Warner Bwothers’ Wascals Were Wefties!

Bugs Bunny, Gay Marriage, James Lileks, Satire, Warner Brothers Cartoons

James Lileks defends the classic Warner brothers cartoons against an attack in (now wanting to charge you money) STALE magazine by LGBTQ-expert Mark Joseph Stern bemoaning how brutal the old cartoons were and finding their comedic violence “appallingly macabre” by noting just how ahead-of-their-time Bugs, Elmer, Daffy and the rest were in championing self-construction of identity and same-sex marriage.

Slate came up with a piece called “Looney Tunes cartoons were more brutal than you remember,â€* which concludes:

But no kids’ show today would ever treat firearms or gun deaths so lightly, with such zany exuberance, as Looney Tunes once did. That jaunty disregard of the consequences of violence is part of what made the show so bizarrely delightful. In a post-Newtown world, however, what was once strangely funny now registers as appallingly macabre.

Yes —- if you’ve had your sense of humor surgically removed, and replaced with an oversized gland that produces chemicals responsible for compulsive frowning. Otherwise you might continue to find them strangely funny, oddly funny, audaciously funny, or perhaps just hilarious. There are still some, I hope, who can smile at the sight of Daffy’s beak blown clear around to the other side of his head after Fudd loosed a blunderbuss blast. There is no pain involved; only irritation and annoyance. He readjusts his beak with an audible squeaking sound, and stomps off to yell at Bugs, instigator of the incident.

But that very episode — “Duck! Rabbit, Duck!†— contains messages that should hearten the heart of a Slate writer, for it contains a very modern message about identity. As you may recall, the plot concerns Fudd’s confusion over which season it is: Wabbit, or Duck? The signage is confusing. Daffy self-identifies as a duck, and this being the ’40s, he is locked in a fixed identity, a product of a culture that says if it walks like a duck and talks like a duck it is a duck. But as we now know, “species†is as fluid as any other form of identity.

And that’s something Bugs reveals in a very subversive sequence. Daffy uses colloquial expressions to describe his mood, noting that he feels like a goat. Whereupon Bugs produces a sign that says it is Goat Season. Fudd unloads accordingly. It may look like violence. But it’s really acceptance. If Daffy says he is a goat then he is a goat. He may suffer the consequences, but Fudd has affirmed his statement of identity. Over the course of the cartoon Daffy identifies with various species, and in each instance Bugs has an appropriate placard to nudge Fudd toward accepting the fluid spectrum on which Daffy may choose to locate himself.

Half a century before Facebook’s 57 genders, Warner Brothers was laying the groundwork.

It’s not an isolated example of progressive themes in Looney Tunes. “Hillbilly Hare†contains a wealth of sociological insight. The main characters are two rural archetypes mired in poverty, wandering the backwoods shoeless, engaged in a pointless blood feud. You could almost call it “What’s the Matter with the Ozarks,†for instead of concentrating their enmity against the 1 percent that has exploited their labor and resources, they are pitted against each other in a pointless struggle.

Into this world comes Bugs, who draws their attention by dressing up as a seductive female rabbit — a transgressive statement that manages to lampoon heteronormative behavior (transgender Bugs feigns interest in the males) and reinforces the worst sort of cross-dressing stereotypes, as female-identified Bugs is all lipstick and hip-cocking sashay exaggeration. But for the time it was groundbreaking. To a youth who sat in the theater in 1948 it may have said, Yes, it is possible to break the confines of biological gender, and to do so with such confidence and style that people who would otherwise fricassee you for supper would follow your every suggestion.

And what a suggestion! In a hilarious set piece, Bugs calls a square-dance tune whose instructions aren’t the usual do-si-do, bow-to-your-left, but consist entirely of commands to inflict escalating levels of retributive violence. The men, socially and culturally conditioned to follow any command the square-dance caller makes, are not only helpless to assert their own will, they end up dancing with each other. This redefines the courtship ritual of the dance — a means of channeling and controlling sexual energy — into a fiercely homoerotic ballet.

“Hit ’im again, the critter ain’t dead.†It’s safe to assume Bugs is talking about the stifling hand of religious intolerance and centuries of marriage inequality. With a tidy couplet he brushes away the pope’s objections: Promenade like a bride and groom, he calls, and that they do. …

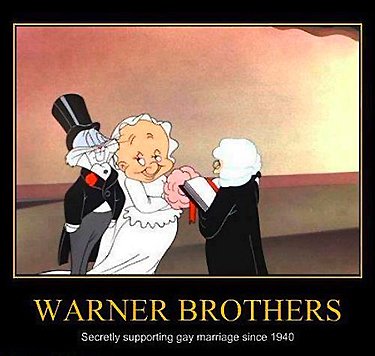

Bugs would return to the idea of same-sex marriage in one of the most popular and enduring cartoons, the one based on the “Barber of Seville.†While most of the cartoon involves the usual violence — much of which seems macabre and inappropriate in light of the fact that someone could be murdered at La Scala, some day — it ends with the whirlwind courtship of Bugs and Fudd. They point guns of increasing size at each other, a metaphor for the escalating divisions of contemporary politics — but Bugs utterly defuses the situation by presenting Fudd with flowers, and Elmer promptly changes into a wedding dress.

If ever there was a marvelous rendition of the swiftness with which the debate on marriage equality changed, it’s that. Granted, Bugs picks up Elmer and drops him from a great height, but the course of true love never did run smoothly.

Read the whole thing.

——————————

——————————