Category Archive 'Archaeology'

15 May 2020

Very cool news from the History blog:

In October 2018, a geophysical survey of a field in Halden, southeastern Norway, revealed the presence of Viking ship burial. The landowner had applied for a soil drainage permit and because the field is adjacent to the monumental Jell Mound, archaeologists from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) inspected the site first. Using a four-wheeler with a georadar mounted to the front of it. The high-resolution ground-penetrating radar picked up the clear outline of a ship 20 meters (65 feet) long.

The ship was found just 50 cm (1.6 feet) under the surface. It was once covered by a burial mound like its neighbor, but centuries of agricultural work ploughed it away. Subsequent investigation of the area found the outlines of at least 11 other burial mounds around the ship, all of them long-since ploughed out as well. The georadar also discovered the remains of five longhouses.

In order to get some idea of the ship’s age, condition and how much of it is left, in September of 2019, NIKU archaeologists dug a test pit was dug to obtain a sample of the wood of the keel. The keel was of a different type to ones from other Viking ship burials known in Norway. It is thinner and smaller than usual. The two-week investigation and analysis of the sample found that the ship does indeed date to the early Viking era. The wood was felled between the late 7th century and the start of the 9th century. Later dendrochronological analysis narrowed down the date to the period between 603 and 724 A.D.

In more distressing news, the analysis of the sample revealed that the wooden remains were under severe attack from fungus. The use of fertilizer on the farmland above the ship encourages the fungal growth and not only is the keel plagued by soft rot, the remains even at the deepest point where preservation conditions are the best possible are under acute distress.

Norway’s government has responded to the archaeological emergency by allocating 15.6m kroner (about $1.5 million) to excavate the Gjellestad Viking Ship and get it out of the ground before it rots to nothingness. While other Viking ship burials have been excavated in recent years, the last Viking ship burial mound to be excavated was the Oseberg ship in 1904-1905. If the Norwegian parliament approves the budget, excavation of the Gjellestad Ship is slated to begin in June.

RTWT

HT: Bird Dog.

31 Mar 2020

Archaeology World:

Orichalcum, the lost metal of Atlantis, may have been found on a shipwreck off Sicily

A group of naval archeologists has uncovered two hundred ingots spread over the sandy seafloor near a 2,600-year-old shipwreck off the coast of Sicily. The ingots were made from orichalcum, a rare cast metal that ancient Greek philosopher Plato wrote was from the legendary city of Atlantis.

A total of 39 ingots (metal set into rectangular blocks) were, according to Inquisitr, discovered near a shipwreck. BBC reported that another same metal cache was found. 47 more ingots were found, with a total of 86 metal pieces found to date.

The wreck was discovered in 1988, floating about 300 meters (1,000 ft) off the coast of Gela in Sicily in shallow waters. At the time of the shipwreck Gela was a rich city and had many factories that produced fine objects. Scientists believe that the pieces of orichalcum were destined for those laboratories when the ship sank.

Sebastiano Tusa, Sicily’s superintendent of the Sea Office, told Discovery News that the precious ingots were probably being brought to Sicily from Greece or Asia Minor.

Tusa said that the discovery of orichalcum ingots, long considered a mysterious metal, is significant as “nothing similar has ever been found.†He added, “We knew orichalcum from ancient texts and a few ornamental objects.â€

According to a Daily Telegraph report, the ingots have been analyzed and found to be made of about 75-80 percent copper, 14-20 percent zinc and a scattering of nickel, lead, and iron.

The name orichalucum derives from the Greek word oreikhalkos, meaning literally “mountain copper†or “copper mountainâ€. According to Plato’s 5th century BC Critias dialogue, orichalucum was considered second only to gold in value, and was found and mined in many parts of the legendary Atlantis in ancient times

Plato wrote that the three outer walls of the Temple to Poseidon and Cleito on Atlantis were clad respectively with brass, tin, and the third, which encompassed the whole citadel, “flashed with the red light of orichalcumâ€.

The interior walls, pillars, and floors of the temple were completely covered in orichalcum, and the roof was variegated with gold, silver, and orichalcum. In the center of the temple stood a pillar of orichalcum, on which the laws of Poseidon and records of the first son princes of Poseidon were inscribed.

For centuries, experts have hotly debated the metal’s composition and origin.

According to the ancient Greeks, orichalcum was invented by Cadmus, a Greek-Phoenician mythological character. Cadmus was the founder and first king of Thebes, the acropolis of which was originally named Cadmeia in his honor.

Orichalcum has variously been held to be a gold-copper alloy, a copper-tin, or copper-zinc brass, or a metal no longer known. However, in Vergil’s Aeneid, it was mentioned that the breastplate of Turnus was “stiff with gold and white orachalc†and it has been theorized that it is an alloy of gold and silver, though it is not known for certain what orichalcum was.

RTWT

HT: Karen L. Myers.

02 Mar 2020

Seymour Tower: the researchers get to live there.

Atlas Obscura:

When the water laps up on the granite rocks and sandy embankments off the coast of Jersey, the largest of the Channel Islands, ancient artifacts get wet. It isn’t a disaster. It’s been happening for thousands of years, in fact, in a daily rhythm—the water rushing in rivulets that turn into torrents along the beachy landscape, sweeping across the miles of exposed seabed and rising above it.

This May, alongside the gulls and crustaceans that skitter about, archaeologists will scamper away from the rising sea as their fieldwork is submerged. They’ll retreat.

With its pockmarked and inundated topography, the intertidal reef known as the Violet Bank is awash with history. Yet despite its name, the bank is a changing gradient of blues, grays, greens, and browns—a cryptic mix of rocky earth and transient sea. Now a preferred spot for low-water fishing—or pêche à pied‚ where locals chat in Jèrriais and probe the ebb tide for shellfish—the evanescent landscape remains treacherous, catching unsuspecting visitors with its rapid tidal shifts.

When an archaeological team from University College London visits the deceptive, disappearing bank in May, they’ll hardly be unsuspecting. They’ll know the tidal drill well, as they try to learn more about the origins of lithic (stone) artifacts and mammoth remains that have emerged from the crevices and ravines that are revealed by the surf with each tide.

RTWT

06 Feb 2020

Science Alert:

The old well doesn’t look like much – a wooden crate-like object, dilapidated, crumbling a little. But according to new research, it’s really special. A tree-ring dating technique has revealed that the oak wood used to make it was cut around 7,275 years ago.

This makes it the oldest known wooden structure in the world that’s been confirmed using this method, scientists say.

“According to our findings, based particularly on dendrochronological data, we can say that the tree trunks for the wood used were felled in the years 5255 and 5256 BCE,” explained archaeologist Jaroslav PeÅ¡ka of the Archaeological Centre Olomouc in the Czech Republic in a press statement last year.

“The rings on the trunks enable us to give a precise estimate, give [or] take one year, as to when the trees were felled.”

The well was unearthed and discovered near the town of Ostrov in 2018 during construction on the D35 motorway in the Czech Republic. Ceramic fragments found inside the well dated the site to the early Neolithic, but no evidence of any settlement structures were found nearby, suggesting the well serviced several settlements at a bit of a distance away.

It was filled with dirt, so an archaeological team carefully excavated and extracted it. It consisted of four oak poles, one at each corner, with flat planks between them. The well was roughly square, measuring 80 by 80 centimetres (2.62 feet). It stood 140 centimetres tall (4.6 feet), with a shaft that extended below ground level and into the groundwater.

Even in waterlogged conditions, the state of preservation of the wood was exceptional, showing marks from the polished stone tools used to shape each piece.

“The construction of this well is unique,” PeÅ¡ka said.

“It bears marks of construction techniques used in the Bronze and Iron ages and even the Roman Age. We had no idea that the first farmers, who only had tools made of stone, bones, horns, or wood, were able to process the surface of felled trunks with such precision.”

And that amazing state of preservation also allowed for dendrochronological (based on tree rings) and radiocarbon dating, based on radioactive isotopes of carbon.

According to these techniques, the trees that supplied wood to the flat planks on the sides of the well were felled around 7,275 years ago. That’s probably when the well was constructed. But two of the poles told a different story.

Both were felled earlier – one around 7,278 or 7,279 years ago; and the other around nine years before that. This, the researchers concluded, meant that the two posts must have been used previously, and repurposed into posts for the well.

One of the side planks also had a different age. It was quite a bit younger, felled between 7,261 and 7,244 years ago. This is likely because of a repair to the well at some point.

RTWT

18 Dec 2019

Wired reports the results of an interesting study of ancient human DNA.

Nearly 6,000 years ago, in a seaside marshland in what is now southern Denmark, a woman with blue eyes and dark hair and skin popped a piece of chewing gum in her mouth. Not spearmint gum, mind you, but a decidedly less palatable chunk of black-brown pitch, boiled down from the bark of the birch tree. An indispensable tool in her time, birch pitch would solidify as it cooled, so the woman and her comrades would have had to chew it before using it as a sort of superglue for, say, making tools. Our ancient subject may have even chewed it for its antiseptic properties, perhaps to ease the pain of an infected tooth.

Eventually she spit out the gum, and six millennia later, scientists found it and ran the blob through a battery of genetic tests. They not only found the chewer’s full genome and determined her sex and likely skin and hair and eye color, they also revealed her oral microbiome—the bacteria and viruses that pack the human mouth—as well as finding the DNA of hazelnut and duck she may have recently consumed. All told, from a chunk of birch pitch less than an inch long, the researchers have painted a remarkably detailed portrait of the biology and behavior of an ancient human.

When that birch pitch hit the ground 5,700 years ago, the European continent was playing host to a full-tilt transformation of its human residents. Agriculture was spreading north from the Middle East, and humans were literally and figuratively planting roots—if you’re looking after crops, you’re staying put and building up infrastructure to support your efforts, not following around herds of wild game.

But several converging lines of evidence indicate that this gum-chewing woman actually was a hunter-gatherer, thousands of years after the invention of agriculture. For one, previous analyses have allowed scientists to associate certain genes with either agricultural or hunter-gatherer lifestyles. They did this by matching DNA samples with archaeological evidence for those people—farming tools versus hunting tools, for instance.

The genetics of this ancient woman point to the hunter-gatherer way of life, matched with contemporaneous archeological evidence from the area. “You find lots of fish traps and eel-catching prongs and spears,†says University of Copenhagen geneticist Hannes Schroeder, coauthor on a new paper in Nature Communications describing the findings. Evidence of a more settled lifestyle at the site only came later in history.

RTWT

02 Dec 2019

Vilnius, Lithuania’s 2019 Christmas Tree.

Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, has been making a point of trying to erect the most beautiful Christmas Tree in Europe in recent years. (link)

November 30, 2019: The traditional lighting of the Christmas tree in Vilnius attracted citizens and guests alike. The capital of Lithuania has received a lot of global attention over the years for its unique and stunning Christmas trees, and this year is no exception. This year, the decorated Christmas tree resembles the 14-15th century Queen figure from the game of chess, which was found by archaeologists in 2007.

Decorations adorn the already traditional 27-meter tall metal construction, which bears some 6,000 branches. The construction is specially designed to create a completely sustainable Christmas tree. All the actual tree branches used in the construction are defiled from the trees by foresters while carrying out the general maintenance of the forest. Therefore not only trees but even branches are not cut just for the spectacle.

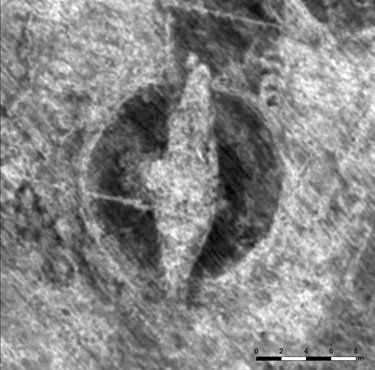

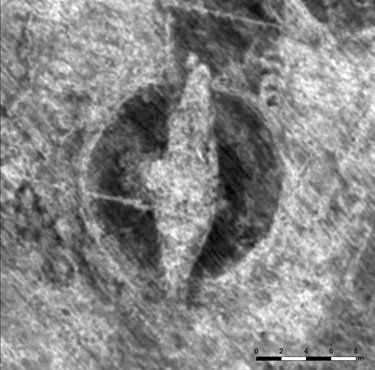

The particular figure which served as a model for decorations was found during the archaeological excavations around the Ducal Palace in Vilnius. Dating back to the 14th-15th century, the beautifully ornamented figure was made of spindle tree. Its middle part is carved with geometrical patterns and topped with floral ornaments. According to historians, the game of chess was played by the nobility of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from the end of the 14th century.

A traditional Christmas market is set up around the Christmas tree, along with another one located at the Town Hall Square. The markets will stay open from the 30th of November to the 7th of January.

—————————-

The tree’s design was inspired by this 14th-15th Chess Queen found by archaeologists in 2007.

22 Nov 2019

One of two “Emperor” coins.

Too bad that the metal detectors got greedy and fell afoul of the authorities. The Guardian has pictures and the story.

On a sunny day in June 2015 amateur metal detectorists George Powell and Layton Davies were hunting for treasure in fields at a remote spot in Herefordshire.

The pair had done their research carefully and were focusing on a promising area just north of Leominster, close to high land and a wood with intriguing regal names – Kings Hall Hill and Kings Hall Covert.

But in their wildest dreams they could not have imagined what they were about to find when the alarm on one of their detectors sounded and they began to dig.

Powell and Davies unearthed a hoard hidden more than 1,000 years ago, almost certainly by a Viking warrior who was part of an army that retreated into the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia after being defeated by Alfred the Great in 878.

There was gold jewellery including a chunky ring, an arm bracelet in the shape of a serpent and a small crystal ball held by thin strips of gold that would have been worn as a pendant. Beneath the gold were silver ingots and an estimated 300 silver coins.

The law is clear: such finds should be reported to the local coroner within 14 days and failure to do so risks an unlimited fine and up to three months in prison. Any reward may be split between the finder, land owner and land occupier.

Powell and Davies, experienced detectorists from south Wales, chose a different route. Two days later they went to a Cardiff antiques centre called the Pumping Station and showed some examples of their find to coin dealer Paul Wells. He immediately knew they were very special.

The crystal ball pendant turned out to be the oldest item, probably dating from the 5th or 6th century, while the ring and arm bracelet are thought to be 9th- century. They were described as priceless in court. Nothing like the arm bracelet has ever been seen by modern man before.

But if anything, the coins turned out to be even more significant. Among them were extremely rare “two emperor†coins depicting two Anglo-Saxon rulers: King Alfred of Wessex and Ceolwulf II of Mercia. They are important because they give a fresh glimpse of how Mercia and Wessex were ruled in the 9th century at about the time England was morphing into a single united kingdom.

Still, the pair did not contact the authorities. Instead Powell got in touch with another treasure hunter, Simon Wicks from East Sussex, and two weeks after the find he presented himself at upmarket coin auctioneers Dix Noonan Webb in Mayfair, central London.

Wicks put a selection of the coins found in Herefordshire, including a pair of the two emperors, in front of one its leading experts. The expert gasped when he saw the coins and suggested the two emperors could be worth £100,000 each.

Meanwhile, whispers that Powell and Davies had struck gold had begun to circulate and on 6 July – 33 days after their discovery – the Herefordshire finds liaison officer, Peter Reavill, contacted Powell and Davies and gently asked if they had anything to tell him about.

Powell initially replied with a firm denial but they eventually handed over the gold jewellery and an ingot. However, they insisted they had only found a couple of damaged coins that they did not need to declare.

But the net was closing in. Police visited Wells’ house and he showed them five coins from the hoard that had been stitched into his magnifying glass case. When he was arrested he said: “I knew it would come to this.â€

RTWT

The rock crystal pendant.

03 Nov 2019

British scientists have reconstructed the face of a female Viking warrior who suffered a head wound and was buried with weapons.

Daily Mail:

Scientists have re-created the face of a female Viking warrior who lived more than 1,000 years ago.

The woman is based on a skeleton found in a Viking graveyard in Solør, Norway, and is now preserved in Oslo’s Museum of Cultural History.

While the remains had already been identified as female, the burial site had not been considered that of a warrior ‘simply because the occupant was a woman’, archaelogist Ella Al-Shamahi told The Guardian.

But now British scientists have brought the female warrior to life using cutting-edge facial recognition technology.

Scientists reconstructed the face of the female warrior who lived more than 1,000 years ago by anatomically working from the muscles and layering of the skin

And scientists found the woman was buried with a hoard of deadly weaponry including arrows, a sword, a spear and an axe.

Researchers also discovered a dent in her head, which rested on a shield in her grave, that was consistent with a sword wound.

It is unclear whether the brutal injury was the cause of her death however it is believed to be ‘the first evidence ever found of a Viking woman with a battle injury’, according to Ms Al-Shamahi.

She added: I’m so excited because this is a face that hasn’t been seen in 1,000 years… She’s suddenly become really real.’

RTWT

14 Oct 2019

Peterson Type H, Wheeler Type II Viking Sword 9th Century.

Archaeology.org:

[P]ieces of some 100 Viking swords and spearheads dating to the middle of the tenth century A.D. were found in two caches placed about 260 feet apart along a remote Viking trade route near Estonia’s northwestern coast. Archaeologist Mauri Kiudsoo of Tallinn University said the bits of broken weapons may have been cenotaphs, or items left as a monument to warriors who had died and were buried somewhere else. The surviving sword parts provide enough information, however, to know the weapons included H-shaped double-edged swords. Eight nearly intact type H swords and fragments of 100 more have been found in Estonia alone.

—————————-

ERR News:

The fragments were found in two closely located sites in a coastal area of north Estonia, in the territory of the ancient Estonian county of Ravala, late last autumn.

The finds consisted of dozens of items, mostly fragments of swords and a few spearheads.

Mauri Kiudsoo, archaeologist and keeper of the archaeological research collection of Tallinn University, told BNS the two sites were located just 80 meters apart. The swords date from the middle of the 10th century and are probably cenotaphs, grave markers dedicated to people buried elsewhere.

The reason why the swords were not found intact, Kiudsoo said, is due to the burial customs of the time. It is characteristic of finds in Estonia from the period that weapons were put into the graves broken or rendered unusable.

While the Ravala fragments constitute the biggest find of Viking-era weapons in Estonia, more important according to Kiudsoo, is the fact that the grips of the swords allow us to determine which type of swords they are. They have been identified as H-shaped double-edged swords. This type of sword was the most common type in the Viking era and over 700 have been found in northern Europe.

Kiudsoo said that by 1991, eight more or less intact type H swords and about 20 fragments had been discovered in Estonia but the number has risen to about 100. The overwhelming majority of the Estonian finds have come to light on the country’s north coast, which lies by the most important remote trade route of the Viking era.

Sword Pommel, XI-XIII century from Läänemaa, Estonia.

10 May 2019

The Guardian reports on new information on findings from the Essex grave of a 6th Century Anglo-Saxon prince.

Archaeologists on Thursday will reveal the results of years of research into the burial site of a rich, powerful Anglo-Saxon man found at Prittlewell in Southend-on-Sea, Essex.

When it was first discovered in 2003, jaws dropped at how intact the chamber was. But it is only now, after years of painstaking investigation by more than 40 specialists, that a fuller picture of the extraordinary nature of the find is emerging.

Sophie Jackson, director of research at Museum of London Archaeology (Mola), said it could be seen as a British equivalent to Tutankhamun’s tomb, although different in a number of ways.

For one thing it is in free-draining soil, meaning everything organic has decayed. “It was essentially a sandpit with stains,†she said. But what a sandpit. “It was one of the most significant archaeological discoveries we’ve made in this country in the last 50 to 60 years.â€

The research reveals previously concealed objects, paints a picture of how the chamber was constructed and offers new evidence of how Anglo-Saxon Essex was at the forefront of culture, religion and exchange with other countries across the North Sea.

It also throws up a possible name for the powerful Anglo-Saxon figure for whom the grave was built.

Previously, the favourite suggestion was a king of the East Saxons, Saebert, son of Sledd. But he died about 616 and scientific dating now suggests the burial was in the late-6th century, about 580.

That means it could be Saebert’s younger brother Seaxa although, since the body has dissolved and only tiny fragments of his tooth enamel remain, it is impossible to know for certain.

Gold foil crosses were found in the grave which indicate he was a Christian, a fact which has also surprised historians.

Sue Hirst, Mola’s Anglo-Saxon burial expert, said that date was remarkably early for the adoption of Christianity in England, coming before Augustine’s mission to convert the country from paganism.

But it could be explained because Seaxa’s mother Ricula was sister to king Ethelbert of Kent who was married to a Frankish Christian princess called Bertha. “Ricula would have brought close knowledge of Christianity from her sister-in-law.â€

Recreating the design of the burial chamber has been difficult because the original timbers decayed leaving only stains and impressions of the structure in the soil.

But it has been possible. The Mola team estimates it would have taken 20 to 25 men working five or six days in different groups to build the chamber and would have involved felling 13 oak trees.

“It was a significant communal effort,†said Jackson. “You’ve got to see this burial chamber as a piece of theatre. It is sending out a very strong message to the people who come and look at it and the stories they take away from it. It says ‘we are very important people and we are burying one of our most important people’.â€

Objects identified in the grave include a wooden lyre – the ancient world’s most important stringed instrument – which had almost entirely decayed apart from fragments of wood and metal fittings preserved in a soil stain.

Micro-excavation in the lab has revealed it was made from maple, with ash tuning pegs, and had garnets in two of the lyre fittings which are almandines, most likely from the Indian subcontinent or Sri Lanka. It had also been broken in two at some point and put back together.

The burial chamber was discovered only because of a proposal to widen the adjacent road. It was fully excavated and the research has been undertaken by experts in a range of subjects including Anglo-Saxon art, ancient woodworking, soil science and engineering.

The new Mola findings are published on Thursday ahead of a long-awaited new permanent display of Prittlewell princely burial objects at Southend Central Museum. It opens on Saturday and will include objects such as a gold belt buckle, a Byzantine flagon, coloured glass vessels, an ornate drinking horn and a decorative hanging bowl. People will also be able to explore the burial chamber online at www.prittlewellprincelyburial.org.

Essex has sometimes been seen as something of an Anglo-Saxon backwater but the Prittlewell burial chamber suggests otherwise.

“What it really tells us,†said Hirst, “is that the people in Essex, in the kingdom of the East Saxons at this time, are really at the forefront of the political and religious changes that are going on.â€

National Geographic article

16 Dec 2018

The Human Remains of Skeleton Lake – Visible Only when the Ice Melts.

From Quora, a pretty interesting story.

In 1942, H K. Madhawl, a British forest guard in Roopkund, India made an alarming discovery (despite the fact that there had been reports of bones on the lake shore since the mid 19th century). At an elevation of 15,750 feet, near the bottom of a small valley, was a frozen lake absolutely full of skeletons. Roopkund Lake, in the state of Uttarakhand, India, was a six-foot-deep glacial lake that typically remained frozen year round.

What he saw up there confused everyone. At first, it was one bone. But as the temperatures rose, the number of exposed remains grew exponentially. That summer, the ice melting revealed even more skeletal remains, floating in the water and lying haphazardly around the lake’s edges. People wondered what happened, and what were these people doing up here?

The immediate assumption (it being war time) was that these were the remains of Japanese soldiers who had died of exposure while sneaking through India. The British government, terrified of a Japanese land invasion, sent a team of investigators to determine if this was true. However upon examination they realized these bones were not from Japanese soldiers—they weren’t new enough.

With the immediate concerns of war eased, the urgency of identifying the remains became less of a priority and efforts to further analyze the remains were sidelined. It was evident that the bones were quite old indeed. Flesh, hair, and the bones themselves had been preserved by the dry, cold air, but no one could properly determine exactly when they were from. More than that, they had no idea what had killed over 300 people in this small valley. Many theories were put forth including an epidemic, landslide, and ritual suicide. For decades, no one was able to shed light on the mystery of Skeleton Lake.

But what caused their death? Was there a massive landslide? Did some disease strike suddenly? Were the individuals conducting a ritualistic suicide? Did they die of starvation? Were they killed in an enemy attack? One theory even suggests that the individuals did not die at the scene of the lake, but their bodies were deposited there as a result of glacial movement.

A 2004 expedition to the site seems to have finally revealed the mystery of what caused those people’s deaths. The answer was stranger than anyone had guessed.

The 2004 expedition took samples of the bones as well as bits of preserved human tissues. As it turns out, all the bodies date to around 850 AD.

DNA evidence indicates that there were two distinct groups of people, one a family or tribe of closely related individuals, and a second smaller, shorter group of locals, likely hired as porters and guides. A number of these victims of the mountain were so well preserved that they still had remnants of flesh, hair, fingernails, and clothes. Rings, spears, leather shoes, and bamboo staves were found, leading experts to believe that the group was comprised of pilgrims heading through the valley with the help of the locals.

The plausible scenario of what exactly happened? The two groups perhaps met at the foot of the mountain. The first of the two, taller and who which outnumbered the others, probably wanted to make a pilgrimage pass through the mountain and are thought to have been of Iranian origin. The second group, with thinner and smaller bones, showed up as their local Indian guides. The travelers were related to each other (a large family or tribe), and could have come from Iran. The locals that guided the way were unrelated.

Another suggestion is that they braved the elements to collect “Keeda Jadi,†which are larvae of the ghost moth that have become the home to a fungus (that actually wraps around the larvae and slowly devours it).

These “Magical Mushrooms†are believed to have incredible medicinal properties and locals head out in search of them in the springtime.

The journey should have progressed well until the point everyone was trapped, with no place to run and hide as a disaster struck. A violent torrent of baseball-sized hailstones falling from the skies battered the whole group. All the bodies had died in a similar way, from blows to the head. However, the short deep cracks in the skulls appeared to be the result not of weapons, but rather of something rounded. The bodies also only had wounds on their heads, and shoulders as if the blows had all come from directly above. What had killed them all, porter and pilgrim alike?

Among Himalayan women there is an ancient and traditional folk song. The lyrics state that “these are the holy lands of the Goddess Nanda, her sanctuary in the mountains. King Jasdal of Kanauj and his wife were undertaking the “Nanda Jat†pilgrimage; along the way, the queen gave birth. Instead of pleasing their goddess with their tributes, the deity was angered for this defielment of her pure mountain. To punish the group, she sent a great snowstorm, flinging iron-like hailstones that took the life of each and every personâ€.

After much research and consideration, the 2004 expedition came to the same conclusion. All 300 people died from a sudden and severe hailstorm. Trapped in the valley with nowhere to hide or seek shelter, the “hard as iron†cricket ball-sized [about 23 centimeter/9 inches circumference] hailstones came by the thousands, resulting in the travelers’ bizarre sudden death. The remains lay in the lake for 1,200 years until their discovery.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Archaeology' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|