accordingly, when St. Stephen’s Day arrived, he ordered his housekeeper not to open the window-shutters, or unlock the doors of the house, and to remain perfectly silent and motionless whenever any person was heard approaching. At the usual time the parishioners began to cluster about the house. They knocked first at one door, then at the other, then tried to open them, and on finding them fastened, they called aloud for admittance. No voice replied. No movement was heard within. ‘Surely the rector and his house-keeper must both be dead!’ exclaimed several voices at once, and a general awe pervaded the whole group. Eyes were then applied to the key-holes, and to every crevice in the window-shutters, when the rector was seen beckoning his old terrified housekeeper to sit still and silent. A simultaneous shout convinced him that his design was understood. Still he consoled himself with the hope that his larder and his cellar were secure, as the house could not be entered. But his hope was speedily dissipated. Ladders were reared against the roof, tiles were hastily thrown off, half-a-dozen sturdy young men entered, rushed down the stairs, and threw open both the outer-doors. In a trice, a hundred or more unwelcome visitors rushed into the house, and began unceremoniously to help themselves to such fare as the larder and cellar afforded; for no special stores having been provided for the occasion, there was not half enough bread and cheese for such a multitude. To the rector and his housekeeper, that festival was converted into the most rigid fast-day they had ever observed.

After this signal triumph, the parishioners of Drayton regularly exercised their ‘privilege of Stephening’ till the incumbency of the Rev. Basil Wood, who was presented to the living in 1808. Finding that the custom gave rise to much rioting and drunkenness, he discontinued it, and distributed instead an annual sum of money in proportion to the number of claimants. But as the population of the parish greatly increased, and as he did not consider himself bound to continue the practice, he was induced, about the year 1827, to withhold his annual payments; and so the custom became finally abolished. For some years, however, after its discontinuance, the people used to go to the rectory for the accustomed bounty, but were always refused.

In the year 1834, the commissioners appointed to inquire concerning charities, made an investigation into this custom, and several of the inhabitants of Drayton gave evidence on the occasion, but nothing was elicited to shew its origin or duration, nor was any legal proof advanced skewing that the rector was bound to comply with such a demand. Many of the present inhabitants of the parish remember the custom, and some of them have heard their parents say, that it had been observed:

‘As long as the sun had shone,

And the waters had run.’

In London and other places, St. Stephen’s Day, or the 26th of December, is familiarly known as Boxing-day, from its being the occasion on which those annual guerdons known as Christmas-boxes are solicited and collected. For a notice of them, the reader is referred to the ensuing article.

CHRISTMAS-BOXES

The institution of Christmas-boxes is evidently akin to that of New-year’s gifts, and, like it, has descended to us from the times of the ancient Romans, who, at the season of the Saturnalia, practiced universally the custom of giving and receiving presents. The fathers of the church denounced, on the ground of its pagan origin, the observance of such a usage by the Christians; but their anathemas had little practical effect, and in process of time, the custom of Christmas-boxes and New-year’s gifts, like others adopted from the heathen, attained the position of a universally recognised institution. The church herself has even got the credit of originating the practice of Christmas-boxes, as will appear from the following curious extract from The Athenian Oracle of John Dunton; a sort of primitive Notes and Queries, as it is styled by a contributor to the periodical of that name.

Q. From whence comes the custom of gathering of Christmas-box money? And how long since?

A. It is as ancient as the word mass, which the Romish priests invented from the Latin word mitto, to send, by putting the people in mind to send gifts, offerings, oblations; to have masses said for everything almost, that no ship goes out to the Indies, but the priests have a box in that ship, under the protection of some saint. And for masses, as they cant, to be said for them to that saint, &c., the poor people must put in something into the priest’s box, which is not to be opened till the ship return. Thus the mass at that time was Christ’s-mass, and the box Christ’s-mass-box, or money gathered against that time, that masses might be made by the priests to the saints, to forgive the people the debaucheries of that time; and from this, servants had liberty to get box-money, because they might be enabled to pay the priest for masses –because, No penny, no paternoster– for though the rich pay ten times more than they can expect, yet a priest will not say a mass or anything to the poor for nothing; so charitable they generally are.’

The charity thus ironically ascribed by Dunton to the Roman Catholic clergy, can scarcely, so far as the above extract is concerned, be warrantably claimed by the whimsical author himself. His statement regarding the origin of the custom under notice may be regarded as an ingenious conjecture, but cannot be deemed a satisfactory explanation of the question. As we have already seen, a much greater antiquity and diversity of origin must be asserted.

This custom of Christmas-boxes, or the bestowing of certain expected gratuities at the Christmas season, was formerly, and even yet to a certain extent continues to be, a great nuisance. The journeymen and apprentices of trades-people were wont to levy regular contributions from their masters’ customers, who, in addition, were mulcted by the trades-people in the form of augmented charges in the bills, to recompense the latter for gratuities expected from them by the customers’ servants. This most objectionable usage is now greatly diminished, but certainly cannot yet be said to be extinct. Christmas-boxes are still regularly expected by the postman, the lamplighter, the dustman, and generally by all those functionaries who render services to the public at large, without receiving payment therefore from any particular individual. There is also a very general custom at the Christmas season, of masters presenting their clerks, apprentices, and other employees, with little gifts, either in money or kind.

St. Stephen’s Day, or the 26th of December, being the customary day for the claimants of Christmas-boxes going their rounds, it has received popularly the designation of Boxing-day. In the evening, the new Christmas pantomime for the season is generally produced for the first time; and as the pockets of the working-classes, from the causes which we have above stated, have commonly received an extra supply of funds, the theatres are almost universally crowded to the ceiling on Boxing-night; whilst the ‘gods,’ or upper gallery, exercise even more than their usual authority. Those interested in theatrical matters await with consider-able eagerness the arrival, on the following morning, of the daily papers, which have on this occasion a large space devoted to a chronicle of the pantomimes and spectacles produced at the various London theatres on the previous evening.

In conclusion, we must not be too hard on the system of Christmas-boxes or handsets, as they are termed in Scotland, where, however, they are scarcely ever claimed till after the commencement of the New Year. That many abuses did and still do cling to them, we readily admit; but there is also intermingled with them a spirit of kindliness and benevolence, which it would be very undesirable to extirpate. It seems almost instinctive for the generous side of human nature to bestow some reward for civility and attention, and an additional incentive to such liberality is not infrequently furnished by the belief that its recipient is but inadequately remunerated otherwise for the duties which he performs. Thousands, too, of the commonalty look eagerly forward to the forth-coming guerdon on Boxing-day, as a means of procuring some little unwonted treat or relaxation, either in the way of sight-seeing, or some other mode of enjoyment. Who would desire to abridge the happiness of so many?

06 Dec 2021

St. Nicholas, bishop of Myra, d. 6 December 345 or 352

St. Nicholas was reportedly born in the city of Patara in Lycia in Asia Minor, heir to a wealthy family. He succeeded an uncle as bishop of Myra.

Nicholas left behind a legend of secret acts of benevolence and miracles (in Greek, he is spoken of as “Nikolaos o Thaumaturgos” — Nicholas the Wonder-Worker).

One of the saint’s prominent legends asserts that, in a time of famine, he foiled the crime of Fourth Century Sweeney Todd, an evil butcher who kidnapped and murdered three children, intending to market their remains as ham. St. Nicholas not only exposed the murder, but healed and resurrected the children intact.

Nicholas is also renowned for providing dowries for each of three daughters of an impoverished nobleman,who would otherwise have been unable to marry and who were about to be forced to prostitute themselves to live. In order to spare the sensibilities of the family, Nicholas is said to have secretly thrown a purse of gold coins into their window on each of three consecutive nights.

St. Nicholas’ covert acts of charity led to a custom of the giving of secret gifts concealed in shoes deliberately left out for their receipt on his feast day, and ultimately to the contemporary legend of Santa Claus leaving gifts in stockings on Christmas Eve.

St. Nicholas evolved into one of the most popular saints in the Church’s calendar, serving as patron of sailors, merchants, archers, thieves, prostitutes, pawnbrokers, children, and students, Greeks, Belgians, Frenchmen, Romanians, Bulgarians, Georgians, Albanians, Russians, Macedonians, Slovakians, Serbians, and Montenegrins, and all residents of Aberdeen, Amsterdam, Barranquilla, Campen, Corfu, Freiburg, Liverpool, Lorraine, Moscow, and New Amsterdam (New York).

His relics were stolen and removed to Bari to prevent capture by the Turks, and are alleged to exude a sweet-smelling oil down to the present day.

11 Nov 2021

–An annual post–

WWI came to an end by an armistice arranged to occur at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918. The date and time, selected at a point in history when mens’ memories ran much longer, represented a compliment to St. Martin, patron saint of soldiers, and thus a tribute to the fighting men of both sides. The feast day of St. Martin, the Martinmas, had been for centuries a major landmark in the European calendar, a date on which leases expired, rents came due; and represented, in Northern Europe, a seasonal turning point after which cold weather and snow might be normally expected.

It fell about the Martinmas-time, when the snow lay on the borders…

—Old Song.

From Robert Chambers, The Book of Days, 1869:

St. Martin, the son of a Roman military tribune, was born at Sabaria, in Hungary, about 316. From his earliest infancy, he was remarkable for mildness of disposition; yet he was obliged to become a soldier, a profession most uncongenial to his natural character. After several years’ service, he retired into solitude, from whence he was withdrawn, by being elected bishop of Tours, in the year 374.

The zeal and piety he displayed in this office were most exemplary. He converted the whole of his diocese to Christianity, overthrowing the ancient pagan temples, and erecting churches in their stead. From the great success of his pious endeavours, Martin has been styled the Apostle of the Gauls; and, being the first confessor to whom the Latin Church offered public prayers, he is distinguished as the father of that church. In remembrance of his original profession, he is also frequently denominated the Soldier Saint.

The principal legend, connected with St. Martin, forms the subject of our illustration, which represents the saint, when a soldier, dividing his cloak with a poor naked beggar, whom he found perishing with cold at the gate of Amiens. This cloak, being most miraculously preserved, long formed one of the holiest and most valued relics of France; when war was declared, it was carried before the French monarchs, as a sacred banner, and never failed to assure a certain victory. The oratory in which this cloak or cape—in French, chape—was preserved, acquired, in consequence, the name of chapelle, the person intrusted with its care being termed chapelain: and thus, according to Collin de Plancy, our English words chapel and chaplain are derived. The canons of St. Martin of Tours and St. Gratian had a lawsuit, for sixty years, about a sleeve of this cloak, each claiming it as their property. The Count Larochefoucalt, at last, put an end to the proceedings, by sacrilegiously committing the contested relic to the flames.

Another legend of St. Martin is connected with one of those literary curiosities termed a palindrome. Martin, having occasion to visit Rome, set out to perform the journey thither on foot. Satan, meeting him on the way, taunted the holy man for not using a conveyance more suitable to a bishop. In an instant the saint changed the Old Serpent into a mule, and jumping on its back, trotted comfortably along. Whenever the transformed demon slackened pace, Martin, by making the sign of the cross, urged it to full speed. At last, Satan utterly defeated, exclaimed:

Signa, te Signa: temere me tangis et angis:

Roma tibi subito motibus ibit amor.’

In English—

‘Cross, cross thyself: thou plaguest and vexest me without necessity;

for, owing to my exertions, thou wilt soon reach Rome, the object of thy wishes.’

The singularity of this distich, consists in its being palindromical—that is, the same, whether read backwards or forwards. Angis, the last word of the first line, when read backwards, forming signet, and the other words admitting of being reversed, in a similar manner.

The festival of St. Martin, happening at that season when the new wines of the year are drawn from the lees and tasted, when cattle are killed for winter food, and fat geese are in their prime, is held as a feast-day over most parts of Christendom. On the ancient clog almanacs, the day is marked by the figure of a goose; our bird of Michaelmas being, on the continent, sacrificed at Martinmas. In Scotland and the north of England, a fat ox is called a mart, clearly from Martinmas, the usual time when beeves are killed for winter use. In ‘Tusser’s Husbandry, we read:

When Easter comes, who knows not then,

That veal and bacon is the man?

And Martilmass beef doth bear good tack,

When country folic do dainties lack.’

Barnaby Googe’s translation of Neogeorgus, shews us how Martinmas was kept in Germany, towards the latter part of the fifteenth century

‘To belly chear, yet once again,

Doth Martin more incline,

Whom all the people worshippeth

With roasted geese and wine.

Both all the day long, and the night,

Now each man open makes

His vessels all, and of the must,

Oft times, the last he takes,

Which holy Martin afterwards

Alloweth to be wine,

Therefore they him, unto the skies,

Extol with praise divine.’

A genial saint, like Martin, might naturally be expected to become popular in England; and there are no less than seven churches in London and Westminster, alone, dedicated to him. There is certainly more than a resemblance between the Vinalia of the Romans, and the Martinalia of the medieval period. Indeed, an old ecclesiastical calendar, quoted by Brand, expressly states under 11th November: ‘The Vinalia, a feast of the ancients, removed to this day. Bacchus in the figure of Martin.’ And thus, probably, it happened, that the beggars were taken from St. Martin, and placed under the protection of St. Giles; while the former became the patron saint of publicans, tavern-keepers, and other ‘dispensers of good eating and drinking. In the hall of the Vintners’ Company of London, paintings and statues of St. Martin and Bacchus reign amicably together side by side.

On the inauguration, as lord mayor, of Sir Samuel Dashwood, an honoured vintner, in 1702, the company had a grand processional pageant, the most conspicuous figure in which was their patron saint, Martin, arrayed, cap-Ã -pie, in a magnificent suit of polished armour; wearing a costly scarlet cloak, and mounted on a richly plumed and caparisoned white charger: two esquires, in rich liveries, walking at each side. Twenty satyrs danced before him, beating tambours, and preceded by ten halberdiers, with rural music. Ten Roman lictors, wearing silver helmets, and carrying axes and fasces, gave an air of classical dignity to the procession, and, with the satyrs, sustained the bacchanalian idea of the affair.

A multitude of beggars, ‘howling most lamentably,’ followed the warlike saint, till the procession stopped in St. Paul’s Churchyard. Then Martin, or his representative at least, drawing his sword, cut his rich scarlet cloak in many pieces, which he distributed among the beggars. This ceremony being duly and gravely performed, the lamentable howlings ceased, and the procession resumed its course to Guildhall, where Queen Anne graciously condescended to dine with the new lord mayor.

04 Nov 2021

Samuel John Carter (1835-1892), Legend of St. Hubert, Private Collection (sold December 2007).

Wikipedia:

Saint Hubertus was born (probably in Toulouse) about the year 656. He was the eldest son of Bertrand, Duke of Aquitaine. As a youth, Hubert was sent to the Neustrian court of Theuderic III at Paris, where his charm and agreeable address led to his investment with the dignity of “count of the palace”. Like many nobles of the time, Hubert was addicted to the chase. Meanwhile, the tyrannical conduct of Ebroin, mayor of the Neustrian palace, caused a general emigration of the nobles and others to the court of Austrasia at Metz. Hubert soon followed them and was warmly welcomed by Pepin of Herstal, mayor of the palace, who created him almost immediately grand-master of the household. About this time (682) Hubert married Floribanne, daughter of Dagobert, Count of Leuven.Their son Floribert of Liége would later become bishop of Liége, for bishoprics were all but accounted fiefs heritable in the great families of the Merovingian kingdoms. He nearly died at the age of 10 from “fever”.

His wife died giving birth to their son and Hubert retreated from the court, withdrew into the forested Ardennes, and gave himself up entirely to hunting. However, a great spiritual revolution was imminent. On Good Friday morning, when the faithful were crowding the churches, Hubert sallied forth to the chase. As he was pursuing a magnificent stag or hart, the animal turned and, as the pious legend narrates, he was astounded at perceiving a crucifix standing between its antlers, while he heard a voice saying: “Hubert, unless thou turnest to the Lord, and leadest an holy life, thou shalt quickly go down into hell”. Hubert dismounted, prostrated himself and said, “Lord, what wouldst Thou have me do?” He received the answer, “Go and seek Lambert, and he will instruct you.”…

Saint Hubertus (German) is honored among sport-hunters as the originator of ethical hunting behavior.

During Hubert’s religious vision, the Hirsch (German: deer) is said to have lectured Hubertus into holding animals in higher regard and having compassion for them as God’s creatures with a value in their own right. For example, the hunter ought to only shoot when a humane, clean and quick kill is assured. He ought shoot only old stags past their prime breeding years and to relinquish a much anticipated shot on a trophy to instead euthanize a sick or injured animal that might appear on the scene. Further, one ought never shoot a female with young in tow to assure the young deer have a mother to guide them to food during the winter. Such is the legacy of Hubert who still today is taught and held in high regard in the extensive and rigorous German and Austrian hunter education courses.

The legacy is also followed by the French chasse à courre masters, huntsmen and followers, who hunt deer, boar and roe on horseback and are the last direct heirs of Saint Hubert in Europe. Chasse à courre is currently enjoying a revival in France. The Hunts apply a specific set of ethics, rituals, rules and tactics dating back to the early Middle-Ages. Saint Hubert is venerated every year by the Hunts in formal ceremonies.

——————-

17 Mar 2021

From Robert Chambers, The Book of Days, 1869:

LEGENDARY HISTORY OF ST. PATRICK

Almost as many countries arrogate the honour of having been the natal soil of St. Patrick, as made a similar claim with respect to Homer. Scotland, England, France, and Wales, each furnish their respective pretensions: but, whatever doubts may obscure his birthplace, all agree in stating that, as his name implies, he was of a patrician family. He was born about the year 372, and when only sixteen years of age, was carried off by pirates, who sold him into slavery in Ireland; where his master employed him as a swineherd on the well-known mountain of Sleamish, in the county of Antrim. Here he passed seven years, during which time he acquired a knowledge of the Irish language, and made himself acquainted with the manners, habits, and customs of the people. Escaping from captivity, and, after many adventures, reaching the Continent, he was successively ordained deacon, priest, and bishop: and then once more, with the authority of Pope Celestine, he returned to Ireland to preach the Gospel to its then heathen inhabitants.

The principal enemies that St. Patrick found to the introduction of Christianity into Ireland, were the Druidical priests of the more ancient faith, who, as might naturally be supposed, were exceedingly adverse to any innovation. These Druids, being great magicians, would have been formidable antagonists to any one of less miraculous and saintly powers than Patrick. Their obstinate antagonism was so great, that, in spite of his benevolent disposition, he was compelled to curse their fertile lands, so that they became dreary bogs: to curse their rivers, so that they produced no fish: to curse their very kettles, so that with no amount of fire and patience could they ever be made to boil; and, as a last resort, to curse the Druids themselves, so that the earth opened and swallowed them up. …

The greatest of St. Patrick’s miracles was that of driving the venomous reptiles out of Ireland, and rendering the Irish soil, for ever after, so obnoxious to the serpent race, that they instantaneously die on touching it. Colgan seriously relates that St. Patrick accomplished this feat by beating a drum, which he struck with such fervour that he knocked a hole in it, thereby endangering the success of the miracle. But an angel appearing mended the drum: and the patched instrument was long exhibited as a holy relic. …

When baptizing an Irish chieftain, the venerable saint leaned heavily on his crozier, the steel-spiked point of which he had unwittingly placed on the great toe of the converted heathen. The pious chief, in his ignorance of Christian rites, believing this to be an essential part of the ceremony, bore the pain without flinching or murmur; though the blood flowed so freely from the wound, that the Irish named the place St. fhuil (stream of blood), now pronounced Struill, the name of a well-known place near Downpatrick. And here we are reminded of a very remarkable fact in connection with geographical appellations, that the footsteps of St. Patrick can be traced, almost from his cradle to his grave, by the names of places called after him.

Thus, assuming his Scottish origin, he was born at Kilpatrick (the cell or church of Patrick), in Dumbartonshire. He resided for some time at Dalpatrick (the district or division of Patrick), in Lanarkshire; and visited Crag-phadrig (the rock of Patrick), near Inverness. He founded two churches, Kirkpatrick at Irongray, in Kireudbright; and Kirkpatrick at Fleming, in Dumfries: and ultimately sailed from Portpatrick, leaving behind him such an odour of sanctity, that among the most distinguished families of the Scottish aristocracy, Patrick has been a favourite name down to the present day.

Arriving in England, he preached in Patterdale (Patrick’s dale), in Westmoreland: and founded the church of Kirkpatrick, in Durham. Visiting Wales, he walked over Sarn-badrig (Patrick’s causeway), which, now covered by the sea, forms a dangerous shoal in Carnarvon Bay: and departing for the Continent, sailed from Llan-badrig (the church of Patrick), in the island of Anglesea. Undertaking his mission to convert the Irish, he first landed at Innis-patrick (the island of Patrick), and next at Holmpatrick, on the opposite shore of the mainland, in the county of Dublin. Sailing northwards, he touched at the Isle of Man, sometimes since, also, called. Innis-patrick, where he founded another church of Kirkpatrick, near the town of Peel. Again landing on the coast of Ireland, in the county of Down, he converted and baptized the chieftain Dichu, on his own threshing-floor. The name of the parish of Saul, derived from Sabbal-patrick (the barn of Patrick), perpetuates the event. He then proceeded to Temple-patrick, in Antrim, and from thence to a lofty mountain in Mayo, ever since called Croagh-patrick.

He founded an abbey in East Meath, called Domnach-Padraig (the house of Patrick), and built a church in Dublin on the spot where St. Patrick’s Cathedral now stands. In an island of Lough Deng, in the county of Donegal, there is St. Patrick’s Purgatory: in Leinster, St. Patrick’s Wood; at Cashel, St. Patrick’s Rock; the St. Patrick’s Wells, at which the holy man is said to have quenched his thirst, may be counted by dozens. He is commonly stated to have died at Saul on the 17th of March 493, in the one hundred and twenty-first year of his age. …

The shamrock, or small white clover (trifolium repens of botanists), is almost universally worn in the hat over all Ireland, on St. Patrick’s day. The popular notion is, that when St. Patrick was preaching the doctrine of the Trinity to the pagan Irish, he used this plant, bearing three leaves upon one stem, as a symbol or illustration of the great mystery. To suppose, as some absurdly hold, that he used it as an argument, would be derogatory to the saint’s high reputation for orthodoxy and good sense: but it is certainly a curious coincidence, if nothing more, that the trefoil in Arabic is called skamrakh, and was held sacred in Iran as emblematical of the Persian Triads. Pliny, too, in his Natural History, says that serpents are never seen upon trefoil, and it prevails against the stings of snakes and scorpions. This, considering St. Patrick’s connexion with snakes, is really remarkable, and we may reasonably imagine that, previous to his arrival, the Irish had ascribed mystical virtues to the trefoil or shamrock, and on hearing of the Trinity for the first time, they fancied some peculiar fitness in their already sacred plant to shadow forth the newly revealed and mysterious doctrine. …

In the Galtee or Gaultie Mountains, situated between the counties of Cork and Tipperary, there are seven lakes, in one of which, called Lough Dilveen, it is said Saint Patrick, when banishing the snakes and toads from Ireland, chained a monster serpent, telling him to remain there till Monday.

The serpent every Monday morning calls out in Irish, ‘It is a long Monday, Patrick.’

That St Patrick chained the serpent in Lough Dilveen, and that the serpent calls out to him every Monday morning, is firmly believed by the lower orders who live in the neighbourhood of the Lough.

14 Feb 2021

Jacopo Bassano, St Valentine Baptizing St Lucilla, 1575, oil on canvas, Museo Civico, Bassano del Grappa

The popular customs associated with Saint Valentine’s Day undoubtedly had their origin in a conventional belief generally received in England and France during the Middle Ages, that on 14 February, i.e., half way through the second month of the year, the birds began to pair. Thus in Chaucer’s Parliament of Foules we read:

For this was sent on Seynt Valentyne’s day

Whan every foul cometh ther to choose his mate.

For this reason the day was looked upon as specially consecrated to lovers and as a proper occasion for writing love letters and sending lovers’ tokens. Both the French and English literatures of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries contain allusions to the practice. Perhaps the earliest to be found is in the 34th and 35th Ballades of the bilingual poet, John Gower, written in French; but Lydgate and Clauvowe supply other examples. Those who chose each other under these circumstances seem to have been called by each other their Valentines.

In the Paston Letters, Dame Elizabeth Brews writes thus about a match she hopes to make for her daughter (we modernize the spelling), addressing the favoured suitor:

And, cousin mine, upon Monday is Saint Valentine’s Day and every bird chooses himself a mate, and if it like you to come on Thursday night, and make provision that you may abide till then, I trust to God that ye shall speak to my husband and I shall pray that we may bring the matter to a conclusion.

——————————————–

From Robert Chambers, The Book of Days, 1869: Feast Day: St. Valentine, priest and martyr, circ. 270.

ST. VALENTINE’S DAY

Valentine’s Day is now almost everywhere a much degenerated festival, the only observance of any note consisting merely of the sending of jocular anonymous letters to parties whom one wishes to quiz, and this confined very much to the humbler classes. The approach of the day is now heralded by the appearance in the print-sellers’ shop windows of vast numbers of missives calculated for use on this occasion, each generally consisting of a single sheet of post paper, on the first page of which is seen some ridiculous coloured caricature of the male or female figure, with a few burlesque verses below. More rarely, the print is of a sentimental kind, such as a view of Hymen’s altar, with a pair undergoing initiation into wedded happiness before it, while Cupid flutters above, and hearts transfixed with his darts decorate the corners. Maid-servants and young fellows interchange such epistles with each other on the 14th of February, no doubt conceiving that the joke is amazingly good: and, generally, the newspapers do not fail to record that the London postmen delivered so many hundred thousand more letters on that day than they do in general. Such is nearly the whole extent of the observances now peculiar to St. Valentine’s Day.

At no remote period it was very different. Ridiculous letters were unknown: and, if letters of any kind were sent, they contained only a courteous profession of attachment from some young man to some young maiden, honeyed with a few compliments to her various perfections, and expressive of a hope that his love might meet with return. But the true proper ceremony of St. Valentine’s Day was the drawing of a kind of lottery, followed by ceremonies not much unlike what is generally called the game of forfeits. Misson, a learned traveller, of the early part of the last century, gives apparently a correct account of the principal ceremonial of the day.

‘On the eve of St. Valentine’s Day,’ he says, ‘the young folks in England and Scotland, by a very ancient custom, celebrate a little festival. An equal number of maids and bachelors get together: each writes their true or some feigned name upon separate billets, which they roll up, and draw by way of lots, the maids taking the men’s billets, and the men the maids’: so that each of the young men lights upon a girl that he calls his valentine, and each of the girls upon a young man whom she calls hers. By this means each has two valentines: but the man sticks faster to the valentine that has fallen to him than to the valentine to whom he is fallen. Fortune having thus divided the company into so many couples, the valentines give balls and treats to their mistresses, wear their billets several days upon their bosoms or sleeves, and this little sport often ends in love.’

St. Valentine’s Day is alluded to by Shakespeare and by Chaucer, and also by the poet Lydgate (who died in 1440).

The origin of these peculiar observances of St. Valentine’s Day is a subject of some obscurity. The saint himself, who was a priest of Rome, martyred in the third century, seems to have had nothing to do with the matter, beyond the accident of his day being used for the purpose. Mr. Douce, in his Illustrations of Shakespeare, says:

“It was the practice in ancient Rome, during a great part of the month of February, to celebrate the Lupercalia, which were feasts in honour of Pan and Juno. whence the latter deity was named Februata, Februalis, and Februlla. On this occasion, amidst a variety of ceremonies, the names of young women were put into a box, from which they were drawn by the men as chance directed. The pastors of the early Christian church, who, by every possible means, endeavoured to eradicate the vestiges of pagan superstitions, and chiefly by some commutations of their forms, substituted, in the present instance, the names of particular saints instead of those of the women: and as the festival of the Lupercalia had commenced about the middle of February, they appear to have chosen St. Valentine’s Day for celebrating the new feast, because it occurred nearly at the same time.”

—————————————————-

February 14th, prior to 1969, was the feast day of two, or possibly three, saints and martyrs named Valentine, all reputedly of the Third Century.

The first Valentine, legend holds, was a physician and priest in Rome, arrested for giving aid to martyrs in prison, who while there converted his jailer by restoring sight to the jailer’s daughter. He was executed by being beaten with clubs, and afterwards beheaded, February 14, 270. He is traditionally the patron of affianced couples, bee keepers, lovers, travellers, young people, and greeting card manufacturers, and his special assistance may be sought in conection with epilepsy, fainting, and plague.

A second St. Valentine, reportedly bishop of Interamna (modern Terni) was also allegedly martyred under Claudius II, and also allegedly buried along the Flaminian Way.

A third St. Valentine is said to have also been martyred in Roman times, along with companions, in Africa.

Due to an insufficiency of historical evidence in the eyes of Vatican II modernizers, the Roman Catholic Church dropped the February 14th feast of St. Valentine from its calendar in 1969.

26 Dec 2020

Rembrandt. The Martyrdom of St. Stephen. 1625. Oil on panel. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyons

From Robert Chambers, The Book of Days, 1869:

Feast Day: St. Stephen, the first martyr.

St. Stephen’s Day

To St. Stephen, the Proto-martyr, as he is generally styled, the honour has been accorded by the church of being placed in her calendar immediately after Christmas-day, in recognition of his having been the first to seal with his blood the testimony of fidelity to his Lord and Master. The year in which he was stoned to death, as recorded in the Acts of the Apostles, is supposed to have been 33 A.D. The festival commemorative of him has been retained in the Anglican calendar.

A curious superstition was formerly prevalent regarding St. Stephen’s Day — that horses should then, after being first well galloped, be copiously let blood, to insure them against disease in the course of the following year. In Barnaby Googe’s translation of Naogeorgus, the following lines occur relative to this popular notion:

Then followeth Saint Stephen’s Day, whereon doth every man

His horses jaunt and course abrode, as swiftly as he can,

Until they doe extremely sweate, and then they let them blood,

For this being done upon this day, they say doth do them good,

And keepes them from all maladies and sicknesse through the yeare,

As if that Steven any time tooke charge of horses heare.’

The origin of this practice is difficult to be accounted for, but it appears to be very ancient, and Douce supposes that it was introduced into this country by the Danes. In one of the manuscripts of that interesting chronicler, John Aubrey, who lived in the latter half of the seventeenth century, occurs the following record: On St. Stephen’s Day, the farrier came constantly and blouded all our cart-horses.’ Very possibly convenience and expediency combined on the occasion with superstition, for in Tusser Redivivus, a work published in the middle of the last century, we find this statement: ‘About Christmas is a very proper time to bleed horses in, for then they are commonly at house, then spring comes on, the sun being now coming back from the winter-solstice, and there are three or four days of rest, and if it be upon St. Stephen’s Day it is not the worse, seeing there are with it three days of rest, or at least two.’

In the parish of Drayton Beauchamp, Bucks, there existed long an ancient custom, called Stephening, from the day on which it took place. On St. Stephen’s Day, all the inhabitants used to pay a visit to the rectory, and practically assert their right to partake of as much bread and cheese and ale as they chose at the rector’s expense. On one of these occasions, according to local tradition, the then rector, being a penurious old bachelor, determined to put a stop, if possible, to this rather expensive and unceremonious visit from his parishioners. Accordingly, when St. Stephen’s Day arrived, he ordered his housekeeper not to open the window-shutters, or unlock the doors of the house, and to remain perfectly silent and motionless whenever any person was heard approaching. At the usual time the parishioners began to cluster about the house. They knocked first at one door, then at the other, then tried to open them, and on finding them fastened, they called aloud for admittance. No voice replied. No movement was heard within. ‘Surely the rector and his house-keeper must both be dead!’ exclaimed several voices at once, and a general awe pervaded the whole group. Eyes were then applied to the key-holes, and to every crevice in the window-shutters, when the rector was seen beckoning his old terrified housekeeper to sit still and silent. A simultaneous shout convinced him that his design was understood. Still he consoled himself with the hope that his larder and his cellar were secure, as the house could not be entered. But his hope was speedily dissipated. Ladders were reared against the roof, tiles were hastily thrown off, half-a-dozen sturdy young men entered, rushed down the stairs, and threw open both the outer-doors. In a trice, a hundred or more unwelcome visitors rushed into the house, and began unceremoniously to help themselves to such fare as the larder and cellar afforded; for no special stores having been provided for the occasion, there was not half enough bread and cheese for such a multitude. To the rector and his housekeeper, that festival was converted into the most rigid fast-day they had ever observed.

After this signal triumph, the parishioners of Drayton regularly exercised their ‘privilege of Stephening’ till the incumbency of the Rev. Basil Wood, who was presented to the living in 1808. Finding that the custom gave rise to much rioting and drunkenness, he discontinued it, and distributed instead an annual sum of money in proportion to the number of claimants. But as the population of the parish greatly increased, and as he did not consider himself bound to continue the practice, he was induced, about the year 1827, to withhold his annual payments; and so the custom became finally abolished. For some years, however, after its discontinuance, the people used to go to the rectory for the accustomed bounty, but were always refused.

In the year 1834, the commissioners appointed to inquire concerning charities, made an investigation into this custom, and several of the inhabitants of Drayton gave evidence on the occasion, but nothing was elicited to shew its origin or duration, nor was any legal proof advanced skewing that the rector was bound to comply with such a demand. Many of the present inhabitants of the parish remember the custom, and some of them have heard their parents say, that it had been observed:

‘As long as the sun had shone,

And the waters had run.’

In London and other places, St. Stephen’s Day, or the 26th of December, is familiarly known as Boxing-day, from its being the occasion on which those annual guerdons known as Christmas-boxes are solicited and collected. For a notice of them, the reader is referred to the ensuing article.

CHRISTMAS-BOXES

The institution of Christmas-boxes is evidently akin to that of New-year’s gifts, and, like it, has descended to us from the times of the ancient Romans, who, at the season of the Saturnalia, practiced universally the custom of giving and receiving presents. The fathers of the church denounced, on the ground of its pagan origin, the observance of such a usage by the Christians; but their anathemas had little practical effect, and in process of time, the custom of Christmas-boxes and New-year’s gifts, like others adopted from the heathen, attained the position of a universally recognised institution. The church herself has even got the credit of originating the practice of Christmas-boxes, as will appear from the following curious extract from The Athenian Oracle of John Dunton; a sort of primitive Notes and Queries, as it is styled by a contributor to the periodical of that name.

Q. From whence comes the custom of gathering of Christmas-box money? And how long since?

A. It is as ancient as the word mass, which the Romish priests invented from the Latin word mitto, to send, by putting the people in mind to send gifts, offerings, oblations; to have masses said for everything almost, that no ship goes out to the Indies, but the priests have a box in that ship, under the protection of some saint. And for masses, as they cant, to be said for them to that saint, &c., the poor people must put in something into the priest’s box, which is not to be opened till the ship return. Thus the mass at that time was Christ’s-mass, and the box Christ’s-mass-box, or money gathered against that time, that masses might be made by the priests to the saints, to forgive the people the debaucheries of that time; and from this, servants had liberty to get box-money, because they might be enabled to pay the priest for masses –because, No penny, no paternoster– for though the rich pay ten times more than they can expect, yet a priest will not say a mass or anything to the poor for nothing; so charitable they generally are.’

The charity thus ironically ascribed by Dunton to the Roman Catholic clergy, can scarcely, so far as the above extract is concerned, be warrantably claimed by the whimsical author himself. His statement regarding the origin of the custom under notice may be regarded as an ingenious conjecture, but cannot be deemed a satisfactory explanation of the question. As we have already seen, a much greater antiquity and diversity of origin must be asserted.

This custom of Christmas-boxes, or the bestowing of certain expected gratuities at the Christmas season, was formerly, and even yet to a certain extent continues to be, a great nuisance. The journeymen and apprentices of trades-people were wont to levy regular contributions from their masters’ customers, who, in addition, were mulcted by the trades-people in the form of augmented charges in the bills, to recompense the latter for gratuities expected from them by the customers’ servants. This most objectionable usage is now greatly diminished, but certainly cannot yet be said to be extinct. Christmas-boxes are still regularly expected by the postman, the lamplighter, the dustman, and generally by all those functionaries who render services to the public at large, without receiving payment therefore from any particular individual. There is also a very general custom at the Christmas season, of masters presenting their clerks, apprentices, and other employees, with little gifts, either in money or kind.

St. Stephen’s Day, or the 26th of December, being the customary day for the claimants of Christmas-boxes going their rounds, it has received popularly the designation of Boxing-day. In the evening, the new Christmas pantomime for the season is generally produced for the first time; and as the pockets of the working-classes, from the causes which we have above stated, have commonly received an extra supply of funds, the theatres are almost universally crowded to the ceiling on Boxing-night; whilst the ‘gods,’ or upper gallery, exercise even more than their usual authority. Those interested in theatrical matters await with consider-able eagerness the arrival, on the following morning, of the daily papers, which have on this occasion a large space devoted to a chronicle of the pantomimes and spectacles produced at the various London theatres on the previous evening.

In conclusion, we must not be too hard on the system of Christmas-boxes or handsets, as they are termed in Scotland, where, however, they are scarcely ever claimed till after the commencement of the New Year. That many abuses did and still do cling to them, we readily admit; but there is also intermingled with them a spirit of kindliness and benevolence, which it would be very undesirable to extirpate. It seems almost instinctive for the generous side of human nature to bestow some reward for civility and attention, and an additional incentive to such liberality is not infrequently furnished by the belief that its recipient is but inadequately remunerated otherwise for the duties which he performs. Thousands, too, of the commonalty look eagerly forward to the forth-coming guerdon on Boxing-day, as a means of procuring some little unwonted treat or relaxation, either in the way of sight-seeing, or some other mode of enjoyment. Who would desire to abridge the happiness of so many?

06 Dec 2020

St. Nicholas, bishop of Myra, d. 6 December 345 or 352

St. Nicholas was reportedly born in the city of Patara in Lycia in Asia Minor, heir to a wealthy family. He succeeded an uncle as bishop of Myra.

Nicholas left behind a legend of secret acts of benevolence and miracles (in Greek, he is spoken of as “Nikolaos o Thaumaturgos” — Nicholas the Wonder-Worker).

One of the saint’s prominent legends asserts that, in a time of famine, he foiled the crime of Fourth Century Sweeney Todd, an evil butcher who kidnapped and murdered three children, intending to market their remains as ham. St. Nicholas not only exposed the murder, but healed and resurrected the children intact.

Nicholas is also renowned for providing dowries for each of three daughters of an impoverished nobleman,who would otherwise have been unable to marry and who were about to be forced to prostitute themselves to live. In order to spare the sensibilities of the family, Nicholas is said to have secretly thrown a purse of gold coins into their window on each of three consecutive nights.

St. Nicholas’ covert acts of charity led to a custom of the giving of secret gifts concealed in shoes deliberately left out for their receipt on his feast day, and ultimately to the contemporary legend of Santa Claus leaving gifts in stockings on Christmas Eve.

St. Nicholas evolved into one of the most popular saints in the Church’s calendar, serving as patron of sailors, merchants, archers, thieves, prostitutes, pawnbrokers, children, and students, Greeks, Belgians, Frenchmen, Romanians, Bulgarians, Georgians, Albanians, Russians, Macedonians, Slovakians, Serbians, and Montenegrins, and all residents of Aberdeen, Amsterdam, Barranquilla, Campen, Corfu, Freiburg, Liverpool, Lorraine, Moscow, and New Amsterdam (New York).

His relics were stolen and removed to Bari to prevent capture by the Turks, and are alleged to exude a sweet-smelling oil down to the present day.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Hagiography' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|