Category Archive 'The Raj'

23 Sep 2017

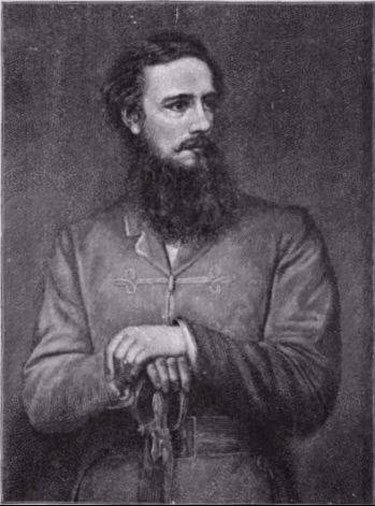

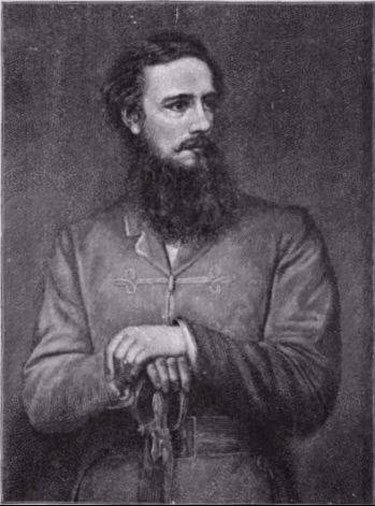

Brigadier-General John Nicholson CB (11 December 1821 – 23 September 1857)

Robert Shane Hawes reminds us:

On this day in 1857 legendary Brigadier General John Nicholson died of the wounds he received when he led the storming of Delhi during the Indian Mutiny. it took nine days for him to die as he would only allow himself to go after he knew the battle was over, that Delhi had fallen, that the Mughal Emperor had been captured, and the rebellion crushed.

He was just 34 years old.

A veteran of the First Anglo Afghan and Anglo Sikh wars, where he was renowned for his daring exploits and decorated for bravery, Nicholson was also a God fearing Ulsterman of fierce repute who kept the severed head of a convicted outlaw on his desk as a warning to criminals and who hunted Bengal tigers on horseback using only a cavalry sabre.

One famous story recounted by Charles Allen in Soldier Sahibs is of a night during the rebellion when Nicholson strode into the British mess tent at Jullunder, coughed to attract the attention of the officers, then said, “I am sorry, gentlemen, to have kept you waiting for your dinner, but I have been hanging your cooks.” He had been told that the regimental chefs had poisoned the soup with aconite. When they refused to taste it for him, he force fed it to a monkey and when it dropped dead on the spot, he proceeded to hang the cooks from a nearby tree without a trial!

Nicholson also called for the Mutiny to be punished with greater severity. He proposed an Act endorsing a ‘new kind of death for the murderers and dishonourers of our women’, suggesting, ‘flaying alive, impalement or burning,’ and commenting further, ‘I would inflict the most excruciating tortures I could think of on them with a perfectly easy conscience.’

A tablet in the church at Bannu in present day Pakistan where Nicholson served as Deputy Commissioner from 1852-1854 carries the following inscription: “Gifted in mind and body, he was as brilliant in government as in arms. The snows of Ghazni attest his youthful fortitude; the songs of the Punjab his manly deeds; the peace of this frontier his strong rule. The enemies of his country know how terrible he was in battle, and we his friends have to recall how gentle, generous, and true he was.”

Interestingly, he was also worshipped as a god in some parts of rural Punjab until the 1980’s, while sadly most people in our own country have never even heard of him.

One of the four Houses of the Royal School Dungannon is named after him and it is the youngest House at the school. There is also a statue of him in the city centre of Lisburn, Northern Ireland. His grave is in Delhi, India.

Badass of the week article

Nikal Seyn left a long memory in the Punjab. link:

Charles Allen reports that when in Bannu in 1999 he found the following expression of irritation common – “Te zan ta Nikal Seyn wayat?”- “Who do you think you are – Nicholson?”

16 May 2013

Tiger Again Coming To The Charge

The actual story referred to in the title of Lieut.-Colonel Frank Sheffield’s How I Killed the Tiger (1902) amounts to only 36-pages (including numerous, highly evocative, illustrations), but even the second edition is not easy to find and will cost you something in the neighborhood of $100.

But we happily live in the age of marvels, in which even such esoteric treasures are already scanned in and sitting there available in electronic form at the touch of a fingertip.

Col. Sheffield’s yarn is quite a story.

I would not myself want to take on a fully grown Bengal Tiger with an unreliable percussion fowling piece, even if I had a couple of General John Jacob’s explosive bullets in my pocket. But, if I had been so foolhardy as to do so and wound up once knocked down and mauled by a tiger, I’d like to hope that –like Col. Shefield–, faced with another charge, I’d still have “some kick in me” and stand there, Bowie knife in hand, “determined to make a hard fight for it.”

“How I Killed the Tiger” text

“How I Killed the Tiger” plates

Hat tip to Karen L. Myers.

30 Mar 2009

From Col. C.E. Callwell, C.B.’s Service Yarns and Memories, William Blackwood, 1912:

Ever since a distinguished Crimean veteran one day came down to the Royal Military Academy to hear reports of Examiners and of the Governor and of other people solemnly read out, and I found myself transformed into a commissioned officer, the Service, according to the verdict of unimÂpeachable authorities, has been going to the dogs —one had not heard of it as a cadet. But even the most determined pessimists allow that occaÂsional bright patches display themselves in the overcast and stormy sky; and an example of such a patch is found in the fact that newly-caught subalterns who know nothing whatever, no longer have drafts flung at their heads to take out to the uttermost parts of the earth, as they did in those days. My very first experience of responsibility after appearing in the ‘Army List’ was the taking over of some forty gunners and drivers at Woolwich, and conducting them to Allahabad where somebody else luckily assumed control over them.

It was about 8 A.M. on a wintry January mornÂing that I encountered the draft for the first time on the imposing parade-ground in front of the Artillery Barracks. It was drawn up alongside another, somewhat larger, draft, which was under charge of a subaltern of a few months’ standÂing. A crowd of officers of various grades were standing about, the R.A. Band was all ready to speed us on our way, and strong bodies of gunÂners, who apparently were not proceeding to the East because they had no bags and other things at their feet, formed a phalanx in rear. I had joined the previous day, and had then been enÂtrusted with big packets of documents connected with my party, and the major commanding the depôt had at the same time made reference to “credits” and “money due to the men” and “toÂmorrow morning,” which conveyed no meaning to my mind. “Ah, there you are. That’s right,” said the major, bustling up to me with a nonÂcommissioned officer in tow, who was cherishing a haversack; “I’ll hand you over the money now, and the list of credits.”

The non-commissioned officer produced a porÂtentous sheet of paper, with a column of names on it and various sums noted down against each name. “Where are you going to put it?” deÂmanded the major. One was arrayed in a tunic in those days when in marching order, and anything like a haversack would have been grossly irregular. Where was the document to go? “Try your sabretache,” suggested somebody, and various people assisted me in exploring that outÂrageous article of personal impedimenta, and in cramming the list of credits into its penetralia.” Well done! Now for the money, and then you’ll be fitted out all complete,” said the major enÂcouragingly; whereupon the non-commissioned officer produced two handfuls of gold and silver and copper coins out of the haversack. “Haven’t you anywhere to put it?” The dross was even worse than the document. I had never seen so much money before at one time in my life, and had no idea how much it amounted to, having neglected to investigate the list which was now stuffed away safely in the sabretache.

“There’s always a pocket in overalls, up at the top,” suggested a bystander. But to get at that pocket would have involved taking off a sword-belt, to say nothing of embarking upon other and even more precarious processes.

“Surely you’ve got a pocket in the breast of your tunic; I have in mine,” remarked another friend in need. Now it is no light thing to unbutton the breast of a new tunic when there is a cross-belt in the way, when one’s hands are encased in thick, stiff pipe-clayed gloves, and when one’s fingers are numbed with the cold. The operation was nevertheless successfully accomÂplished, and, true enough, the caricature of a pocket disclosed itself in the lining of the garment (where the padding is inserted to give one a chest), one of the sort which will hold next to nothing, which will not retain what is put into them, and which are so contrived that you never know whether what you try to put into them has got in or not. The pocket was a miracle of inconvenience, and by this time my bosom was all over pipe-clay like a 17th Lancer’s, but just then the Assistant-Quartermaster-General shouldered his way into the group. “I say! Time’s getting on,” he interrupted; “what’s all this delay about?”

” Come, get the money into your pocket,” urged the depôt major impatiently.

“Weel ye tak’ off yer-r gloves, ma mannie. Dinna fash yer-rself,” put in a kindly surgeon-major, who was there to see that none of the travellers contracted some fell disease at the last moment.

“D’you mean to say that you aren’t going to see if it’s all right ?” exclaimed the Assistant-Quartermaster-General, absolutely aghast.

But I had wits enough left not to start upon counting goodness only knows how much money, standing out there shivering on the parade-ground, so I shovelled the coins into my bosom, and had the satisfaction of feeling that a good percentage of them had found their way into the pocket. There was an unmistakable lump in one place. On making investigations with the assistÂance of the other subaltern after getting into the train, it transpired that there was a shortage of two or three sovereigns as compared with the list of credits; but after arriving on board H.M.S. Serapis, and carrying investigations further, nearly the whole of the deficient monies turned up in my boots. You may abuse the combination of overalls and Wellingtons as much as you like. You may inveigh against the arrangement as uncomfortable and unserviceable, and all the rest of it. But the system does have this one advantage. If something carries away high up— a collar-stud, say, or a pin—the thing is not gone beyond recall: it turns up at the end of the day in one of your boots.

“Now then! Hurry up and get into your place, will you,” ordered the depôt major in a fuss. ” You don’t want to inspect them, I suppose; anyway there is no time for it now.” I did not want to inspect them in the very least. Even to an inexperienced eye they presented an un-martial and unprepossessing appearance, and I obediently took up my station in their vicinity. ” March off, please,” directed the Assistant-QuarÂtermaster-General. “‘Tion! Fours right! Quick march.'” bawled the other subaltern, who being-senior was of course in command of the parade. The drafts somehow transformed themselves out of an irregular line into a still more irregular swarm; the RA. Band thundered “The Girl He Left Behind Him,” and away we streamed—one cannot call it marched—down the hill to the Arsenal Station.

The object of the phalanx of gunners and others who had been drawn up in rear of the drafts now made itself apparent. By a deft manoeuvre they disposed themselves along the flanks and the rear of the troops bound for Asia, while a select party of good-conduct-badge-bedecked veterans assumed the role of wreckers in rear-guard, charged with the picking up of stray men who had collapsed, and of kit-bags which had been abandoned in the stress of the progress. The drafts were composed almost entirely of old soldiers, who were in that condition which may be said to include every stage of exhilaration from the paralytic to that commonly described in the orderly-room as “havÂing had beer.” However, we got to the station somehow, and there the confusion seemed, to one unaccustomed to such scenes, to almost border on a riot. But although in a disorderly mood, the drafts were merely light-hearted, and in any case they were hopelessly outnumbered, they were bundled into compartments by willing hands, as each compartment filled, stalwart gunners forced the door to, and the guard instantly locked it. Almost before one realised the workÂings of an efficient organisation the task was completed and the whistle sounded. The crowd of officers who had assisted in the engagement, a look of relief depicted on their faces, waved their hands to us cheerily in our first-class compartÂment, the band broke out into “Auld Lang Syne,” the drafts responded with a hurricane of inarticÂulate noises, and we were fairly off on our way to Hindustan.

30 Jan 2009

Lt. Gen. H.G. Martin, in his memoir of soldiering and sport in pre-War British India, Sunset From the Main (1951), recalls an unpleasant encounter on angling expedition to the Simla Hills in search of mahseer.

The steep path dropped down to the bed of the gorge past brakes of thorn and matted evergreen and across unexpected lawns where the encircling cactus reared its knotted candleabras, rigid and grotesque as submarine coral-beds. In these occasional clearings troops of brown monkeys basked, scratching in the sunshine: plebeian monkeys, vulgar, thieving, shameless, who lowered and gibbered as we passed. I do not love the brown monkey. Who has ever seen him look pleasant? A typical, politically minded proletarian, he has the Communist’s capacity for hating all creation.

/div>

Feeds

|