Guilty Meritocrats

City versus Country, Class, Economics, Education, Meritocracy

The big think piece of the week is this exercise in class navel-gazing in the Atlantic. Its author, Matthew Stewart, is an obviously Very Smart Guy, who went to Princeton and Oxford and who’s written books on the American Revolution’s foundation in Philosophy and on why Management Consulting is typically a scam.

I’ve joined a new aristocracy now, even if we still call ourselves meritocratic winners. If you are a typical reader of The Atlantic, you may well be a member too. (And if you’re not a member, my hope is that you will find the story of this new class even more interesting—if also more alarming.) To be sure, there is a lot to admire about my new group, which I’ll call—for reasons you’ll soon see—the 9.9 percent. We’ve dropped the old dress codes, put our faith in facts, and are (somewhat) more varied in skin tone and ethnicity. People like me, who have waning memories of life in an earlier ruling caste, are the exception, not the rule.

By any sociological or financial measure, it’s good to be us. It’s even better to be our kids. In our health, family life, friendship networks, and level of education, not to mention money, we are crushing the competition below. But we do have a blind spot, and it is located right in the center of the mirror: We seem to be the last to notice just how rapidly we’ve morphed, or what we’ve morphed into.

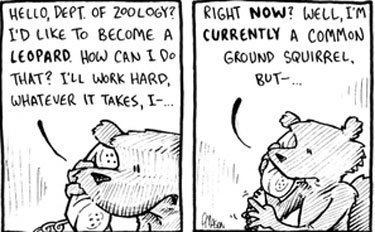

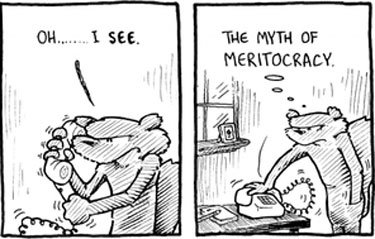

The meritocratic class has mastered the old trick of consolidating wealth and passing privilege along at the expense of other people’s children. We are not innocent bystanders to the growing concentration of wealth in our time. We are the principal accomplices in a process that is slowly strangling the economy, destabilizing American politics, and eroding democracy. Our delusions of merit now prevent us from recognizing the nature of the problem that our emergence as a class represents. We tend to think that the victims of our success are just the people excluded from the club. But history shows quite clearly that, in the kind of game we’re playing, everybody loses badly in the end. …

The fact of the matter is that we have silently and collectively opted for inequality, and this is what inequality does. It turns marriage into a luxury good, and a stable family life into a privilege that the moneyed elite can pass along to their children. How do we think that’s going to work out?

This divergence of families by class is just one part of a process that is creating two distinct forms of life in our society. Stop in at your local yoga studio or SoulCycle class, and you’ll notice that the same process is now inscribing itself in our own bodies. In 19th-century England, the rich really were different. They didn’t just have more money; they were taller—a lot taller. According to a study colorfully titled “On English Pygmies and Giants,†16-year-old boys from the upper classes towered a remarkable 8.6 inches, on average, over their undernourished, lower-class countrymen. We are reproducing the same kind of division via a different set of dimensions.

Obesity, diabetes, heart disease, kidney disease, and liver disease are all two to three times more common in individuals who have a family income of less than $35,000 than in those who have a family income greater than $100,000. Among low-educated, middle-aged whites, the death rate in the United States—alone in the developed world—increased in the first decade and a half of the 21st century. Driving the trend is the rapid growth in what the Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton call “deaths of despairâ€â€”suicides and alcohol- and drug-related deaths.

The sociological data are not remotely ambiguous on any aspect of this growing divide. We 9.9 percenters live in safer neighborhoods, go to better schools, have shorter commutes, receive higher-quality health care, and, when circumstances require, serve time in better prisons. We also have more friends—the kind of friends who will introduce us to new clients or line up great internships for our kids.

These special forms of wealth offer the further advantages that they are both harder to emulate and safer to brag about than high income alone. Our class walks around in the jeans and T‑shirts inherited from our supposedly humble beginnings. We prefer to signal our status by talking about our organically nourished bodies, the awe-inspiring feats of our offspring, and the ecological correctness of our neighborhoods. We have figured out how to launder our money through higher virtues.

Most important of all, we have learned how to pass all of these advantages down to our children. In America today, the single best predictor of whether an individual will get married, stay married, pursue advanced education, live in a good neighborhood, have an extensive social network, and experience good health is the performance of his or her parents on those same metrics.

We’re leaving the 90 percent and their offspring far behind in a cloud of debts and bad life choices that they somehow can’t stop themselves from making. We tend to overlook the fact that parenting is more expensive and motherhood more hazardous in the United States than in any other developed country, that campaigns against family planning and reproductive rights are an assault on the families of the bottom 90 percent, and that law-and-order politics serves to keep even more of them down. We prefer to interpret their relative poverty as vice: Why can’t they get their act together?

Stewart’s mea culpa article is intelligent and well-written, but gravely flawed by many of the characteristic intellectual errors of the meritocratic community of fashion elite.

It’s true that life in America has changed. Economic, regional, and cultural changes enormously increased social and physical mobility over much of the last century, killed local industries, and drained, year after year, ever larger percentages of people with brains and talent and initiative out American small towns and rural counties, sending them off to the big cities and their posh suburbs.

The automobile and the shopping mall killed Main Street, and the big multiplex theaters killed the hometown movie palace. Now Amazon is killing off the malls, and digital streaming off the Internet is killing off the multiplexes.

It is characteristic of members of the intelligentsia like Matthew Stewart to place limitless confidence in the calculative powers of human reason and the wisdom of credentialed experts and to imagine that the iron laws of economics and the choices of the gods of History can simply be set aside by the application of a bit of collectivist statism. That perspective is obviously dead wrong.

Unless you are prepared to go to the same lengths as Pol Pot and march people at gunpoint out of the city and into the countryside again, you are not going to change all this. A hundred years ago, many people were sad that the gods of Economics had decreed that the small family farm had to die and everyone had to move into town and take work at the factory or the mill, but it happened, and that is how economies progress and standards of living rise. But change always comes with some pain as its cost.

The establishmentarian feels guilty and suffers from an obsession with Equality. People like Matthew Stewart naturally believe that they are the cat’s pajamas, the winners in Life’s Olympic Race, and they assume that everybody is crying himself to sleep every night for not being one of them.

They are profoundly wrong in a couple of ways. First of all, it is possible to be a good man and a person of accomplishment and skill in all sorts of ways not measured by the SATs and entirely unconnected to graduation from elite schools or the publication of important books. There are circumstances in life in which you’d be better off having the assistance of a skilled automobile mechanic or a grizzled old hunting guide than that of an Oxford graduate or best-selling historian.

Then, it is also an important fact of life that it is simply impossible for everybody in the world to graduate from a top Ivy League school and grow up to be a doctor, lawyer, investment banker, or management consultant. The world really does have to have more Indians than chiefs. And not everybody thinks the same way. I have some things in common with Mr. Stewart: I went to Yale and I sometimes read The Atlantic. But they’d have to pay me by the hour to live in Brookline or any similar place. And I’m surrounded out here in rural Pennsylvania by people who feel the same way.

My Trump-voting neighbors here in the Central Pennsylvania boondocks are, it’s true, ill-educated, and unfashionable. They are also a lot less affluent than people like Mr. Stewart. They do have some problems, but most of them, at least most of the older ones, are not unhappy. I think younger people out here in the sticks are more decidedly the left-behinds, and are more demoralized by the decay of Religion and the local economy, and the weakening of all the institutions. And it is there, not in the areas Mr. Stewart talks about, that we meritocrats are to blame.

If you go to Princeton or Yale, you can reject bourgeois society, organized Religion, and Kipling’s gods of the copybook headings and (mostly) get away with it. You’re a clever person and probably a strong-willed person, so you can do drugs and get up and go to work anyway. You believe in free love, but somehow in the end, you wind up married anyway. But where we catch a cold, the ordinary people back home get the Plague. Without the old-time Religion and conventional bourgeois morality keeping them on the straight and narrow, for them, everything goes to shit. You get single mothers, jailbird fathers dead at 35 from booze or meth or crashed cars, neglected, badly-raised kids, and ruined lives all over the place.

Our guilt does not lie in erecting barriers to entry at Ivy League schools. Our class’s guilt lies in our snobbery, our boundless self-entitlement, and our abandonment of hometowns, home regions, and obligations of leadership and fellowship, in our home communities, and in the deplorable example we set with our wholesale rejection of tradition and conventional wisdom.