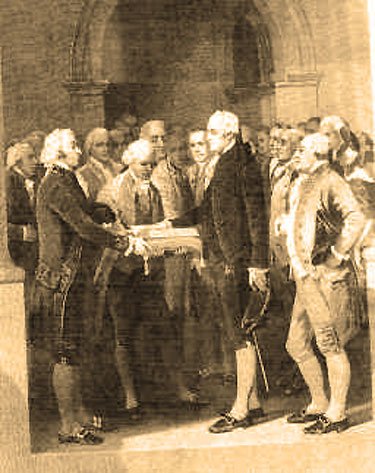

Chancellor Livingston administers the Oath of Office to Washington.

Stephen L. Carter is intelligent enough to recognize that County Clerk Kim Davis’s stand cannot simply be dismissed by saying that “she ought to do her job.” Kim Davis is, in fact, doing her job when she disobeys Justice Roberts.

I’m reluctant to disagree with my Bloomberg View colleague Noah Feldman, but after a bit of reflection and research, I’ve concluded that he got things slightly wrong in his recent column about Kim Davis. Davis, the Kentucky county clerk who was held in contempt for defying a federal judge’s order to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples, has argued that her religious freedom is being violated. What caught Feldman’s attention was her claim that her oath of office, which ends with “so help me God,†entitles her to invoke a higher law when necessary. Feldman thinks she’s mistaken. I wish she were; I fear she’s not. …

[When the 18th century theologian William] Paley takes up the subject of the oath of allegiance to the monarch — an oath also taken in the name of God, and a closer approximation to an oath of office. That oath, Paley argues, does not apply when the king’s own misbehavior “makes resistance beneficial to the community†or when the commands of the sovereign “are unauthorized by law.â€

For Paley, as for many others of the day, the oath of allegiance was never a promise to obey all laws. It was a promise to obey the just ones. …

This is the sense of oath-taking that Davis is invoking: that in the case of a conflict between God’s law and man’s, the oath itself requires her obedience to the higher.

Davis’s argument for relying on her oath of office as justification for disregarding the law of the land is well grounded in history.

It’s also dangerous.