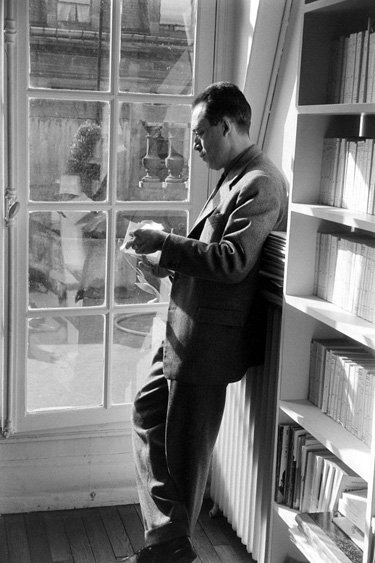

“[Camus’] death in 1960 was felt as a personal loss by the whole literate world.” — Susan Sontag

Did the KGB arrange the death of Nobel Prize winning writer Albert Camus in a car accident in 1960?

An article which appeared in the Italian paper Corriere della Sera on August 1 quotes Eastern European scholar Giovanni Catelli, who discovered that the complete version of the Diary of Czech poet and translator Jan Zábrana contained a reference to the death of Albert Camus omitted from abridged French and Italian translations.

The Diary account (translated from the Corriere della Sera article by JDZ)

From a man who knows many things and is in contact with informed sources, I heard something very strange. He said the accident in which Camus died in 1960 was arranged by Soviet intelligence. They produced a blow-out, using a technical device which cut or punctured the car’s tire at high speed. The order for the action was given personally by the [Soviet Foreign] Minister [Dmitri] Shepilov, as “payback” for the article published in “Franc-tireur” in March 1957, in which Camus, in connection with events in Hungary, had attacked the minister explicitly by name.

Jan Zábrana’s contact with “informed sources” was speculated by Corriere to have been either of two relatively litle-known academics: George Gibian or Jiri Zuzanek.

—————————–

The Accident (translated from the Corriere della Sera article by JDZ)

On the morning of January 4, 1960, a cold and foggy Monday, the asphalt around the village of Thoissey in central France was covered with frost. The car, being driven by Michel Gallimard (Camus’s publisher), had left the day before from the Riviera and was now four hours from Paris. In the car, besides Camus, seated in the rear were Janine, wife of the publisher, and Anne, his daughter. The previous evening, the party had celebrated Anne’s 18th birthday with toasts and good wishes at the inn Chapon Fin. They left after breakfast, between nine and ten in the morning, proceeding calmly, at moderate speed, on a straight road, nine meters wide, with almost no traffic and good visibility. They were joking about the writer’s latest romance and trying to guess the identity of the person waiting for him in Paris. Just before Petit-Villeblevin, Janine Gallimard suddenly heard her husband cry: Merde! And then the vehicle’s steering suddenly unaccountably went out of control, followed by a shock strong enough to make it seem as if “something had collapsed under the car.” Experts say that probably the seizure of wheel bearing or the rupture of a tire caused Gallimard to lose control, sending him crashing into one of the plane trees that lined the road. Camus was extracted from the wreckage already dying, his skull fractured and his neck broken.

—————————–

There are chronological problems with all this.

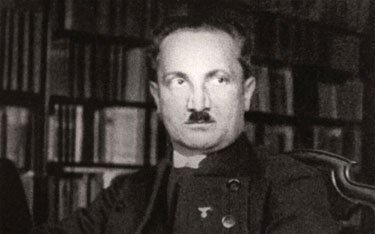

Dmitri Shepilov was replaced as Soviet Foreign Minister 15 February 1957 by Andrei Gromyko. The article identified as offending Shepilov appeared in March. Shepilov, however, moved from the Foreign Ministry to the post of Secretary of the Central Committee, which he held until 29 June 1957 when he was removed and demoted for being part of a group which attempted to oust Nikita Krushchev from power.

It is not impossible to imagine that a Secretary of the Central Committee would be no less able than a Foreign Minister to order a KGB hit, but Shepilov was out of favor completely and in the process of descending to the level of an ordinary clerk in the State archives when Camus died in 1960.

Still, Albert Camus was an extremely prominent and widely respected and admired intellectual figure, whose prestige was particularly potent in international left-wing intellectual circles. His criticism of the Soviet invasion of Hungary and of subsequent brutalities and oppression was unquestionably particularly damaging to the Soviet Union’s prestige and reputation.

Camus subsequently offended the Soviet Union significantly again, when he championed Boris Pasternak’s novel Dr. Zhivago at the time of its publication in the West. Pasternak’s book, which rapidly acquired a major readership and became an established classic, described the violence and inhumanity of the Revolution and the Russian Civil War and its publication in Russia had been banned by Stalin.

It is certainly not beyond the realm of possibility, nor would the murder of Albert Camus have been out of character for the KGB. The Russian intelligence service has always been renowned for the assassination of prominent opponents of the Soviet regime, and has demonstrated a particular penchant for using ingenious devices.

The Bulgarian writer Georgi Markov, for instance, was assassinated using an umbrella capable of pneumatically firing a tiny projectile embedded with ricin in the victim’s body.

If the little-known Markov was worth killing in 1978, when the Cold War was simmering quietly at a low ebb late in the game, one must reflect just how much more valuable a target Camus would have been, and how much more bloodthirsty the Soviets would have been in 1960, just a few years after the revolt in Hungary, when the Soviet Union was winning the Space Race, Castro had just seized power in Cuba, and Krushchev was promising “We will bury you!”

The Czech diary account is just a thinly-sourced story, and is completely unproven, but it could be true.

Guardian article

Daily Star (Lebanon) article

Hat tip to John Brewer.

Galliamard’s wrecked Facel Vega FV3B