Category Archive 'Class Warfare'

08 Jan 2012

Charles Murray, in the New Criterion, discusses the threat of American upper middle class arrogance and provincialism to American exceptionalism.

As recently as half a century ago, Americans across all classes showed only minor differences on the Founding virtues. When Americans resisted the idea of being thought part of an upper class or lower class, they were responding to a reality: there really was such a thing as a civic culture that embraced all of them. Today, that is no longer true. Americans have formed a new lower class and a new upper class that have no precedent in our history. American exceptionalism is deteriorating in tandem with this development. …

The members of America’s new upper class tend not to watch the same movies and television shows that the rest of America watches, don’t go to kinds of restaurants the rest of America frequents, tend to buy different kinds of automobiles, and have passions for being green, maintaining the proper degree of body fat, and supporting gay marriage that most Americans don’t share. Their child-raising practices are distinctive, and they typically take care to enroll their children in schools dominated by the offspring of the upper middle class—or, better yet, of the new upper class. They take their vacations in different kinds of places than other Americans go and are often indifferent to the professional sports that are so popular among other Americans. Few have served in the military, and few of their children either.

Worst of all, a growing proportion of the people who run the institutions of our country have never known any other culture. They are the children of upper-middle-class parents, have always lived in upper-middle-class neighborhoods and gone to upper-middle-class schools. Many have never worked at a job that caused a body part to hurt at the end of the day, never had a conversation with an evangelical Christian, never seen a factory floor, never had a friend who didn’t have a college degree, never hunted or fished. They are likely to know that Garrison Keillor’s monologue on Prairie Home Companion is the source of the phrase “all of the children are above average,†but they have never walked on a prairie and never known someone well whose IQ actually was below average.

When people are making decisions that affect the lives of many other people, the cultural isolation that has grown up around America’s new upper class can be disastrous. It is not a problem if truck drivers cannot empathize with the priorities of Yale law professors. It is a problem if Yale law professors, or producers of the nightly news, or CEOs of great corporations, or the President’s advisors, cannot empathize with the priorities of truck drivers. …

Tocqueville, when explaining why the American system ensured that a despot could never successfully divide Americans against each other, wrote that “local freedom . . . perpetually brings men together, and forces them to help one another, in spite of the propensities which sever them. In the United States, the more opulent citizens take great care not to stand aloof from the people. On the contrary, they constantly keep on easy terms with the lower classes: they listen to them, they speak to them every day.†That’s not true any more. Our propensities do sever us, and the new upper class shows no inclination to reach out across the widening divide. And so the unraveling of the civic culture in Fishtown occurs without the knowledge or the concern of Belmont, let alone with any attempt by Belmont to assist the people of Fishtown who are still trying to do the right thing. Fishtown is flyover country, or those ugly suburbs that the people of the new upper class view from afar as they drive from their enclave in Greenwich to their office in midtown Manhattan.

21 Dec 2011

Professor Stephen G. Bloom: “I’ve lived in many places, lots of them foreign countries, but none has been more foreign to me than Iowa.”

Stephen G. Bloom, a professor at the University of Iowa, in the Atlantic, describes with wonder and deep contempt the bizarre and backward culture of the state in which he disapprovingly resides.

Whether a schizophrenic, economically-depressed, and some say, culturally-challenged state like Iowa should host the first grassroots referendum to determine who will be the next president isn’t at issue. It’s been this way since 1972, and there are no signs that it’s going to change. In a perfect world, no way would Iowa ever be considered representative of America, or even a small part of it. Iowa’s not representative of much. There are few minorities, no sizable cities, and the state’s about to lose one of its five seats in the U.S. House because its population is shifting; any growth is negligible. Still, thanks to a host of nonsensical political precedents, whoever wins the Iowa Caucuses in January will very likely have a 50 percent chance of being elected president 11 months later. Go figure.

Maybe Ambrose Bierce described it right when he called the U.S. president “the greased pig in the field game of American politics.” For better or worse, Iowa’s the place where that greased pig gets generally gets grabbed first. …

Iowa is a throwback to yesteryear and, at the same time, a cautionary tale of what lies around the corner.

Which brings up my dog. And here’s why: My dog is a kind of crucible of Iowa.

What does Hannah, a 13-year-old Labrador, have to do with an analysis of the American electoral system and how screwy it is that a place like Iowa gets to choose — before anyone else — the person who may become the next leader of the free world?

For our son’s eighth birthday, we wanted to get him a dog. Every boy needs a dog, my wife and I agreed, and off we went to an Iowa breeding farm to pick out an eight-week-old puppy that, when we knelt to pet her, wouldn’t stop licking us. We chose a yellow Lab because they like kids, have pleasant dispositions, and I was particularly fond of her caramel-color coat. Labs don’t generally bite people, although they do like to chew on shoes, hats, and sofa legs. Hannah was Marley before Marley.

Our son, of course, got tired of Hannah after a couple of months, and to whom did the daily obligation of walking the dog fall?

That’s right. To me.

And here’s the point: I can’t tell you how often over the years I’d be walking Hannah in our neighborhood and someone in a pickup would pull over and shout some variation of the following:

“Bet she hunts well.”

“Do much hunting with the bitch?”

“Where you hunt her?”

To me, it summed up Iowa. You’d never get a dog because you might just want to walk with the dog or to throw a ball for her to fetch. No, that’s not a reason to own a dog in Iowa. You get a dog to track and bag animals that you want to stuff, mount, or eat.

That’s the place that may very well determine the next U.S. president.

Read the whole thing.

Hat tip to Tim Grosseclose.

—————————-

A mild rejoinder from the Des Moines Register.

—————————

Iowahawk responds with “Is This Hell? No, It’s Iowa.”

14 Dec 2011

Via Theo.

29 Nov 2011

Moe Lane marvels that, after so long a time, the Democrat Party’s New Deal coalition, consisting of “unions, city machines, blue-collar workers, farmers, blacks, people on relief, and generally non-affluent progressive intellectuals,” is being pronounced dead by the New York Times. The new coalition of the American left is simply writing off the white working class, period.

Whether you agreed with the New Deal program or not, you could always actually define it in terms that were internally self-consistent. Broadly speaking, it was a broad agreement among various groups that America’s most pressing problems could be managed and ameliorated on a broad scale through ‘expert’ and judicious government intervention; and that such intervention dampened the uncertainty and anxiety that might otherwise cause societal panics and economic dislocations. Again: you don’t have to agree with that (I don’t) to recognize that it existed as a coherent policy.

But now that has gone by the wayside, to be replaced with a system that . . . apparently plans to trade support for permanent government dependency programs for minorities, in exchange for legislating the fringe progressive morality of affluent urbanites. Aside from the utter lack of an unifying intellectual or moral framework to such an arrangement, it’s unclear exactly who benefits less from it; while it’s certainly not in minority voters’ long, medium, or short-term interests to become a permanent underclass, it’s not exactly clear that minority voters are even particularly ready to vote for a progressive social policy (as an examination of recent reversals in same-sex marriage movement in California and Maryland will readily attest). But then, that is not really the goal, is it? The goal is to re-elect President Obama — which is something that poor African-American and rich liberal voters both wish to do — and if that is accomplished, then anything else is extra. Which is just as well, because nobody really expects Obama to have much in the way of coat-tails this go-round.

Jim Geraughty, in his Morning Jolt email, responds:

Ah, but look, today’s Democratic party isn’t really about addressing economic opportunity or even dealing with America’s most pressing problems. For starters, many Democrats are not persuaded in the slightest that the annual deficit, accumulating debt, and ticking time bomb of entitlements are pressing problems at all. If Democrats really expected electing Obama would solve problems, they would be angrier with him than we are. No, for most Democrats, their political party is about a cultural identity. That identity is heavily based on not being one of those people — i.e., Republicans or conservatives. As far as I can tell, there are three inviolate principles in the modern Democratic Party:

Any form of consensual sexual behavior is to be accepted — if not celebrated. With that central belief comes the policies of abortion on demand for any woman at any age free, free contraceptives in schools, and gay marriage, and the insistence that Bill Clinton’s lying under oath about Monica Lewinsky didn’t matter because it was about sex. Complaining about explicit sexual content in pop culture reaching an audience that isn’t ready for it — e.g., Tipper Gore in the 1980s — is the sign of the square and the prude. As no less an expert political philosopher than Meghan McCain told us, “the GOP doesn’t understand sex” and has “an unhealthy attitude about sex and desire.” (Republicans are supposedly repressed and sexless, even though they generally have more children.)

America is a deeply racist country, even though you have to look far and wide to find anyone who openly expresses the belief that one race is superior to another. Everybody recoils when Imus says something snide and obnoxious about the Rutgers womens’ basketball team. Racism is never found in the central tenet of affirmative action, that minorities must be judged by a lower standard, or in the until-recently all-white lineup of MSNBC, or in the claims that Clarence Thomas and Herman Cain are Uncle Toms, or in the career of Robert Byrd. The fundamental belief of the Democratic party is that racism remains a serious problem in America today, and that the problem is found entirely in the GOP.

Credentials are to be respected, and any scoffing or skepticism at, say, the Ivy League is a sign of anti-intellectualism, ignorance, jealousy, and insecurity. Those who go there are indeed the best and the brightest; undergraduate and graduate degrees from those schools are key indicators of one’s intelligence, good judgment, and overall character. The success of dropouts Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and Mark Zuckerberg are strange anomalies, and no serious reevaluation of the higher-education system is needed. As Rush Limbaugh observed, Bill Clinton said he wanted a cabinet that “looked like America” and declared he had achieved it after assembling a group that consisted almost entirely of Ivy League-educated lawyers.

Everything else is negotiable. For a while, it appeared that Democrats were organizing themselves around the principle that almost every dispute with every other nation and group can be resolved through “tough, smart diplomacy.” But now President Obama has started killing foreigners left and right, and not too many Democrats complain at all. Obama even used a drone to kill an American citizen, Anwar al-Alwaki, with nary a peep. Don’t get me wrong, Alwaki had it coming, but this is precisely the sort of don’t-bother-me-with-legal-details-I’m-fighting-a-war philosophy that Democrats spent seven years denouncing.

You think the Democratic party cares about wealth? Come on. In their minds, George Soros spending his money to help out his political views is noble, but the Koch Brothers are evil incarnate. Higher taxes are good, but no one will complain if Tim Geithner or Charlie Rangel cut corners on paying them. One might be tempted to argue that the righteousness of unions represent an inviolate principle to Democrats, but in New York, Democratic governor Andrew Cuomo is trimming here and there and living to tell the tale.

No, the party really is about identity politics now — us vs. them. And everybody knows which side they’re on.

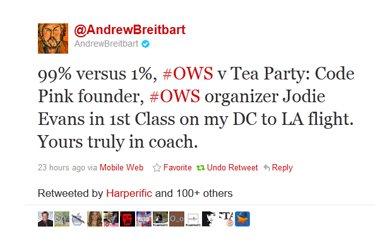

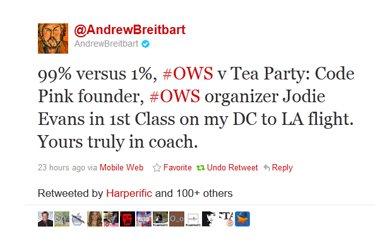

15 Nov 2011

Hat tip to Karen L. Myers.

01 Nov 2011

Kenneth Anderson penetrates through the general confusion about what the Occupy Wall Street protests are all about and explains that what we see is the indignation of the low-end intellectual clerisy left behind by more successful representatives of the same class.

The problem the New Class faces at this point is the psychological and social self-perceptions of a status group that is alienated (as we marxists say) from traditional labor by its semi-privileged upbringing — and by the fact that it is actually, two distinct strands, a privileged one and a semi-privileged one. It is, for the moment, insistent not just on white-collar work as its birthright and unable to conceive of much else. It does not celebrate the dignity of labor; it conceived of itself as existing to regulate labor. So it has purified itself to the point that not just any white-collar work will do. It has to be, as Michelle Obama instructed people in what now has to be seen as another era, virtuous non-profit or government work. Those attitudes are changing, but only slowly; the university pipelines are still full of people who cannot imagine themselves in any other kind of work, unless it means working for Apple or Google. …

The lower tier is in a different situation and always has been. It is characterized by status-income disequilibrium, to borrow from David Brooks; it cultivates the sensibilities of the upper tier New Class, but does not have the ability to globalize its rent extraction. The helping professions, the professions of therapeutic authoritarianism (the social workers as well as the public safety workers), the virtuecrats, the regulatory class, etc., have a problem — they mostly service and manage individuals, the client-consumers of the welfare state. Their rents are not leveraged very much, certainly not globally, and are limited to what amounts to an hourly wage. The method of ramping up wages, however, is through public employee unions and their own special ability to access the public-private divide. But, as everyone understands, that model no longer works, because it has overreached and overleveraged, to the point that even the system’s most sympathetic politicians understand that it cannot pay up.

The upper tier is still doing pretty well. But the lower tier of the New Class — the machine by which universities trained young people to become minor regulators and then delivered them into white collar positions on the basis of credentials in history, political science, literature, ethnic and women’s studies — with or without the benefit of law school — has broken down. The supply is uninterrupted, but the demand has dried up. The agony of the students getting dumped at the far end of the supply chain is in large part the OWS. …

The OWS protestors are a revolt — a shrill, cri-de-coeur wail at the betrayal of class solidarity — of the lower tier New Class against the upper tier New Class. It was, after all, the upper tier New Class, the private-public finance consortium, that created the student loan business and inflated the bubble in which these lower tier would-be professionals borrowed the money. It’s a securitization machine, not so very different from the subprime mortgage machine. The asset bubble pops, but the upper tier New Class, having insulated itself and, as with subprime, having taken its cut upfront and passed the risk along, is still doing pretty well. It’s not populism versus the bankers so much as internecine warfare between two tiers of elites.

This one is a must read.

Anderson is perfectly correct. Just as in places like Egypt and Tunisia, the penchant for empire-building on the part of the Academic industry combined with the general recognition of university education as the path to success and security led the United States to run through a vastly over-inflated system of ersatz higher education a large population with resulting delusions of self importance and entitlement and no means of satisfying them. Naturally, they think the system is unjust. Those other guys, over there, they have money and power, and we, the purer, nobler spirits, who majored in Afro-American Musical Traditions or Gender Inequity Studies are working in Starbucks. It’s so not fair! Rage against the Machine!

Hat tip to Megan McArdle.

30 Oct 2011

Anne Applebaum contends that the really important class division in the United States isn’t between the infinitesimally small category of the Super Rich and everybody else, but the ever enlarging fissure between the haute bourgeoisie and the ordinary middle class.

I would argue that the growing divisions within the American middle class are far more important than the gap between the very richest and everybody else. They are important because to be “middle classâ€, in America, has such positive connotations, and because most Americans think they belong in it. The middle class is the “heartlandâ€, the middle class is the “backbone of the countryâ€. In 1970, Time magazine described middle America as people who “sing the national anthem at football games – and mean itâ€.

“Middle America†also once implied the existence of a broad group of people who had similar values and a similar lifestyle. If you had a small suburban home, a car, a child at a state university, an annual holiday on a Michigan lake, you were part of it. But, at some point in the past 20 years, a family living at that level lost the sense that it was doing “wellâ€, and probably struggled even to stay there. Now it seems you need a McMansion, children at private universities, two cars, a ski trip in the winter and a summer vacation in Europe in order to feel as if you are doing minimally “wellâ€. You also need a decent retirement fund, since what the state pays is so risible, as well as an employer who can give you a generous health-care plan, since health care is so expensive.

Anne Applebaum focuses her brief discussion on the economic gap between the community of fashion elite and the old-fashioned middle classes, but I think that the cultural and political division is even more important.

The American Upper Middle Class constitutes the constituency of Progressivism, Scientism, Statism, Collectivism. They are the people who consider eating at the newest restaurant vitally important, but who never attend church. Members of the American community of fashion elite feel more comfortable and at home in Rome and Paris than they do in Akron or Bakersfield. They are more sympathetic to Islamic insurgents overseas than they are to tax protestors at home.

A certain small number of Americans (myself and a number of the contributors to Maggie’s Farm are typical) have a foot in both camps, having acquired elite educations and expensive tastes, but somehow mysteriously having avoided complete assimilation to haute bourgeois liberalism. From our uniquely privileged perspective, it is exceptionally clear just how deep, and how bitter, the recent new class divisions really are.

It isn’t only, as Anne Applebaum notes, that the upper middle class and ordinary middle class have become increasingly distinct and different. They now really detest one another.

19 Sep 2011

Tyler Durden responds to President Obama’s “Millionaire Tax” proposal.

In his increasingly desperate attempts to pander to a population that has by now entirely given up on the hope, and barely has any change left, Obama is going for broke (or technically the reverse) by setting the class warfare bar just that little bit higher. This time around, his targets are millionaires, who according to the NYT are about to see their taxes soar. Or not: nobody really knows if the proposed “Buffett Rule”, affectionately known for crony communist #1, will impact just millionaires income tax, which incidentally is the same as what everyone else is paying, or, far more importantly, their Investment Income, which is where the bulk of America’s wealthy income comes from. Which incidentally makes all the sense in the world: two and a half years after Bernanke has been desperately doing everything in his power to raise the “wealth effect” if only for the richest 1% of the US population, it is, from the government’s perspective, time for the taxman to come knocking and demand his share of the capital gains. Yet what is lost in this ridiculous proposal are the unintended consequences…

Read the whole thing.

There isn’t any hope that Obama can get these kinds of proposals through Congress. What this is all about is testifying aloud in public to his fidelity to the leftist redistributionist faith and energizing his base of parasites and looters.

23 Jul 2011

Angelo M. Codevilla, in the American Spectator, describes the great division in American society between the rulers and the ruled, explains how someone like Barack Obama can make a career as a professional Alinskyite agitator while remaining a member in good standing of the establishment elite, and addresses the dilemma of the oppressed “country class:” how does a Burkean class, conservative in temperament and habits, finding itself revolutionized over a substantial period of time make its own revolution?

Today’s ruling class, from Boston to San Diego, was formed by an educational system that exposed them to the same ideas and gave them remarkably uniform guidance, as well as tastes and habits. These amount to a social canon of judgments about good and evil, complete with secular sacred history, sins (against minorities and the environment), and saints. Using the right words and avoiding the wrong ones when referring to such matters — speaking the “in” language — serves as a badge of identity. Regardless of what business or profession they are in, their road up included government channels and government money because, as government has grown, its boundary with the rest of American life has become indistinct. Many began their careers in government and leveraged their way into the private sector. Some, e.g., Secretary of the Treasury Timothy Geithner, never held a non-government job. Hence whether formally in government, out of it, or halfway, America’s ruling class speaks the language and has the tastes, habits, and tools of bureaucrats. It rules uneasily over the majority of Americans not oriented to government. …

Who are these rulers, and by what right do they rule? How did America change from a place where people could expect to live without bowing to privileged classes to one in which, at best, they might have the chance to climb into them? What sets our ruling class apart from the rest of us?

The most widespread answers — by such as the Times’s Thomas Friedman and David Brooks — are schlock sociology. Supposedly, modern society became so complex and productive, the technical skills to run it so rare, that it called forth a new class of highly educated officials and cooperators in an ever less private sector. Similarly fanciful is Edward Goldberg’s notion that America is now ruled by a “newocracy”: a “new aristocracy who are the true beneficiaries of globalization — including the multinational manager, the technologist and the aspirational members of the meritocracy.” In fact, our ruling class grew and set itself apart from the rest of us by its connection with ever bigger government, and above all by a certain attitude. …

Professional prominence or position will not secure a place in the class any more than mere money. In fact, it is possible to be an official of a major corporation or a member of the U.S. Supreme Court (just ask Justice Clarence Thomas), or even president (Ronald Reagan ), and not be taken seriously by the ruling class. Like a fraternity, this class requires above all comity — being in with the right people, giving the required signs that one is on the right side, and joining in despising the Outs. Once an official or professional shows that he shares the manners, the tastes, the interests of the class, gives lip service to its ideals and shibboleths, and is willing to accommodate the interests of its senior members, he can move profitably among our establishment’s parts. …

Its attitude is key to understanding our bipartisan ruling class. Its first tenet is that “we” are the best and brightest while the rest of Americans are retrograde, racist, and dysfunctional unless properly constrained. …

Our ruling class’s agenda is power for itself. While it stakes its claim through intellectual-moral pretense, it holds power by one of the oldest and most prosaic of means: patronage and promises thereof. Like left-wing parties always and everywhere, it is a “machine,” that is, based on providing tangible rewards to its members. Such parties often provide rank-and-file activists with modest livelihoods and enhance mightily the upper levels’ wealth. Because this is so, whatever else such parties might accomplish, they must feed the machine by transferring money or jobs or privileges — civic as well as economic — to the party’s clients, directly or indirectly. This, incidentally, is close to Aristotle’s view of democracy. Hence our ruling class’s standard approach to any and all matters, its solution to any and all problems, is to increase the power of the government — meaning of those who run it, meaning themselves, to profit those who pay with political support for privileged jobs, contracts, etc. Hence more power for the ruling class has been our ruling class’s solution not just for economic downturns and social ills but also for hurricanes and tornadoes, global cooling and global warming. A priori, one might wonder whether enriching and empowering individuals of a certain kind can make Americans kinder and gentler, much less control the weather. But there can be no doubt that such power and money makes Americans ever more dependent on those who wield it. …

By taxing and parceling out more than a third of what Americans produce, through regulations that reach deep into American life, our ruling class is making itself the arbiter of wealth and poverty. While the economic value of anything depends on sellers and buyers agreeing on that value as civil equals in the absence of force, modern government is about nothing if not tampering with civil equality. By endowing some in society with power to force others to sell cheaper than they would, and forcing others yet to buy at higher prices — even to buy in the first place — modern government makes valuable some things that are not, and devalues others that are. Thus if you are not among the favored guests at the table where officials make detailed lists of who is to receive what at whose expense, you are on the menu. Eventually, pretending forcibly that valueless things have value dilutes the currency’s value for all.

Laws and regulations nowadays are longer than ever because length is needed to specify how people will be treated unequally. For example, the health care bill of 2010 takes more than 2,700 pages to make sure not just that some states will be treated differently from others because their senators offered key political support, but more importantly to codify bargains between the government and various parts of the health care industry, state governments, and large employers about who would receive what benefits (e.g., public employee unions and auto workers) and who would pass what indirect taxes onto the general public. The financial regulation bill of 2010, far from setting univocal rules for the entire financial industry in few words, spends some 3,000 pages (at this writing) tilting the field exquisitely toward some and away from others.

Read the whole thing.

30 Jun 2011

Repair Man Jack is fed up with democrat class warfare efforts at distraction.

If the majority of Americans really and truly believe that cutting the size of government, when struggling under $14Tr of national debt, equates to a desire to snuff puppies, we deserve a national default. If the majority of Americans truly believe they have a right to extract a loan for their tuition costs out of some other person’s paycheck, America is massively overdue for a well-deserved 2nd Great Depression. If the majority of people really believe the National Weather Service won’t just hire replacements from Korea or China; where students go to class at college sober, they are in for a grievous upset and disappointment.

Read the whole thing.

Hat tip to Jim Geraghty.

12 Jun 2011

There must be something special in the water of certain small towns, like Cape Girardeau, Missouri, where guys like Rush Limbaugh and Terry Teachout come from, and Shenandoah, Pennsylvania, where I grew up, that immunizes people from there who move away to the bright lights of the big city from becoming brainwashed and totally absorbed into the community of fashion which loves big cities and itself and loathes and despises ordinary small town America.

Terry Teachout is a rara avis, an astonishing intellectual polymath who knows everything about music and the arts and who also writes seriously on politics. Terry is the unusual intellectual Bohemian, who works harder than any Wall Street Law firm associate, writing articles and books and, for a number of years, working as the Wall Street Journal’s drama critic.

Someone like Terry would typically be expected to take the New Yorker magazine’s point of view that Manhattan is the center of the universe surrounded by an insignificant cultural wasteland, some fortunate few of whose unhappy natives succeed in escaping to the metropolis.

Terry Teachout has got to be the only major professional critic in New York who would say anything like this:

I left my home town a few months after graduating from high school in 1974, and since then I’ve only returned as a visitor. Not so David, my younger brother, who chose to settle in Smalltown, U.S.A., and has never lived anywhere else. He and his wife live three blocks from my mother’s house. If there’s such a thing as a model citizen, he fills the bill with room to spare. Among countless other valuable things, he’s served two terms on the city council and is a member of the board of trustees of his church, and whenever anyone in Smalltown now has occasion to mention the name “Teachout,” they usually mean him, not me.

I’m proud of my brother’s achievements, and more than a little bit jealous of them. In particular I envy his deep roots in the soil of Smalltown. I can’t claim to feel that way about New York City, where I’ve lived for the past quarter-century but to which I have no special attachment save for my love of certain people who live there.

For me, “home” is where Mrs. T is, and that changes from day to day. We moved to a new apartment last November, but we’ve spent so little time there that most of our belongings are still packed in cardboard boxes. So far this year we’ve “lived” in upper Manhattan, rural Connecticut, various parts of Florida, and a string of hotel rooms in Chicago, San Diego, and Washington, D.C. Right now we’re in Smalltown, but we’ll be driving up to St. Louis on Thursday, and a week and a half after that we’ll be on our way to Pittsburgh.

Truth to tell, I’m about as close to rootless as you can get, and because I come from Smalltown, where people tend as a rule to grow where they’re planted and stay where they’re put, this rootlessness has always seemed strange to me. I ought to feel at home somewhere or other, but when I moved away in 1974, I lost the sense of belonging that I possessed throughout the first eighteen years of my life, and since then I’ve never managed to recapture it.

This came as a surprise to me. I always figured I’d find a job in town, marry a Smalltown girl, start a family, and become a pillar of the community. My brother did those things, but I pulled up stakes and became a rambling man, moving from city to city in search of an identity that it took me the better part of a lifetime to find, insofar as I can be said to have found it. At various times in my life I expected to become a concert violinist, a lawyer, a high school teacher, and a psychotherapist, none of which I ended up doing. Instead I’ve paid the rent by working as a bank teller, a jazz bassist, a magazine editor, an editorial writer, a biographer, and a drama critic.

My brother and I, in short, have both led typical American lives. It is fully as American to stick close to home as it is to become a wanderer, but it’s the wanderers who get most of the press, perhaps because we’re the ones who write it–and I’m not so sure it should be that way. I left home to find myself, but my brother didn’t have to leave home because he knew who he was. I call my mother every night, but he sees her every day. I write books, but he has a grown daughter. I like to think that my work may ultimately prove to have some lasting value, but I’m sure that he’s done more to make the world a better place.

Read the whole thing.

—————————–

I understand Terry’s point of view perfectly. I’m another of the smart, bookish kids who went away to college and did not come back. In my case, my hometown was dwindling into a ghost town (that’s what happens to mining towns when the industry dies), and there isn’t even a there anymore that anyone could go back to.

I’ve always been aware that I was better read, more widely informed, and had found wider horizons for myself and developed a lot more expensive tastes than the people I grew up with, but I also remain conscious that I never had to go to work in the breakers as a schoolboy or risk my life everyday in the mines to support a family. I’ve never deluded myself into believing that being luckier, more affluent, and liking foreign films translates into making somebody a higher level of being.

13 May 2011

Walter Russell Mead, writing in the American Interest, though a classic representative of the liberal elite, is increasingly uneasy about his own class’s characterstic contempt for their fellow citizens, attitudes of self-entitlement, anti-patriotism, and aversion of self-doubt.

To listen to many bien pensant American intellectuals and above-the-salt journalists, America faces a shocking problem today: the cluelessness, greed, arrogance and bigotry of the American public. American elites are genuinely and sincerely convinced that the American masses don’t understand the world, don’t realize that American exceptionalism is a mental disease, want infinite government benefits while paying zero tax, and cling to their Bibles and their guns despite all the peer reviewed social science literature that demonstrates the danger and the worthlessness of both. …

But by historical standards, the average American is actually ahead of his or her ancestors. Today’s average Americans are smarter, more sophisticated, better educated, less racist and more tolerant than ever before. Immigrants face less prejudice in the United States than ever before in our history. Religious, ethnic and sexual minorities are more free to live their own lives more openly with less fear than ever before. There is more respect for science and learning, more openness to the arts and more interest in the viewpoints of other countries and cultures among Americans at large than in any past generation.

The American people aren’t perfect yet and never will be — but by the standards that matter to the Establishment, this is the best prepared, most open minded and most socially liberal generation in history. …

By contrast, we have never had an Establishment that was so ill-equipped to lead. It is the Establishment, not the people, that is falling down on the job.

Here in the early years of the twenty-first century, the American elite is a walking disaster and is in every way less capable than its predecessors. It is less in touch with American history and culture, less personally honest, less productive, less forward looking, less effective at and less committed to child rearing, less freedom loving, less sacrificially patriotic and less entrepreneurial than predecessor generations. Its sense of entitlement and snobbery is greater than at any time since the American Revolution; its addiction to privilege is greater than during the Gilded Age and its ability to raise its young to be productive and courageous leaders of society has largely collapsed. …

Many problems troubling America today are rooted in the poor performance of our elite educational institutions, the moral and social collapse of our ‘best’ families and the culture of narcissism and entitlement that has transformed the American elite into a flabby minded, strategically inept and morally confused parody of itself. Probably the best depiction of our elite in popular culture is the petulantly narcissistic Prince Charming in Shrek 2; our educational institutions are like the Fairy Godmother, weaving shoddy, cheap, feel-good illusions into a gossamer tissue of flattering lies. …

Some of the problem is intellectual. For almost a century now, American intellectual culture has been dominated by the values and legacy of the progressive movement. Science and technology would guide impartial experts and civil servants to create a better and better society. For most of the American elite today, progress means ‘progressive’; the way to make the world better is through more nanny state government programs administered by more, and more highly qualified, lifetime civil servants. Anybody who doubts this is a reactionary and an ignoramus. This isn’t just a rational conviction with much of our elite; it is a bone deep instinct. Unfortunately, the progressive tradition no longer has the answers we need, but our leadership class by and large cannot think in any other terms.

The old ideas don’t work anymore, but the elite hates the thought of change.

Past generations of the American elite were always a little bit nervous about their situation; it is morally difficult for an elite based on birth, ethnicity or wealth to justify itself in a country with the universalist, democratic values of the United States. The tendency of American life is always to erode the power and prestige of elites; populism is the direction in which America likes to travel. Past generations of elites were conflicted about their status and struggled against a sense that it was somehow un-American to set yourself up as better than other people.

The increasingly meritocratic elite of today has no such qualms. The average Harvard Business School and Yale Law School graduate today feels that privilege has been earned. Didn’t he or she score higher on the LSATs than anyone else? Didn’t he or she previously pass the rigorous scrutiny of the undergraduate admissions process in a free and fair process to get into a top college? Haven’t they been certified as the best of the best by impartial experts?

A guilty elite may be healthier for society than a self-righteous one.

Read the whole thing.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Class Warfare' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|