Cornell Prof Has Good News For Us Hicks

Economic Reality, Small Towns, The Elect, The Elite, The Experts, The Internet, Time and Change

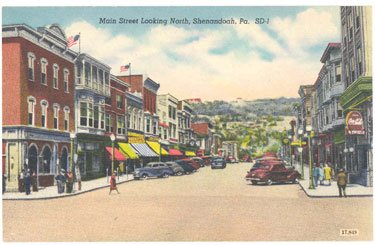

North Main Street, Shenandoah, Pennsylvania, just a bit before my time. It still looked just like this when I was a boy.

Cornell Economic historian Louis Hyman strokes his chin in the New York Times, points out to the rest of us peons the economic realities that everybody already knows, and then assures Red State Trump supporters who prefer small towns to the metropolis that they can do just fine after all.

We need merely get used to doing without buildings, streets, theaters, bars, and churches, and make ourselves comfortable in electronic neighborhoods on Internet social media, while making a good living marketing our quaint custom handicrafts to the international luxury market on-line.

Isn’t it easy to solve these things from your departmental office at Cornell?

Throughout the Rust Belt and much of rural America, the image of Main Street is one of empty storefronts and abandoned buildings interspersed with fast-food franchises, only a short drive from a Walmart.

Main Street is a place but it is also an idea. It’s small-town retail. It’s locally owned shops selling products to hardworking townspeople. It’s neighbors with dependable blue-collar jobs in auto plants and coal mines. It’s a feeling of community and of having control over your life. It’s everything, in short, that seems threatened by global capitalism and cosmopolitan elites in big cities and fancy suburbs.

Mr. Trump’s campaign slogan was “Make America Great Again,†but it could just as easily have been “Bring Main Street Back.†Since taking office, he has signed an executive order designed to revive the coal industry, promised a $1 trillion infrastructure bill and continued to express support for tariffs and to criticize globalism and international free trade. “The jobs and wealth have been stripped from our country,†he said last month, signing executive orders meant to improve the trade deficit. “We’re bringing manufacturing and jobs back.â€

But nostalgia for Main Street is misplaced — and costly. Small stores are inefficient. Local manufacturers, lacking access to economies of scale, usually are inefficient as well. To live in that kind of world is expensive.

This nostalgia, like the frustration that underlies it, has a long and instructive history. Years before deindustrialization, years before Nafta, Americans were yearning for a Main Street that never quite existed. . . . The fight to save Main Street, then as now, was less about the price of goods gained than the cost of autonomy lost. . . .

To save Main Street, state lawmakers in the 1930s passed “fair trade†legislation that set floors for retail prices, protecting small-town manufacturers and retailers from big business’s economies of scale. These laws permitted manufacturers to dictate prices for their products in a state (which is where that now-meaningless phrase “manufacturer’s suggested retail price†comes from); if a manufacturer had a price agreement with even one retailer in a state, other stores in the state could not discount that product. As a result, chain stores could no longer demand a lower price from manufacturers, despite buying in higher volumes.

These laws allowed Main Street shops to somewhat compete with chain stores, and kept prices (and profits) higher than a truly free market would have allowed. At the same time, workers, empowered by the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, organized the A. & P. and other chain stores, as well as these buttressed Main Street manufacturers, so that they also got a share of the profits. Main Street — its owners and its workers — was kept afloat, but at a cost to consumers, for whom prices remained high.

But this world was unsustainable. It unraveled in the 1960s and 1970s, as fair trade laws were repealed, manufacturers discovered overseas suppliers and unions came undone. On Main Street, prices came down for shoppers, but at the same time, so did wage growth. Main Street was officially dead.

It’s worth noting that the idealized Main Street is not a myth in some parts of America today. It exists, but only as a luxury consumer experience. Main Streets of small, independent boutiques and nonfranchised restaurants can be found in affluent college towns, in gentrified neighborhoods in Brooklyn and San Francisco, in tony suburbs — in any place where people have ample disposable income. Main Street requires shoppers who don’t really care about low prices. The dream of Main Street may be populist, but the reality is elitist. “Keep it local†campaigns are possible only when people are willing and able to pay to do so.

In hard-pressed rural communities and small towns, that isn’t an option. This is why the nostalgia for Main Street is so harmful: It raises false hopes, which when dashed fuel anger and despair. President Trump’s promises notwithstanding, there is no going back to an economic arrangement whose foundations were so shaky. In the long run, American capitalism cannot remain isolated from the global economy. To do so would be not only stultifying for Americans, but also perilous for the rest of the world’s economic growth, with all the attendant political dangers. …

Many rural Americans, sadly, don’t realize how valuable they already are or what opportunities presently exist for them. It’s true that the digital economy, centered in a few high-tech cities, has left Main Street America behind. But it does not need to be this way. Today, for the first time, thanks to the internet, small-town America can pull back money from Wall Street (and big cities more generally). Through global freelancing platforms like Upwork, for example, rural and small-town Americans can find jobs anywhere in world, using abilities and talents they already have. A receptionist can welcome office visitors in San Francisco from her home in New York’s Finger Lakes. Through an e-commerce website like Etsy, an Appalachian woodworker can create custom pieces and sell them anywhere in the world.

Americans, regardless of education or geographical location, have marketable skills in the global economy: They speak English and understand the nuances of communicating with Americans — something that cannot be easily shipped overseas. The United States remains the largest consumer market in the world, and Americans can (and some already do) sell these services abroad.