Category Archive 'Art'

23 May 2019

Joachim Friess, Diana and Stag automata drinking cup, 1620, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

href=”https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/193623″>Elizabeth Cleland, 2017:

This object was prized, though not unique; other versions survive, all targeted at the wealthiest clientele. A wind-up mechanism once moved the group forward on hidden wheels, making it vibrate as if with life. Uniting modern technology, precious casework, and visual appeal, automatons were celebrated as a novelty entertainment for guests of the most moneyed classes. Removing the stag’s head reveals a drinking vessel; the diner in front of whom the piece stopped had to drain the cup.

HT: Karen L. Myers.

28 Apr 2019

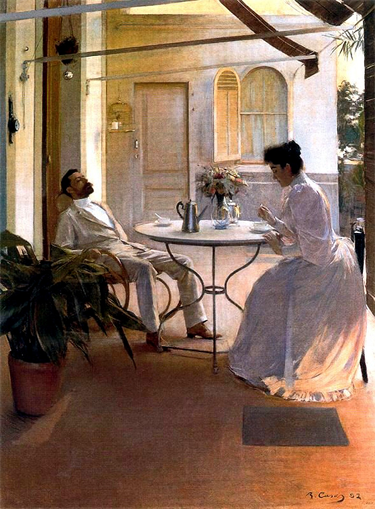

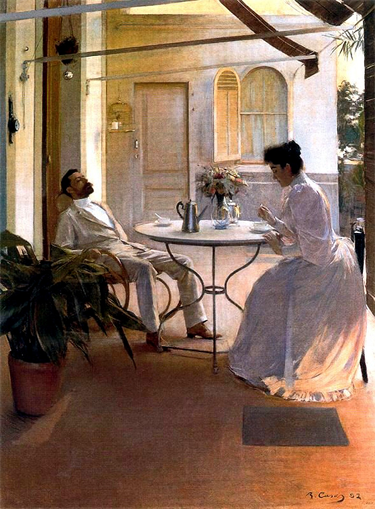

Ramon Casas i Carbó, “Interior al aire libre (Outdoor interior), 1892, La Colección Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.

02 Apr 2019

Andrew Dickson, in the Guardian, describes the complexities of loaning, packing, shipping, uncrating, and displaying important works of art.

Even if you are an obsessive gallery-goer, it’s possible you haven’t put much thought into how the works on the wall came to be there. The art world prefers it this way: what happens behind the signs reading “No Entry: Installation in Progress†remains a ferociously guarded secret. The only hint that this Song dynasty bronze has arrived from that private collection in Taiwan, for example, is a discreet credit on the wall. It may be that, absorbed in our face-to-face encounter with the artwork – what Walter Benjamin described as its “aura†– many of us prefer not to gaze too deeply into that mystery.

Yet the mechanisms required to get that bronze from Taipei to St Ives – loan agreements, insurance, packing, couriering, shipping, handling, installation – are delicate, expensive and complex. Behind every exhibition is an intricate logistical web that reaches across the globe.

Institutions are under huge pressure to share collections, both in the UK and internationally. Missed Frida Kahlo at the V&A? It has recently opened at Brooklyn Museum, just as the Metropolitan Museum’s 2017 exhibition of early Diane Arbus has come to London. The British Museum’s A History of the World in 100 Objects is shortly to arrive in Hong Kong, by way of Abu Dhabi, Taiwan, Japan, Australia and China. It has been on the road since 2016. Many museums now rely on blockbuster exhibitions to drive visitor numbers; often, the only way of paying for these is to partner with another institution and send the show on tour.

The demands of creating large shows populated with star loans, and the logistics required to make them come together, are intense. “It has become a sort of arms race,†said one curator I spoke to, with a trace of a sigh.

A hyperactive art market creates a momentum all its own. According to the most recent analysis, global art sales total nearly $68bn (£52bn) annually, a 10% increase since 2008, with some 40m transactions made last year alone. Vast quantities of art are continually being shifted from auction houses to purchasers to dealers and back again, especially in the fast-expanding Asian markets. Two decades ago, there were around 55 major commercial art fairs; now, there are more than 260.

The end result is that more art than ever, worth more money than ever, is travelling more than ever. Fine-art shipping is expensive, specialised and technically challenging work. Old masters are fragile, but some contemporary sculptures are so friable – or so poorly fabricated – that moving them anywhere is a major risk. And there is the added pressure of handling artefacts that are almost immeasurably culturally important.

There is perhaps another paradox here, too: desperate for a glimpse of genuine “aura†in an era of digital reproduction, we crave that once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see those real Cézannes sharing a real wall, and stand in their presence, as the artist stood. But although the real value of a work of art lies in its being seen, simply putting it on display – let alone making it travel – is guaranteed to put it at risk, and probably shorten its life. “At the end of the day, you have to make your peace with that,†one conservator said. “You have to think what art is for.â€

RTWT

25 Feb 2019

Frederic Leighton, 1st Baron Leighton, Flaming June, 1895, Museo de Arte de Ponce, Ponce, Puerto Rico.

My Modern Met:

The color orange has a long history that dates back centuries. The ancient Egyptians used a yellow-orange hue made from the mineral realgar in their tomb paintings. As with many minerals used to make pigments, realgar is highly toxic—it contains arsenic—and was used by the Chinese to repel snakes, in addition to being used in Chinese medicine.

Another related mineral, orpiment, was also used to make pigments. Just as toxic as realgar, it was also a highly prized trade item in Ancient Rome. Orpiment leans toward a golden yellow-orange and its resulting pigment, as well as that of realgar, was used in Medieval times in illuminated manuscripts.

Interestingly, in Europe, the color orange didn’t have a name until the 16th century. Prior to that time it was simply called yellow-red. Before the word orange came into common use in English, saffron was sometimes used to describe the deep yellow-orange color. This changed when orange trees were brought to Europe from Asia by Portuguese merchants. The color was then named after the ripe fruit, which carries through many different languages. Orange in English, naranja in Spanish, arancia in Italian, and laranja in Portuguese.

RTWT

A good color for starting conversations when worn on St. Patrick’s Day.

20 Feb 2019

At Christie’s February 27th Sale:

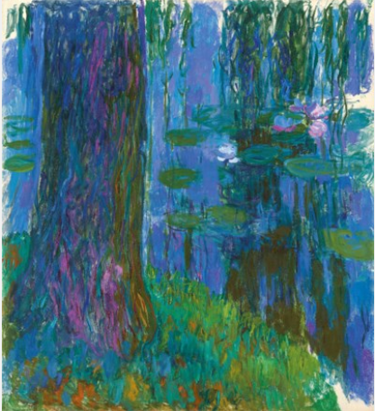

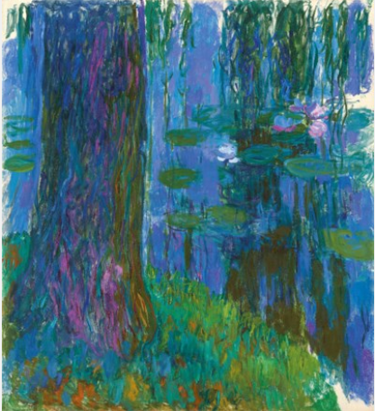

Lot 11

— Claude Monet (1840-1926)

Saule pleureur et bassin aux nymphéas [Weeping willow and pond with water lilies]

stamped with signature ‘Claude Monet’ (Lugt 1819b; lower left)

oil on canvas

78 1/2 x 70 3/4 in. (199 x 180 cm.)

Painted in Giverny in 1916-1919.

Estimate “upon request,” meaning: If you have to ask, you can’t afford it.

29 Jan 2019

In Paris, renovation work for a new retail store wound up revealing a treasure concealed within the wall. NYT

Alex Bolen, the chief executive of Oscar de la Renta, planned to have his new store in Paris open around this week, just in time for the couture shows. He planned to have a presence in the city even if he didn’t have a show. He had it all figured out.

Then, last summer, in the middle of renovations, Mr. Bolen got a call from his architect, Nathalie Ryan.

“‘We made a discovery,’†he remembered her saying. On the other end of the phone, Mr. Bolen cringed. The last time he received a call like that about a store, their plans to move a wall had to be scrapped because of fears the building would collapse. He asked what, exactly, the discovery was.

“You have to come and see,†she told him.

So, gritting his teeth, he got on a plane from New York. Ms. Ryan took him to the second floor of what would be the shop, where workers were busily clearing out detritus, and gestured toward the end of the space. Mr. Bolen, she said, blinked. Then he said: “No, it’s not possible.â€

Something had been hidden behind a wall, and it wasn’t asbestos. It was a 10-by-20-foot oil painting of an elaborately coifed and dressed 17th-century marquis and assorted courtiers entering the city of Jerusalem.

“It’s very rare and exceptional, for many reasons,†said Benoît Janson, of the restoration specialists Nouvelle Tendance, who is overseeing work on the canvas. Namely, “its historical and aesthetic quality and size.†…

Demolition was halted to figure out what the painting was and how it came to be in what was about to be a shop. Seeing the aristocrats on horseback and the mosque in the picture, Mr. Bolen said, visions of Crusaders and Knights Templar began to dance in his head. “I think maybe I have seen too many movies,†he said. …

So when the painting was found, and it became clear Mr. Bolen would have to talk to the building’s owners, whom he had never met (the lease had been negotiated through a broker), his relative was able to make the introductions. Another de La Rochefoucauld, who happened to work at the Louvre, got a recommendation for an art historian: Stephane Pinta of the Cabinet Turquin, an expert in old-master paintings.

Mr. Pinta determined that the painting was an oil on canvas created in 1674 by Arnould de Vuez, a painter who worked with Charles Le Brun, the first painter to Louis XIV and designer of interiors of the Château de Versailles. After working with Le Brun, de Vuez, who was known for getting involved in duels of honor, was forced to flee France and ended up in Constantinople.

Mr. Pinta traced the painting to a plate that was reproduced in the 1900 book “Odyssey of an Ambassador: The Travels of the Marquis de Nointel, 1670-1680†by Albert Vandal, which told the story of the travels of Charles-Marie-François Olier, Marquis de Nointel et d’Angervilliers, Louis XIV’s ambassador to the Ottoman Court. On Page 129, there is a rotogravure of an artwork depicting the Marquis de Nointel arriving in Jerusalem with great pomp and circumstance — the painting on the wall.

But how it ended up glued to that wall, no one knew, nor why it was covered up. There was speculation that maybe it happened during World War II, given the setting. It could be “a fog-of-war issue,†Mr. Bolen said.

RTWT

23 Jan 2019

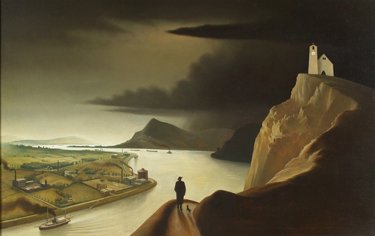

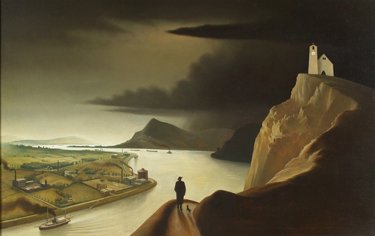

Franz Sedlacek, Industrielandschaft.

Franz Sedlacek (1891–1945) was an Austrian painter who belonged to the tradition known as “New Objectivity” (“neue Sachlichkeit”), an artistic movement similar to Magical Realism. He served as an officer in the German Army during the Second World War, fighting at Stalingrad and in Norway. He disappeared somewhere in Poland in January of 1945.

19 Nov 2018

Japan. Edo period.

1 1/2” – 3.8cm

A miniature Furuyaishi rock, the grey stone of the mountain riven by a wide white torrent and a narrow waterfall. With a hardwood stand and a box inscribed ‘Waterfall Rock’.

Brandt Asian Art

04 Nov 2018

Rembrandt, Old Man Leaning on a Stick, 1632-1635, Robert Lehman Collection, Metropolitan Museum.

/div>

Feeds

|