“Innovation”

Innovation, Language

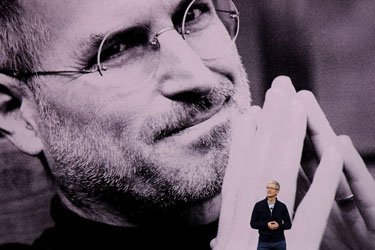

Apple CEO Tim Cook speaks during an Apple special event at the Steve Jobs Theatre on the Apple Park campus on September 12, 2017 in Cupertino, California.

Amusingly, leftist English prof John Patrick Leary, writing in Jacobin, sounds a lot like Edmund Burke or Pope Pius X when he’s denouncing popular contemporary cant about “innovation.”

For most of its early life, the word “innovation†was a pejorative, used to denounce false prophets and political dissidents. Thomas Hobbes used innovator in the seventeenth century as a synonym for a vain conspirator; Edmund Burke decried the innovators of revolutionary Paris as wreckers and miscreants; in 1837, a Catholic priest in Vermont devoted 320 pages to denouncing “the Innovator,†an archetypal heretic he summarized as an “infidel and a sceptick at heart.†The innovator’s skepticism was a destructive conspiracy against the established order, whether in heaven or on Earth. And if the innovator styled himself a seer, he was a false prophet.

By the turn of the last century, though, the practice of innovation had begun to shed these associations with plotting and heresy. A milestone may have been achieved around 1914, when Vernon Castle, America’s foremost dance instructor, invented a “decent,†simplified American version of the Argentine tango and named it “the Innovation.â€

“We are now in a state of transmission to more beautiful dancing,†said Mamie Fish, the famed New York socialite credited with naming the dance. She told the Omaha Bee in 1914 that “this latest is a remarkably pretty dance, lacking in all the eccentricities and abandon of the ‘tango,’ and it is not at all difficult to do.†No longer a deviant sin, innovation — and “The Innovation†— had become positively decent.

The contemporary ubiquity of innovation is an example of how the world of business, despite its claims of rationality and empirical precision, also summons its own enigmatic mythologies. Many of the words covered in my new book, Keywords, orbit this one, deriving their own authority from their connection to the power of innovation.

The value of innovation is so widespread and so seemingly self-evident that questioning it might seem bizarre — like criticizing beauty, science, or penicillin, things that are, like innovation, treated as either abstract human values or socially useful things we can scarcely imagine doing without. And certainly, many things called innovations are, in fact, innovative in the strict sense: original processes or products that satisfy some human need.

A scholar can uncover archival evidence that transforms how we understand the meaning of a historical event; an automotive engineer can develop new industrial processes to make a car lighter; a corporate executive can extract additional value from his employees by automating production. These are all new ways of doing something, but they are very different somethings. Some require a combination of dogged persistence and interpretive imagination; others make use of mathematical and technical expertise; others, organizational vision and practical ruthlessness.

But innovation as it is used most often today comes with an implied sense of benevolence; we rarely talk of innovative credit-default swaps or innovative chemical weapons, but innovations they plainly are. The destructive skepticism of the false-prophet innovator has been redeemed as the profit-making insight of the technological visionary.

Innovation is most popular today as a stand-alone concept, a kind of managerial spirit that permeates nearly every institutional setting, from nonprofits and newspapers to schools and children’s toys. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines innovation as “the alteration of what is established by the introduction of new elements or forms.†The earliest example the dictionary gives dates from the mid-sixteenth century; the adjectival “innovative,†meanwhile, was virtually unknown before the 1960s, but has exploded in popularity since.

The verb “to innovate†has also seen a resurgence in recent years. The verb’s intransitive meaning is “to bring in or introduce novelties; to make changes in something established; to introduce innovations.†Its earlier transitive meaning, “To change (a thing) into something new; to alter; to renew†is considered obsolete by the OED, but this meaning has seen something of a revival. This was the active meaning associated with conspirators and heretics, who were innovating the word of God or innovating government, in the sense of undermining or overthrowing each.

The major conflict in innovation’s history is that between its formerly prohibited, religious connotation and the salutary, practical meaning that predominates now. Benoît Godin has shown that innovation was recuperated as a secular concept in the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth, when it became a form of worldly praxis rather than theological reflection. Its grammar evolved along with this meaning. Instead of a discrete irruption in an established order, innovation as a mass noun became a visionary faculty that individuals could nurture and develop in practical ways in the world; it was also the process of applying this faculty (e.g., “Lenovo’s pursuit of innovationâ€).