Category Archive 'Horatio Nelson'

21 Oct 2018

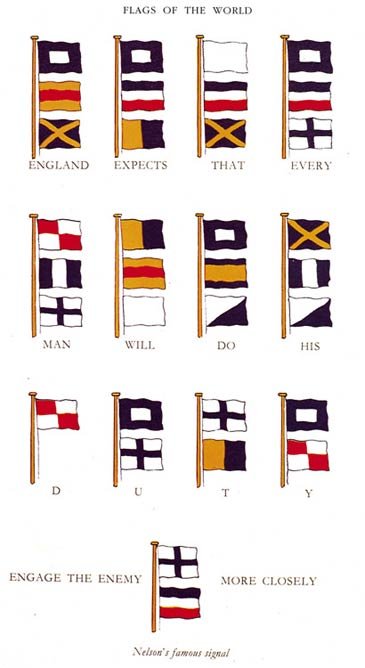

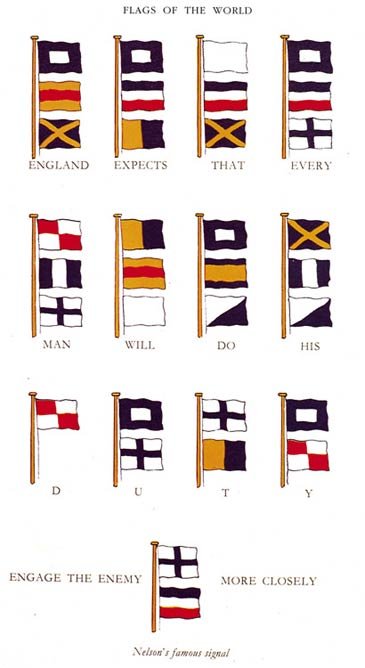

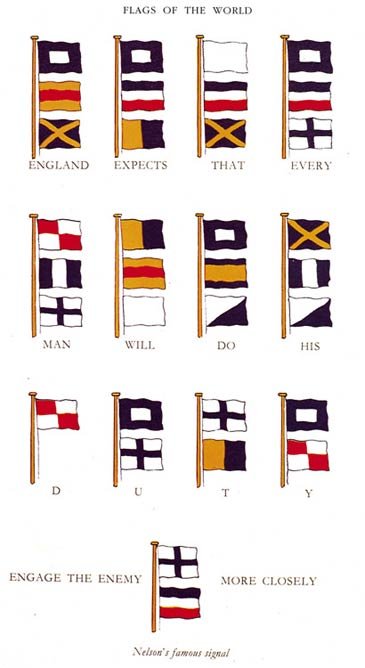

Sent at 11:45 A.M., just as Nelson’s two parallel columns of ships prepared to break through the French & Spanish line.

Wikipedia:

At four o’clock in the morning of 21 October Nelson ordered the Victory to turn towards the approaching enemy fleet, and signaled the rest of his force to battle stations. He then went below and made his will, before returning to the quarterdeck to carry out an inspection. Despite having 27 ships to Villeneuve’s 33, Nelson was confident of success, declaring that he would not be satisfied with taking fewer than 20 prizes. He returned briefly to his cabin to write a final prayer, after which he joined Victory’s signal lieutenant, John Pasco.

Mr Pasco, I wish to say to the fleet “England confides that every man will do his duty”. You must be quick, for I have one more signal to make, which is for close action.

Pasco suggested changing ‘confides’ to ‘expects’, which being in the Signal Book, could be signalled by the use of a single flag, whereas ‘confides’ would have to spelt out letter by letter. Nelson agreed, and the signal was hoisted.

As the fleets converged, the Victory’s captain, Thomas Hardy suggested that Nelson remove the decorations on his coat, so that he would not be so easily identified by enemy sharpshooters. Nelson replied that it was too late ‘to be shifting a coat’, adding that they were ‘military orders and he did not fear to show them to the enemy’. Captain Henry Blackwood, of the frigate HMS Euryalus, suggested Nelson come aboard his ship to better observe the battle. Nelson refused, and also turned down Hardy’s suggestion to let Eliab Harvey’s HMS Temeraire come ahead of the Victory and lead the line into battle.

Victory came under fire, initially passing wide, but then with greater accuracy as the distances decreased. A cannonball struck and killed Nelson’s secretary, John Scott, nearly cutting him in two. Hardy’s clerk took over, but he too was almost immediately killed. Victory’s wheel was shot away, and another cannonball cut down eight marines. Hardy, standing next to Nelson on the quarterdeck, had his shoe buckle dented by a splinter. Nelson observed ‘this is too warm work to last long’. The Victory had by now reached the enemy line, and Hardy asked Nelson which ship to engage first. Nelson told him to take his pick, and Hardy moved Victory across the stern of the 80-gun French flagship Bucentaure. Victory then came under fire from the 74-gun Redoutable, lying off the Bucentaure’s stern, and the 130-gun SantÃsima Trinidad. As sharpshooters from the enemy ships fired onto Victory’s deck from their rigging, Nelson and Hardy continued to walk about, directing and giving orders.

Shortly after one o’clock, Hardy realised that Nelson was not by his side. He turned to see Nelson kneeling on the deck, supporting himself with his hand, before falling onto his side. Hardy rushed to him, at which point Nelson smiled

Hardy, I do believe they have done it at last… my backbone is shot through.

He had been hit by a marksman from the Redoutable, firing at a range of 50 feet (15 m). The bullet had entered his left shoulder, passed through his spine at the sixth and seventh thoracic vertebrae, and lodged two inches (5 cm) below his right shoulder blade in the muscles of his back.

Nelson was carried below by sergeant-major of marines Robert Adair and two seamen. As he was being carried down, he asked them to pause while he gave some advice to a midshipman on the handling of the tiller. He then draped a handkerchief over his face to avoid causing alarm amongst the crew. He was taken to the surgeon William Beatty, telling him

You can do nothing for me. I have but a short time to live. My back is shot through.

Nelson was made comfortable, fanned and brought lemonade and watered wine to drink after he complained of feeling hot and thirsty. He asked several times to see Hardy, who was on deck supervising the battle, and asked Beatty to remember him to Emma, his daughter and his friends.

Hardy came belowdecks to see Nelson just after half-past two, and informed him that a number of enemy ships had surrendered. Nelson told him that he was sure to die, and begged him to pass his possessions to Emma. With Nelson at this point were the chaplain Alexander Scott, the purser Walter Burke, Nelson’s steward, Chevalier, and Beatty. Nelson, fearing that a gale was blowing up, instructed Hardy to be sure to anchor. After reminding him to “take care of poor Lady Hamilton”, Nelson said “Kiss me, Hardy”. Beatty recorded that Hardy knelt and kissed Nelson on the cheek. He then stood for a minute or two before kissing him on the forehead. Nelson asked, “Who is that?”, and on hearing that it was Hardy, he replied “God bless you, Hardy.” By now very weak, Nelson continued to murmur instructions to Burke and Scott, “fan, fan … rub, rub … drink, drink.” Beatty heard Nelson murmur, “Thank God I have done my duty”, and when he returned, Nelson’s voice had faded and his pulse was very weak. He looked up as Beatty took his pulse, then closed his eyes. Scott, who remained by Nelson as he died, recorded his last words as “God and my country”. Nelson died at half-past four, three hours after he had been shot.

Coloured engraving by J. Heath after Benjamin West, The death of Lord Nelson aboard HMS Victory at the battle of Trafalgar, 1811.

12 Jan 2018

At Sotheby’s London, “Of Royal and Noble Descent” Auction, Lot 116:

AN EXCEPTIONALLY LARGE FRAGMENT OF THE UNION FLAG, BELIEVED TO HAVE FLOWN FROM HMS VICTORY AT THE BATTLE OF TRAFALGAR

comprising eight panels of red, white and blue hand-woven woollen bunting, hand-stitched together to form part of the bottom-right (or top-left) quadrant of the Union flag, hemmed at the bottom (or top), hem turned over enclosing c.460mm of twine, crudely torn at the edges, c.860 x 920 mm, mounted, framed, and glazed (frame size 1125 x 1125mm), c.1801-1805

AN EVOCATIVE AND IMPRESSIVE RELIC OF NELSON AND TRAFALGAR. Nelson’s ships sailed into battle at Trafalgar flying the national flag rather than just their squadron colours, as a result of an order issued by Nelson in the days before the battle: “When in the presence of an Enemy, all the Ships under my command are to bear white Colours [i.e. St George’s Ensign], and a Union Jack is to be suspended from the fore top-gallant stay” (10 October 1805). HMS Victory consequently flew two Union flags and a St George’s Ensign, which were returned to England with the ship and the body of Nelson.

These battle ensigns, unique patriotic mementoes of Nelson’s final and greatest victory, were later woven into the solemn and dignified series of ceremonials that marked his state funeral in January 1806. The body lay in state at the Painted Hall at Greenwich for four days before processing upriver in a funeral barge with a flotilla of naval escorts, disembarking at Whitehall Stairs and resting overnight in the Admiralty. The following day, 9 January, a vast procession followed Nelson’s remains to St Paul’s Cathedral, the site of the funeral. Incorporated into the funeral cortege was a group of 48 seamen and Marines from HMS Victory, who bore with them the ship’s three battle ensigns and were, according to one eyewitness, “repeatedly and almost continually cheered as they passed along”. At the conclusion of the funeral service, with the coffin placed at the heart of the cathedral beneath Wren’s great dome, the sailors were supposed to fold the flags and place them reverently on the coffin. The conclusion of the service, in fact, played out rather differently, as described by the Naval Chronicle (1806): “the Comptroller, Treasurer and Steward of his Lordship’s household then broke their staves, and gave the pieces to Garter, who threw then into the grave, in which all the flags of the Victory, furled up by the sailors were deposited – These brave fellows, however, desirous of retaining some memorials of their great and favourite commander, had torn off a considerable part of the largest flag, of which most of them obtained a portion.” According to one acute observer: “That was Nelson: the rest was so much the Herald’s office.” (See The Nelson Companion, ed. White (1995), pp8-14)

Most of the surviving fragments of the Victory’s flags are much smaller than the current piece. Small fragments of white and blue bunting, no more than 12cm in length, have appeared at auction (e.g. Bonhams, 28 September 2004, lot 117; Sotheby’s, 17 December 2009, lot 9) and other similar fragments are found at the National Maritime Museum and other institutional collections. Only two complete Union jacks that were used as battle ensigns at Trafalgar survive: one from HMS Minotaur (National Maritime Museum), the other from HMS Spartiate (sold at auction by Charles Miller Ltd., 21 October 2009, lot 53, £384,000).

Estimate: 80,000 — 100,000 GBP — 105,376 – 131,720 USD

24 Aug 2017

How much longer will Christopher Columbus look out over New York’s Columbus Circle?

New York Post:

Mayor de Blasio opened a historical can of worms Tuesday in his quest to rid the city of offensive monuments, ducking for cover when asked if Grant’s Tomb might be shuttered because of actions two centuries ago.

The mayor had no ready answers when pounded with questions about flawed historical figures, from Ulysses S. Grant to little-known former New York Gov. Horatio Seymour, who are being honored in the city.

Grant issued an order to expel Jews from three states during the Civil War while Seymour’s campaign slogan in 1868 was “This is a White Man’s Country; Let White Men Rule.â€

Monuments to Christopher Columbus have also sparked criticism over his treatment of native populations.

“We’re trying to unpack 400 years of American history here — that’s really what’s going on,†de Blasio said defensively.

“This is complicated stuff. But you know it’s a lot better to be talking about it and trying to work through it than ignoring it because I think for a lot of people in this city and in this country, they feel that their history has been ignored or affronts to their history have been tolerated.â€

Hizzoner at one point acknowledged he hadn’t considered whether the review should include portraits until the one of Seymour hanging inside City Hall was mentioned.

He also couldn’t say whether school names or other dedications would be reconsidered.

“To some extent the commission’s going to have to figure out what are the appropriate boundaries,†de Blasio said. “We may end up doing this in stages because this is complex stuff.â€

———————————

In the Guardian, Afua Hirsch is demanding that Britain follow the American example and remove Lord Nelson from his column in Trafalgar Square. Sure, Nelson won the battles of the Nile, Copenhagen, and Trafalgar, and prevented a Napoleonic Invasion of England, but, hey! what about the black contribution to British history?

We have “moved on†from this era no more than the US has from its slavery and segregationist past. The difference is that America is now in the midst of frenzied debate on what to do about it, whereas Britain – in our inertia, arrogance and intellectual laziness – is not.

The statues that remain are not being “put in their historical contextâ€, as is often claimed. Take Nelson’s column. Yes, it does include the figure of a black sailor, cast in bronze in the bas-relief. He was probably one of the thousands of slaves promised freedom if they fought for the British military, only to be later left destitute, begging and homeless, on London’s streets when the war was over.

But nothing about this “context†is accessible to the people who crane their necks in awe of Nelson. The black slaves whose brutalisation made Britain the global power it then was remain invisible, erased and unseen.

The people so energetically defending statues of Britain’s white supremacists remain entirely unconcerned about righting this persistent wrong. They are content to leave the other side of the story where it is now – in Nelson’s case, among the dust and the pigeons, 52 metres below the admiral’s feet. The message seems to be that is the only place where the memory of the black contribution to Britain’s past belongs.

30 May 2015

This is the bullet which killed Admiral Horatio Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805.

Wikipedia:

At four o’clock in the morning of 21 October Nelson ordered the Victory to turn towards the approaching enemy fleet, and signalled the rest of his force to battle stations. He then went below and made his will, before returning to the quarterdeck to carry out an inspection. Despite having 27 ships to Villeneuve’s 33, Nelson was confident of success, declaring that he would not be satisfied with taking fewer than 20 prizes. He returned briefly to his cabin to write a final prayer, after which he joined Victory’s signal lieutenant, John Pasco.

Mr Pasco, I wish to say to the fleet “England confides that every man will do his duty”. You must be quick, for I have one more signal to make, which is for close action.

Pasco suggested changing ‘confides’ to ‘expects’, which being in the Signal Book, could be signalled by the use of a single flag, whereas ‘confides’ would have to spelt out letter by letter. Nelson agreed, and the signal was hoisted.

As the fleets converged, the Victory’s captain, Thomas Hardy suggested that Nelson remove the decorations on his coat, so that he would not be so easily identified by enemy sharpshooters. Nelson replied that it was too late ‘to be shifting a coat’, adding that they were ‘military orders and he did not fear to show them to the enemy’. Captain Henry Blackwood, of the frigate HMS Euryalus, suggested Nelson come aboard his ship to better observe the battle. Nelson refused, and also turned down Hardy’s suggestion to let Eliab Harvey’s HMS Temeraire come ahead of the Victory and lead the line into battle.

Victory came under fire, initially passing wide, but then with greater accuracy as the distances decreased. A cannonball struck and killed Nelson’s secretary, John Scott, nearly cutting him in two. Hardy’s clerk took over, but he too was almost immediately killed. Victory’s wheel was shot away, and another cannonball cut down eight marines. Hardy, standing next to Nelson on the quarterdeck, had his shoe buckle dented by a splinter. Nelson observed ‘this is too warm work to last long’. The Victory had by now reached the enemy line, and Hardy asked Nelson which ship to engage first. Nelson told him to take his pick, and Hardy moved Victory across the stern of the 80-gun French flagship Bucentaure. Victory then came under fire from the 74-gun Redoutable, lying off the Bucentaure’s stern, and the 130-gun SantÃsima Trinidad. As sharpshooters from the enemy ships fired onto Victory’s deck from their rigging, Nelson and Hardy continued to walk about, directing and giving orders.

Shortly after one o’clock, Hardy realised that Nelson was not by his side. He turned to see Nelson kneeling on the deck, supporting himself with his hand, before falling onto his side. Hardy rushed to him, at which point Nelson smiled

Hardy, I do believe they have done it at last… my backbone is shot through.

He had been hit by a marksman from the Redoutable, firing at a range of 50 feet (15 m). The bullet had entered his left shoulder, passed through his spine at the sixth and seventh thoracic vertebrae, and lodged two inches (5 cm) below his right shoulder blade in the muscles of his back.

Nelson was carried below by sergeant-major of marines Robert Adair and two seamen. As he was being carried down, he asked them to pause while he gave some advice to a midshipman on the handling of the tiller. He then draped a handkerchief over his face to avoid causing alarm amongst the crew. He was taken to the surgeon William Beatty, telling him

You can do nothing for me. I have but a short time to live. My back is shot through.

Nelson was made comfortable, fanned and brought lemonade and watered wine to drink after he complained of feeling hot and thirsty. He asked several times to see Hardy, who was on deck supervising the battle, and asked Beatty to remember him to Emma, his daughter and his friends.

Hardy came belowdecks to see Nelson just after half-past two, and informed him that a number of enemy ships had surrendered. Nelson told him that he was sure to die, and begged him to pass his possessions to Emma. With Nelson at this point were the chaplain Alexander Scott, the purser Walter Burke, Nelson’s steward, Chevalier, and Beatty. Nelson, fearing that a gale was blowing up, instructed Hardy to be sure to anchor. After reminding him to “take care of poor Lady Hamilton”, Nelson said “Kiss me, Hardy”. Beatty recorded that Hardy knelt and kissed Nelson on the cheek. He then stood for a minute or two before kissing him on the forehead. Nelson asked, “Who is that?”, and on hearing that it was Hardy, he replied “God bless you, Hardy.” By now very weak, Nelson continued to murmur instructions to Burke and Scott, “fan, fan … rub, rub … drink, drink.” Beatty heard Nelson murmur, “Thank God I have done my duty”, and when he returned, Nelson’s voice had faded and his pulse was very weak. He looked up as Beatty took his pulse, then closed his eyes. Scott, who remained by Nelson as he died, recorded his last words as “God and my country”. Nelson died at half-past four, three hours after he had been shot.

Coloured engraving by J. Heath after Benjamin West, The death of Lord Nelson aboard HMS Victory at the battle of Trafalgar, 1811.

Hat tip to Ratak Monodosico.

22 Oct 2014

Sent at 11:45 A.M., just as Nelson’s two parallel columns of ships prepared to break through the French & Spanish line.

22 Oct 2014

Carried by Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar, 21 October 1805. Because fighting aboard ships was likely to occur in confined spaces, Naval officers were more likely to carry a hanger (a short hunting-style sword) into battle, rather than a full-length sword.

Via Ratak Monodosico.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Horatio Nelson' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|