St. Patrick’s Day

Hagiography, History, St. Patrick, St. Patrick's Day, Traditions

From Robert Chambers, The Book of Days, 1869:

LEGENDARY HISTORY OF ST. PATRICK

Almost as many countries arrogate the honour of having been the natal soil of St. Patrick, as made a similar claim with respect to Homer. Scotland, England, France, and Wales, each furnish their respective pretensions: but, whatever doubts may obscure his birthplace, all agree in stating that, as his name implies, he was of a patrician family. He was born about the year 372, and when only sixteen years of age, was carried off by pirates, who sold him into slavery in Ireland; where his master employed him as a swineherd on the well-known mountain of Sleamish, in the county of Antrim. Here he passed seven years, during which time he acquired a knowledge of the Irish language, and made himself acquainted with the manners, habits, and customs of the people. Escaping from captivity, and, after many adventures, reaching the Continent, he was successively ordained deacon, priest, and bishop: and then once more, with the authority of Pope Celestine, he returned to Ireland to preach the Gospel to its then heathen inhabitants.

The principal enemies that St. Patrick found to the introduction of Christianity into Ireland, were the Druidical priests of the more ancient faith, who, as might naturally be supposed, were exceedingly adverse to any innovation. These Druids, being great magicians, would have been formidable antagonists to any one of less miraculous and saintly powers than Patrick. Their obstinate antagonism was so great, that, in spite of his benevolent disposition, he was compelled to curse their fertile lands, so that they became dreary bogs: to curse their rivers, so that they produced no fish: to curse their very kettles, so that with no amount of fire and patience could they ever be made to boil; and, as a last resort, to curse the Druids themselves, so that the earth opened and swallowed them up. …

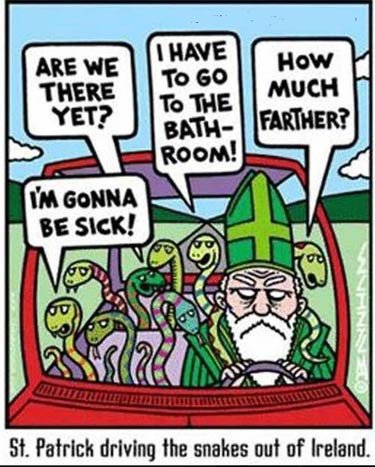

The greatest of St. Patrick’s miracles was that of driving the venomous reptiles out of Ireland, and rendering the Irish soil, for ever after, so obnoxious to the serpent race, that they instantaneously die on touching it. Colgan seriously relates that St. Patrick accomplished this feat by beating a drum, which he struck with such fervour that he knocked a hole in it, thereby endangering the success of the miracle. But an angel appearing mended the drum: and the patched instrument was long exhibited as a holy relic. …

When baptizing an Irish chieftain, the venerable saint leaned heavily on his crozier, the steel-spiked point of which he had unwittingly placed on the great toe of the converted heathen. The pious chief, in his ignorance of Christian rites, believing this to be an essential part of the ceremony, bore the pain without flinching or murmur; though the blood flowed so freely from the wound, that the Irish named the place St. fhuil (stream of blood), now pronounced Struill, the name of a well-known place near Downpatrick. And here we are reminded of a very remarkable fact in connection with geographical appellations, that the footsteps of St. Patrick can be traced, almost from his cradle to his grave, by the names of places called after him.

Thus, assuming his Scottish origin, he was born at Kilpatrick (the cell or church of Patrick), in Dumbartonshire. He resided for some time at Dalpatrick (the district or division of Patrick), in Lanarkshire; and visited Crag-phadrig (the rock of Patrick), near Inverness. He founded two churches, Kirkpatrick at Irongray, in Kireudbright; and Kirkpatrick at Fleming, in Dumfries: and ultimately sailed from Portpatrick, leaving behind him such an odour of sanctity, that among the most distinguished families of the Scottish aristocracy, Patrick has been a favourite name down to the present day.

Arriving in England, he preached in Patterdale (Patrick’s dale), in Westmoreland: and founded the church of Kirkpatrick, in Durham. Visiting Wales, he walked over Sarn-badrig (Patrick’s causeway), which, now covered by the sea, forms a dangerous shoal in Carnarvon Bay: and departing for the Continent, sailed from Llan-badrig (the church of Patrick), in the island of Anglesea. Undertaking his mission to convert the Irish, he first landed at Innis-patrick (the island of Patrick), and next at Holmpatrick, on the opposite shore of the mainland, in the county of Dublin. Sailing northwards, he touched at the Isle of Man, sometimes since, also, called. Innis-patrick, where he founded another church of Kirkpatrick, near the town of Peel. Again landing on the coast of Ireland, in the county of Down, he converted and baptized the chieftain Dichu, on his own threshing-floor. The name of the parish of Saul, derived from Sabbal-patrick (the barn of Patrick), perpetuates the event. He then proceeded to Temple-patrick, in Antrim, and from thence to a lofty mountain in Mayo, ever since called Croagh-patrick.

He founded an abbey in East Meath, called Domnach-Padraig (the house of Patrick), and built a church in Dublin on the spot where St. Patrick’s Cathedral now stands. In an island of Lough Deng, in the county of Donegal, there is St. Patrick’s Purgatory: in Leinster, St. Patrick’s Wood; at Cashel, St. Patrick’s Rock; the St. Patrick’s Wells, at which the holy man is said to have quenched his thirst, may be counted by dozens. He is commonly stated to have died at Saul on the 17th of March 493, in the one hundred and twenty-first year of his age.

Poteen, a favourite beverage in Ireland, is also said to have derived its name from St. Patrick: he, according to legend, being the first who instructed the Irish in the art of distillation. This, however, is, to say the least, doubtful: the most authentic historians representing the saint as a very strict promoter of temperance, if not exactly a teetotaller. We read that in 445 he commanded his disciples to abstain from drink in the day-time, until the bell rang for vespers in the evening. One Colman, though busily engaged in the severe labours of the field, exhausted with heat, fatigue, and intolerable thirst, obeyed so literally the injunction of his revered preceptor, that he refrained from indulging himself with one drop of water during a long sultry harvest day. But human endurance has its limits: when the vesper bell at last rang for evensong, Colman dropped down dead—a martyr to thirst. Irishmen can well appreciate such a martyrdom; and the name of Colman, to this day, is frequently cited, with the added epithet of Shadhack—the Thirsty.

-

‘In Burgo Duno, tumulo tumulantur in uno,

Brigida, Patricius, atque Columba pins.’

Which may be thus rendered:

-

‘In the hill of Down, buried in one tomb,

Were Bridget and Patricius, with Columba the pious.’

The shamrock, or small white clover (trifolium repens of botanists), is almost universally worn in the hat over all Ireland, on St. Patrick’s day. The popular notion is, that when St. Patrick was preaching the doctrine of the Trinity to the pagan Irish, he used this plant, bearing three leaves upon one stem, as a symbol or illustration of the great mystery. To suppose, as some absurdly hold, that he used it as an argument, would be derogatory to the saint’s high reputation for orthodoxy and good sense: but it is certainly a curious coincidence, if nothing more, that the trefoil in Arabic is called skamrakh, and was held sacred in Iran as emblematical of the Persian Triads. Pliny, too, in his Natural History, says that serpents are never seen upon trefoil, and it prevails against the stings of snakes and scorpions. This, considering St. Patrick’s connexion with snakes, is really remarkable, and we may reasonably imagine that, previous to his arrival, the Irish had ascribed mystical virtues to the trefoil or shamrock, and on hearing of the Trinity for the first time, they fancied some peculiar fitness in their already sacred plant to shadow forth the newly revealed and mysterious doctrine. …

In the Galtee or Gaultie Mountains, situated between the counties of Cork and Tipperary, there are seven lakes, in one of which, called Lough Dilveen, it is said Saint Patrick, when banishing the snakes and toads from Ireland, chained a monster serpent, telling him to remain there till Monday.

The serpent every Monday morning calls out in Irish, ‘It is a long Monday, Patrick.’

That St Patrick chained the serpent in Lough Dilveen, and that the serpent calls out to him every Monday morning, is firmly believed by the lower orders who live in the neighbourhood of the Lough.

St. Patrick’s Day

Hagiography, St. Patrick, St. Patrick's Day, Traditions

From Robert Chambers, The Book of Days, 1869:

LEGENDARY HISTORY OF ST. PATRICK

The principal enemies that St. Patrick found to the introduction of Christianity into Ireland, were the Druidical priests of the more ancient faith, who, as might naturally be supposed, were exceedingly adverse to any innovation. These Druids, being great magicians, would have been formidable antagonists to any one of less miraculous and saintly powers than Patrick. Their obstinate antagonism was so great, that, in spite of his benevolent disposition, he was compelled to curse their fertile lands, so that they became dreary bogs: to curse their rivers, so that they produced no fish: to curse their very kettles, so that with no amount of fire and patience could they ever be made to boil; and, as a last resort, to curse the Druids themselves, so that the earth opened and swallowed them up.

A popular legend relates that the saint and his followers found themselves, one cold morning, on a mountain, without a fire to cook their break-fast, or warm their frozen limbs. Unheeding their complaints, Patrick desired them to collect a pile of ice and snow-balls: which having been done, he breathed upon it, and it instantaneously became a pleasant fire—a fire that long after served to point a poet’s conceit in these lines:

‘Saint Patrick, as in legends told,

The morning being very cold,

In order to assuage the weather,

Collected bits of ice together;

Then gently breathed upon the pyre,

When every fragment blazed on fire.

Oh! if the saint had been so kind,

As to have left the gift behind

To such a lovelorn wretch as me,

Who daily struggles to be free:

I’d be content—content with part,

I’d only ask to thaw the heart,

The frozen heart, of Polly Roe.’

The greatest of St. Patrick’s miracles was that of driving the venomous reptiles out of Ireland, and rendering the Irish soil, for ever after, so obnoxious to the serpent race, that they instantaneously die on touching it. Colgan seriously relates that St. Patrick accomplished this feat by beating a drum, which he struck with such fervour that he knocked a hole in it, thereby endangering the success of the miracle. But an angel appearing mended the drum: and the patched instrument was long exhibited as a holy relic.

In 1831, Mr. James Cleland, an Irish gentleman, being curious to ascertain whether the climate or soil of Ireland was naturally destructive to the serpent tribe, purchased half-a-dozen of the common harmless English snake (matrix torqueta), in Covent Garden market in London. Bringing them to Ireland, he turned them out in his garden at Rathgael, in the county of Down: and in a week afterwards, one of them was killed at Milecross, about three miles distant. The persons into whose hands this strange monster fell, had not the slightest suspicion that it was a snake, but, considering it a curious kind of eel, they took it to Dr. J. L. Drummond, a celebrated Irish naturalist, who at once pronounced the animal to be a reptile and not a fish. The idea of a ‘rale living sarpint’ having been killed within a short distance of the very burial-place of St. Patrick, caused an extraordinary sensation of alarm among the country people. The most absurd rumours were freely circulated, and credited. One far-seeing clergyman preached a sermon, in which he cited this unfortunate snake as a token of the immediate commencement of the millennium: while another saw in it a type of the approach of the cholera morbus. Old prophecies were raked up, and all parties and sects, for once, united in believing that the snake fore-shadowed. ‘the beginning of the end,’ though they very widely differed as to what that end was to be. Some more practically minded persons, however, subscribed a considerable sum of money, which they offered in rewards for the destruction of any other snakes that might be found in the district. And three more of the snakes were not long afterwards killed, within a few miles of the garden where they were liberated. The remaining two snakes were never very clearly accounted for; but no doubt they also fell victims to the reward. The writer, who resided in that part of the country at the time, well remembers the wild rumours, among the more illiterate classes, on the appearance of those snakes: and the bitter feelings of angry indignation expressed by educated persons against the—very fortunately then unknown—person, who had dared to bring them to Ireland.

A more natural story than the extirpation of the serpents, has afforded material for the pencil of the painter, as well as the pen of the poet. When baptizing an Irish chieftain, the venerable saint leaned heavily on his crozier, the steel-spiked point of which he had unwittingly placed on the great toe of the converted heathen. The pious chief, in his ignorance of Christian rites, believing this to be an essential part of the ceremony, bore the pain without flinching or murmur; though the blood flowed so freely from the wound, that the Irish named the place St. fhuil (stream of blood), now pronounced Struill, the name of a well-known place near Downpatrick. And here we are reminded of a very remarkable fact in connection with geographical appellations, that the footsteps of St. Patrick can be traced, almost from his cradle to his grave, by the names of places called after him.

Thus, assuming his Scottish origin, he was born at Kilpatrick (the cell or church of Patrick), in Dumbartonshire. He resided for some time at Dalpatrick (the district or division of Patrick), in Lanarkshire; and visited Crag-phadrig (the rock of Patrick), near Inverness. He founded two churches, Kirkpatrick at Irongray, in Kireudbright; and Kirkpatrick at Fleming, in Dumfries: and ultimately sailed from Portpatrick, leaving behind him such an odour of sanctity, that among the most distinguished families of the Scottish aristocracy, Patrick has been a favourite name down to the present day.

Arriving in England, he preached in Patterdale (Patrick’s dale), in Westmoreland: and founded the church of Kirkpatrick, in Durham. Visiting Wales, he walked over Sarn-badrig (Patrick’s causeway), which, now covered by the sea, forms a dangerous shoal in Carnarvon Bay: and departing for the Continent, sailed from Llan-badrig (the church of Patrick), in the island of Anglesea. Undertaking his mission to convert the Irish, he first landed at Innis-patrick (the island of Patrick), and next at Holmpatrick, on the opposite shore of the mainland, in the county of Dublin. Sailing northwards, he touched at the Isle of Man, sometimes since, also, called. Innis-patrick, where he founded another church of Kirkpatrick, near the town of Peel. Again landing on the coast of Ireland, in the county of Down, he converted and baptized the chieftain Dichu, on his own threshing-floor. The name of the parish of Saul, derived from Sabbal-patrick (the barn of Patrick), perpetuates the event. He then proceeded to Temple-patrick, in Antrim, and from thence to a lofty mountain in Mayo, ever since called Croagh-patrick.

He founded an abbey in East Meath, called Domnach-Padraig (the house of Patrick), and built a church in Dublin on the spot where St. Patrick’s Cathedral now stands. In an island of Lough Deng, in the county of Donegal, there is St. Patrick’s Purgatory: in Leinster, St. Patrick’s Wood; at Cashel, St. Patrick’s Rock; the St. Patrick’s Wells, at which the holy man is said to have quenched his thirst, may be counted by dozens. He is commonly stated to have died at Saul on the 17th of March 493, in the one hundred and twenty-first year of his age.

Poteen, a favourite beverage in Ireland, is also said to have derived its name from St. Patrick: he, according to legend, being the first who instructed the Irish in the art of distillation. This, however, is, to say the least, doubtful: the most authentic historians representing the saint as a very strict promoter of temperance, if not exactly a teetotaller. We read that in 445 he commanded his disciples to abstain from drink in the day-time, until the bell rang for vespers in the evening. One Colman, though busily engaged in the severe labours of the field, exhausted with heat, fatigue, and intolerable thirst, obeyed so literally the injunction of his revered preceptor, that he refrained from indulging himself with one drop of water during a long sultry harvest day. But human endurance has its limits: when the vesper bell at last rang for evensong, Colman dropped down dead—a martyr to thirst. Irishmen can well appreciate such a martyrdom; and the name of Colman, to this day, is frequently cited, with the added epithet of Shadhack—the Thirsty.

‘In Burgo Duno, tumulo tumulantur in uno,

Brigida, Patricius, atque Columba pins.’

Which may be thus rendered:

‘In the hill of Down, buried in one tomb,

Were Bridget and Patricius, with Columba the pious.’

One of the strangest recollections of a strange childhood is the writer having been taken, by a servant, unknown to his parents, to see a silver case, containing, as was said, the jaw-bone of St. Patrick. The writer was very young at the time, but remembers seeing one much younger, a baby, on the same occasion, and has an indistinct idea that the jaw-bone was considered to have had a very salutary effect on the baby’s safe introduction into the world. This jaw-bone, and the silver shrine enclosing it, has been, for many years, in the possession of a family in humble life near Belfast. In the memory of persons living, it contained five teeth, but now retains only one—three having been given to members of the family, when emigrating to America; and the fourth was deposited under the altar of the Roman Catholic Chapel of Derriaghy, when rebuilt some years ago.

The curiously embossed case has a very antique appearance, and is said to be of an immense age: but it is, though certainly old, not so very old as reported, for it carries the Hallmark ‘plainly impressed upon it.’ This remarkable relic has long been used for a kind of extra-judicial trial, similar to the Saxon corsnet, a test of guilt or innocence of very great antiquity; accused or suspected persons freeing themselves from the suspicion of crime, by placing the right hand on the reliquary, and declaring their innocence, in a certain form of words, supposed to be an asseveration of the greatest solemnity, and liable to instantaneous, supernatural, and frightful punishment, if falsely spoken, even by suppressio veri, or suygestio falsi. It was also supposed to assist women in labour, relieve epileptic fits, counteract the diabolical machinations of witches and fairies, and avert the baleful influence of the evil eye. We have been informed, however, that of late years it has rarely been applied to such uses, though it is still considered a most welcome visitor to a household, where an immediate addition to the family is expected.

The shamrock, or small white clover (trifolium repens of botanists), is almost universally worn in the hat over all Ireland, on St. Patrick’s day. The popular notion is, that when St. Patrick was preaching the doctrine of the Trinity to the pagan Irish, he used this plant, bearing three leaves upon one stem, as a symbol or illustration of the great mystery. To suppose, as some absurdly hold, that he used it as an argument, would be derogatory to the saint’s high reputation for orthodoxy and good sense: but it is certainly a curious coincidence, if nothing more, that the trefoil in Arabic is called skamrakh, and was held sacred in Iran as emblematical of the Persian Triads. Pliny, too, in his Natural History, says that serpents are never seen upon trefoil, and it prevails against the stings of snakes and scorpions. This, considering St. Patrick’s connexion with snakes, is really remarkable, and we may reasonably imagine that, previous to his arrival, the Irish had ascribed mystical virtues to the trefoil or shamrock, and on hearing of the Trinity for the first time, they fancied some peculiar fitness in their already sacred plant to shadow forth the newly revealed and mysterious doctrine. And we may conclude, in the words of the poet, long may the shamrock,

‘The plant that blooms for ever,

With the rose combined,

And the thistle twined,

Defy the strength of foes to sever.

Firm be the triple league they form,

Despite all change of weather:

In sunshine, darkness, calm, or storm,

Still may they fondly grow together.’

W. P.

The serpent every Monday morning calls out in Irish, ‘It is a long Monday, Patrick.’

That St Patrick chained the serpent in Lough Dilveen, and that the serpent calls out to him every Monday morning, is firmly believed by the lower orders who live in the neighbourhood of the Lough.