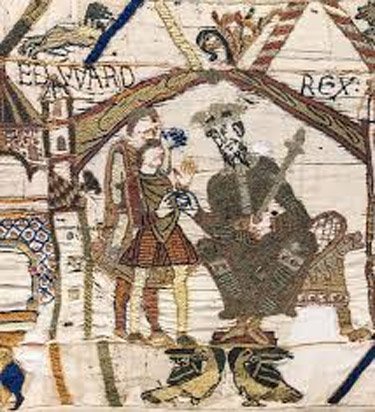

Edward the Confessor depicted in the Bayeaux Tapestry.

Historical novelist Paula Lofting describes Christmas time in England just before the Norman Conquest.

Winter began in November, according to Anglo-Saxon tradition. The 7th of November to be exact, and from the 15th of November, 40 days before the Christmas season began, it was a time of fasting and alms giving, which was the origin for gift-giving at Christmas. ‘Christmas’, comes from the Anglo-Saxon, Cristesmæsse, a word first recorded in 1038. It replaced the old pagan ‘yule-tide’, known back then as Geola and still referred to when talking about yule logs etc. As we know, the early Christian church instructed their emissaries to allow the Christianisation of some pagan traditions, a clever strategy on their part, to encourage people to give up their pagan ways by allowing them to retain some of the features and customs of the old religion. During this time of fasting and strict observance, it was not just the clergy who were expected to fast, attend prayers and vigils, and give alms to the more unfortunates of their world, but the secular communities also. It was a sign of your wealth and status if you could afford to give alms, something that many people were eager to do, for the Anglo-Saxons were as keen as any for their soul to get a free pass to the afterlife.

So, that was a lot of days of hardship for less than half the days in return of feasting! Anyway, that aside, only those who were employed to do necessary tasks, were excused from taking 12 days off work. Quite honestly, I could not imagine anyone complaining about that unless they were one of those who were engaged in those aforesaid important occupations.

Oh, there’s one other little thing I have forgotten, there were no carnal relations allowed during this fasting period, after all, with all the vigils and extra prayers and psalm singing, how was one going to fit in having sex as well? But, should one fail in this expectation, and need absolution to restore their spiritual equilibrium with God, there was always confession and more fasting as penance.

During King Edward’s time, the Christmas period was usually spent at Gloucester. Edward was a keen sporting huntsman, something the church frowned on but were able to forgive because he was pious in other aspects of his life. Since the Forest of Dean was his favourite hunting ground, it seemed natural that after a good Autumn’s hunting, that he would spend Christmas at King’s Holme in Gloucester. He did, however, spend his last Christmas on this earth in the newly built palace of Westminster, whilst the new church of St Peter was consecrated that year, in time for the celebrations and his funeral. …

It couldn’t have been much fun that year of 1065, when he succumbed at last to the illness that seemed to have been brought on by the exile of his favourite courtier, Earl Tostig. The stress of losing Tostig and having to give in to the recalcitrant northerners a few months earlier, obviously affected him badly, because hitherto, he had been quite robust and sprightly for an old man of sixty; a great age in those times. So, Christmas of 1065 would have been quite a miserable one that year, so perhaps we should hearken back to happier times, and the Christmas of ’64, when having had a good hunting session during the month of October and some of November, Edward was ready to put on his virtuous head, start the fasting and alms giving and settle down to pottage for supper each night until the 25th December when the holiday would begin.

Kings Holme (now known as Kingsholm) was the site of an old Roman fortress, significant in size to have made the Roman city an important strategic place. We know that there was definitely a palace located there in 1051, and possibly, it may have dated back much further. At least by 1064, the palace was a well-used one, having been one of three important palaces in Edward’s England, besides Westminster, in London, and Winchester. A hoard of early 11thc coins was found at the site and said to be a large collection from probably a wide area, indicating that this was not and just any old burh. To add to the evidence of its possible magnificence, excavations at the site have uncovered indications of large timber buildings dating to around this time.

We cannot say what King Edward’s palace consisted of for sure, but there must have been quite a few domestic and guest quarters amongst the buildings found. At Christmas time, the whole of Edward’s court would have been present in Gloucester, and among them, his secular officials as well as many foremost ecclesiasticals, bishops and abbots and possibly some Abbesses, some of whom were very powerful indeed. Many of the king’s thegns would have been there, and possibly they brought their wives with them, perhaps some brought their sons also, and maybe their daughters, to be presented at court. If those who owed service to the king couldn’t make it for whatever reason, then they would no doubt have to send a representative. The most important of the king’s guests, would have been the archbishops, Ealdred of York and Stigand of Canterbury, and leading earl of the realm, Harold Godwinson. Aside from them, the other lords of the earldoms: Tostig of Northumbria, Morcar of Mercia, Oswulf of Bamburgh, Leofwin and Gyrth Godwinson, earls of the South Eastern Counties and East Anglia respectively, and Waltheof, son of the great Siward, Tostig’s predecessor. No doubt they would also have brought their wives and perhaps their families too, not to mention their retinues, servants, and household guards. No wonder there were several large buildings found on the complex, they would have needed them to house everyone.

Its most likely that Edward’s great feasting hall was a timber construction, as no evidence for stone foundations have been found during the excavation. Edward had been building his wonderful complex at Westminster in stone, but that was a special undertaking that had been under construction for years. The king’s feasting-hall was basically a large-scale version of the smaller halls that one might find on manorial estates. It was rectangular, with doors in the longest sides, front and back, and possibly with ante chambers at both ends, perhaps one of those rooms could have been where the king and queen slept. The space inside would have been large enough to contain a good few hundred people and was the heart of the community during the Christmas period. During the last few days of fasting before the feast of Christ, the final touches to the décor would have been carried out. Around the walls, were murals decorating the lime washed walls and possibly hung with fine embroidered hangings depicting biblical scenes. Holly and Ivy would have decked the hall, a throw-back to earlier times. Things might have changed somewhat from the early days of the mead-halls as described by Steven Pollington in his book The Mead-Hall, where a lot of the symbel (the feasting) had its rituals rooted in Pagan beliefs and old Teutonic ideals based on the ways of warriors. However, the principle that the hall was the place where the joys of life could be found, drink, merriment, and good times, remained even in the 11thc. The feasting-hall, or the mead-hall, was where it all happened, much like how some of us nowadays see pubs, clubs, restaurants, and bars.

Please Leave a Comment!