Category Archive 'Individualism'

12 Mar 2021

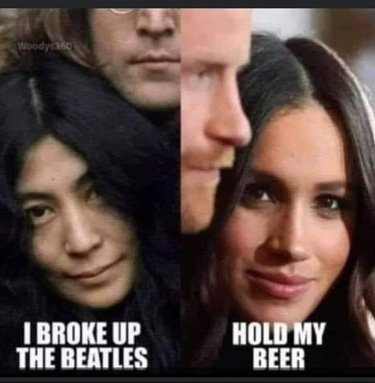

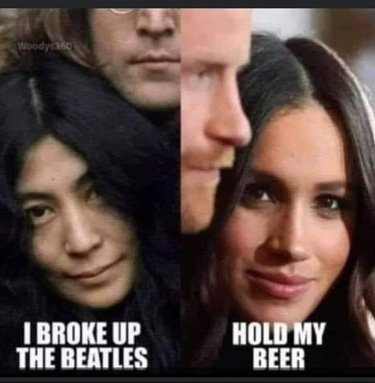

Ron Liddle, in the UK Spectator, looks disfavorably on the Duke and Duchess of Netflix and Oprah to boot.

The USA is the least communalistic and most individualistic nation of any on Earth. It is written into their Declaration of Independence that an individual’s right to the pursuit of happiness trumps, if I can use the word, every other consideration. It is all a little alien to us over here in Britain, which is one reason why we tend to find Meghan Markle a repulsive creature. What the ghastly Oprah Winfrey and indeed Hillary Clinton do not understand is that if there was any resentment towards Meghan in the UK, it was not because she is of mixed race, but because she is American and behaves like a caricature of a particularly stupid American. The color of her skin matters not a jot: it is the noisome ordure which spews out of her mouth on a daily basis that grates. Again, the narcissism and self-obsession and the acquired victimhood, the vapid and banal attempts at self-justification.

The American insistence on the primacy of the individual also explains Meghan’s different interpretation of two words which we, over here, think we understand clearly: ‘duty’ and ‘truth’. When her idiot husband was told he would not be getting back his honorary military ranks, the two of them (i.e. Meghan) released an emetic statement to the press suggesting that there were many ways one might perform one’s duties. No. Duty is something imposed and involves self-sacrifice, discipline and obedience. It does not mean doing what the hell you like, which is what the two of them have done. But if you are a country which doubts the validity of a communal ethos of ‘duty’, then Meghan’s standpoint is one you may well arrive at, especially if you are not terribly bright.

Similarly, Markle was asked about ‘her’ truth. People don’t have their own truth. There is truth and there is falsehood, and there’s an end to it. But once more, the native ideology devolves the concept of truth down to the individual level, regardless of whether it is truth at all. It is from America that we have imported the morally and rationally bereft progressive ideology that insists that if people feel they have been victimized, then they have been. And that everybody can be whatever they want to be, regardless of the facts. Elevate the individual — beyond reason, beyond government, beyond God — and this is what you get: a D-list sleb who married well thinking she has been victimized and is in possession of a ‘truth’ which runs counter to the truth.

The cultural divide broadens still further when we consider Oprah Winfrey, one of America’s greatest mysteries. But boy, does she have hauteur and dominion. It is very difficult for us to understand why the Yanks so revere the woman. She is an appalling interviewer, seemingly utterly incurious, every question submitted for approval and the answers rehearsed over and over again. Ill-informed, incapable of asking an interesting question, always slightly more regal than whoever it is she is interviewing. There is no intellect on display, just a perpetual desire to paddle about in the shallows, or indeed barely skim the surface, of the subjects before her. But then she subscribes to the same inane ideology — that Meghan Markle has a truth that is equally valid to the truth, and who is she to question that validity? Anti-journalism. It was rumored she might one day run for office. I think she’d be perfect for the East and West Coast voters, a conduit of witless acceptance of every meaningless liberal shibboleth to which those deluded people subscribe.

RTWT

I think he’s perfectly right in despising these people’s attitudes, but I think his notions of “individualism vs. communalism” are wildly inaccurate.

The older America was, as Tocqueville noted, both enormously individualistic, but also intensely dutiful and civic-minded. No one would have accused, for instance, Davy Crockett and Jim Bowie of a lack of individualism, but both were perfectly prepared to give their lives for the liberty of their countrymen.

What’s wrong with Meghan, Oprah, et. al. isn’t rugged individualism, their afflictions are infantilism, narcissism, self-entitlement, and sanctimony. Meghan and Oprah are selfish, it’s true, but they are also among the least individualistic, the most tediously conformist people in the world.

12 Nov 2019

David Noonan, in Scientific American, surprisingly enough, has positive things to say about the influence of Christianity and the Church of Rome on Western Civilization.

Perhaps even more surprisingly, this article treats Individualism as a positive and implicitly acknowledges the inferiority of other cultures.

In what may come as a surprise to freethinkers and nonconformists happily defying social conventions these days in New York City, Paris, Sydney and other centers of Western culture, a new study traces the origins of contemporary individualism to the powerful influence of the Catholic Church in Europe more than 1,000 years ago, during the Middle Ages.

According to the researchers, strict church policies on marriage and family structure completely upended existing social norms and led to what they call “global psychological variation,†major changes in behavior and thinking that transformed the very nature of the European populations.

The study, published this week in Science, combines anthropology, psychology and history to track the evolution of the West, as we know it, from its roots in “kin-based†societies. The antecedents consisted of clans, derived from networks of tightly interconnected ties, that cultivated conformity, obedience and in-group loyalty—while displaying less trust and fairness with strangers and discouraging independence and analytic thinking.

The engine of that evolution, the authors propose, was the church’s obsession with incest and its determination to wipe out the marriages between cousins that those societies were built on. The result, the paper says, was the rise of “small, nuclear households, weak family ties, and residential mobility,†along with less conformity, more individuality, and, ultimately, a set of values and a psychological outlook that characterize the Western world. The impact of this change was clear: the longer a society’s exposure to the church, the greater the effect.

Around A.D. 500, explains Joseph Henrich, chair of Harvard University’s department of human evolutionary biology and senior author of the study, “the Western church, unlike other brands of Christianity and other religions, begins to implement this marriage and family program, which systematically breaks down these clans and kindreds of Europe into monogamous nuclear families. And we make the case that this then results in these psychological differences.â€

In their comparison of kin-based and church-influenced populations, Henrich and his colleagues identified significant differences in everything from the frequency of blood donations to the use of checks (instead of cash) and the results of classic psychology tests—such as the passenger’s dilemma scenario, which elicits attitudes about telling a lie to help a friend. They even looked at the number of unpaid parking tickets accumulated by delegates to the United Nations.

“We really wanted to combine the kinds of measures that psychologists use, that give you some control in the lab, with real-world measures,†Henrich says. “We really like the parking tickets. We get the U.N. diplomats from around the world all in New York City and see how they behave.â€

The policy has since changed, but for years diplomats who parked illegally were not required to pay the tickets the police wrote. In their analysis of those tickets, the researchers found that over the course of one year, diplomats from countries with higher levels of “kinship intensityâ€â€”the prevalence of clans and very tight families in a society—had many more unpaid parking tickets than those from countries without such history. Diplomats from Sweden and Canada, for example, had no outstanding tickets in the period studied, while unpaid parking tickets per diplomat were about 249 for Kuwait, 141 for Egypt and 126 for Chad. Henrich attributes this phenomenon to the insular mind-set that is characteristic of intense kinship.

While it builds a close and very cooperative group, that sense of cooperation does not carry beyond the group. “The idea is that you are less concerned about strangers, people you don’t know, outsiders,†he says.

The West itself is not uniform in kinship intensity. Working with cousin-marriage data from 92 provinces in Italy (derived from church records of requests for dispensations to allow the marriages), the researchers write, they found that “Italians from provinces with higher rates of cousin marriage take more loans from family and friends (instead of from banks), use fewer checks (preferring cash), and keep more of their wealth in cash instead of in banks, stocks, or other financial assets.†They were also observed to make fewer voluntary, unpaid blood donations.

In the course of their research, Henrich and his colleagues created a database and calculated “the duration of exposure†to the Western church for every country in the world, as well as 440 “subnational European regions.†They then tested their predictions about the influence of the church at three levels: globally, at the national scale; regionally, within European countries; and among the adult children of immigrants in Europe from countries with varying degrees of exposure to the church.

RTWT

The thesis of this study, unfortunately, is a classic case of mechanistic scientism. It would make much more sense to point out that Christianity fosters Individualism through ideas, that recognition of the value of the human individual is rooted in Christianity’s teaching that everyone has a soul and consequently possesses human dignity, and that each individual needs to pursue his soul’s salvation.

29 Nov 2015

Rod Dreher posts a letter from an anonymous (and not entirely grammatical) conservative college professor.

[W]hen people my parents’ age scoff at the whole trans thing and dismiss it as just the cause du jour (remember Darfur? neither do any of the SJWs), I shake my head and tell them they have no idea what’s coming. The project of the Willed Self is a natural outgrowth of Enlightenment thinking. (I share your opinion that Submission is not a great book, but a very important one in terms of exposing the internal contradictions of the Enlightenment.) The whole intellectual movement of the last three centuries has at its core the principle of freeing the willed self from all constraints. The trans movement represents this idea’s apex: if we can free ourselves from basic biology and anatomy, then truly we have become gods. “I am that I am†is no longer confined to Exodus 3; it is the mantra of the willed self freed from all external barriers. There is nothing beyond the subjective, the personal, the therapeutic, because all that matters is how I define my own self, my own existence, and my own gratification. There can be no society or community within this worldview. Patrick Deneen was right in that “After Liberalism†lecture he gave: Enlightenment liberalism has been scary for we [sic] traditional conservatives, but what’s coming next — what’s coming now — is terrifying.

15 Oct 2015

In the New Yorker, Kathryn Schulz looks at Henry David Thoreau through the lenses of contemporary leftist community of fashion ideology, and does not like what she sees. Thoreau may have been keen on Abolition, but he is not a leftist radical at all. He is a shameless individualist, and if you look closely enough, eeek! he is liable to remind you of Ayn Rand.

The real Thoreau was, in the fullest sense of the word, self-obsessed: narcissistic, fanatical about self-control, adamant that he required nothing beyond himself to understand and thrive in the world. From that inward fixation flowed a social and political vision that is deeply unsettling. It is true that Thoreau was an excellent naturalist and an eloquent and prescient voice for the preservation of wild places. But “Walden†is less a cornerstone work of environmental literature than the original cabin porn: a fantasy about rustic life divorced from the reality of living in the woods, and, especially, a fantasy about escaping the entanglements and responsibilities of living among other people. …

Thoreau went to Walden, he tells us, “to learn what are the gross necessaries of lifeâ€: whatever is so essential to survival “that few, if any, whether from savageness, or poverty, or philosophy, ever attempt to do without it.†Put differently, he wanted to try what we would today call subsistence living, a condition attractive chiefly to those not obliged to endure it. It attracted Thoreau because he “wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life.†Tucked into that sentence is a strange distinction; apparently, some of the things we experience while alive count as life while others do not. In “Walden,†Thoreau made it his business to distinguish between them.

As it turns out, very little counted as life for Thoreau. Food, drink, friends, family, community, tradition, most work, most education, most conversation: all this he dismissed as outside the real business of living. Although Thoreau also found no place in life for organized religion, the criteria by which he drew such distinctions were, at base, religious. A dualist all the way down, he divided himself into soul and body, and never could accept the latter. “I love any other piece of nature, almost, better,†he confided to his journal. The physical realities of being human appalled him. “The wonder is how they, how you and I, can live this slimy, beastly life, eating and drinking,†he wrote in “Walden.†Only by denying such appetites could he feel that he was tending adequately to his soul.

“Walden,†in consequence, is not a paean to living simply; it is a paean to living purely, with all the moral judgment that the word implies. In its first chapter, “Economy,†Thoreau lays out a program of abstinence so thoroughgoing as to make the Dalai Lama look like a Kardashian. (That chapter must be one of the highest barriers to entry in the Western canon: dry, sententious, condescending, more than eighty pages long.) Thoreau, who never wed, regarded “sensuality†as a dangerous contaminant, by which we “stain and pollute one another.†He did not smoke and avoided eating meat. He shunned alcohol, although with scarcely more horror than he shunned every beverage except water: “Think of dashing the hopes of a morning with a cup of warm coffee, or of an evening with a dish of tea! Ah, how low I fall when I am tempted by them!†Such temptations, along with the dangerous intoxicant that is music, had, he felt, caused the fall of Greece and Rome.

I cannot idolize anyone who opposes coffee. …

Unsurprisingly, this thoroughgoing misanthrope did not care to help other people. “I confess that I have hitherto indulged very little in philanthropic enterprises,†Thoreau wrote in “Walden.†He had “tried it fairly†and was “satisfied that it does not agree with my constitution.†Nor did spontaneous generosity: “I require of a visitor that he be not actually starving, though he may have the very best appetite in the world, however he got it. Objects of charity are not guests.†In what is by now a grand American tradition, Thoreau justified his own parsimony by impugning the needy. “Often the poor man is not so cold and hungry as he is dirty and ragged and gross. It is partly his taste, and not merely his misfortune. If you give him money, he will perhaps buy more rags with it.†Thinking of that state of affairs, Thoreau writes, “I began to pity myself, and I saw that it would be a greater charity to bestow on me a flannel shirt than a whole slop-shop on him.â€

The poor, the rich, his neighbors, his admirers, strangers: Thoreau’s antipathy toward humanity even encompassed the very idea of civilization. In his journals, he laments the archeological wealth of Great Britain and gives thanks that in New England “we have not to lay the foundation of our houses in the ashes of a former civilization.†That is patently untrue, but it is also telling: for Thoreau, civilization was a contaminant. “Deliver me from a city built on the site of a more ancient city, whose materials are ruins, whose gardens cemeteries,†he wrote in “Walden.†“The soil is blanched and accursed there.†Seen by these lights, Thoreau’s retreat at Walden was a desperate compromise. What he really wanted was to be Adam, before Eve—to be the first human, unsullied, utterly alone in his Eden. …

Thoreau never understood that life itself is not consistent—that what worked for a well-off Harvard-educated man without dependents or obligations might not make an ideal universal code.) Those failings are ethical and intellectual, but they are also political. To reject all certainties but one’s own is the behavior of a zealot; to issue contradictory decrees based on private whim is that of a despot.

This is not the stuff of a democratic hero. Nor were Thoreau’s actual politics, which were libertarian verging on anarchist. Like today’s preppers, he valued self-sufficiency for reasons that were simultaneously self-aggrandizing and suspicious: he did not believe that he needed anything from other people, and he did not trust other people to provide it. “That government is best which governs least,†Jefferson supposedly said. Thoreau, revising him, wrote, “That government is best which governs not at all.â€

Yet for a man who believed in governance solely by conscience, his own was frighteningly narrow. Thoreau had no understanding whatsoever of poverty and consistently romanticized it. (“Farmers are respectable and interesting to me in proportion as they are poor.â€) His moral clarity about abolition stemmed less from compassion or a commitment to equality than from the fact that slavery so blatantly violated his belief in self-governance. Indeed, when abolition was pitted against rugged individualism, the latter proved his higher priority. “I sometimes wonder that we can be so frivolous, I may almost say,†he writes in “Walden,†“as to attend to the gross but somewhat foreign form of servitude called Negro Slavery, there are so many keen and subtle masters that enslave both North and South. It is hard to have a Southern overseer; it is worse to have a Northern one; but worst of all when you are the slave-driver of yourself.” …

Although Thoreau is often regarded as a kind of cross between Emerson, John Muir, and William Lloyd Garrison, the man who emerges in “Walden†is far closer in spirit to Ayn Rand: suspicious of government, fanatical about individualism, egotistical, élitist, convinced that other people lead pathetic lives yet categorically opposed to helping them. It is not despite but because of these qualities that Thoreau makes such a convenient national hero. …

[T]he mature position, and the one at the heart of the American democracy, seeks a balance between the individual and the society. Thoreau lived out that complicated balance; the pity is that he forsook it, together with all fellow-feeling, in “Walden.†And yet we made a classic of the book, and a moral paragon of its author—a man whose deepest desire and signature act was to turn his back on the rest of us.

Read the whole thing.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Individualism' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|