Originally published 24 April 2009.

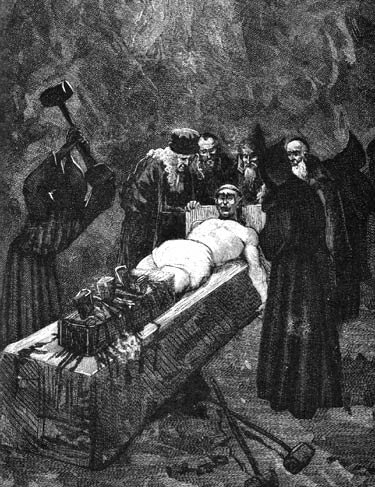

Real torture, a very different thing from the infliction of mild and temporary discomfort or a slap.

Torture

[adopted from the French torture (12th century Dictionnaire général de la langue français Hatzfeld & Darmesteter, 1890-1900), adaptation of Latin tortura twisting, wreathing, torment, torture; from torquēre, tort- to twist, to torment]

1. The infliction of excruciating pain, as practised by cruel tyrants, savages, brigands, etc. from a delight in watching the agony of a victim, in hatred or revenge, or as a means of extortion; specifically judicial torture, inflicted by a judicial or quasi-judicial authority, for the purpose of forcing an accused or suspected person to confess, or an unwilling witness to to give evidence or information; a form of this (often in plural). To put to (the) torture, to inflict torture upon, to torture. …

historical examples of usage omitted

2. Severe or excruciating pain or suffering of mind or body; anguish, agony, torment; the infliction of such. …

figurative meanings omitted

— Oxford English Dictionary, 1971, p. 3357.

————————————————-

The left has loudly and persistently accused the Bush Administration of violating International Law, the US Constitution, the Geneva Convention, and conventional standards of human decency by torturing detainees.

These accusations have been advanced by a large variety of allied voices at every level of print and electronic publication employing the same inflammatory characterizations, the same reliance on preassumed conclusions, and the same intimidating tone of exaggerated emotionalism.

The left’s punditocracy naturally avoids ever questioning whether modest forms of coercion, such as waterboarding, slaps to the face or abdomen, sleep deprivation, and deliberately-caused temperature discomfort, etc., carefully and deliberately calculated to stop short of inflicting any enduring harm to the subject, actually do rise to the level of meeting the normal (non-figurative) definition of torture.

A slap to the face may be painful, humiliating, and unpleasant, but it is really “excruciating” or “severe?” Most of us (of the older generation, at least) actually have been slapped in the face in childhood by other children and even by adults. My elementary school principal did not like an angry letter to the editor about her school policies I had composed in the 8th grade and slapped me across the face. I can’t say that I ever thought of myself as a torture victim or an appropriate case for an investigation by some International Committee on Human Rights.

When I read over the list of coercive measures sanctioned by the Bush Administration for use in extracting information from only three of the most important participants in a conspiracy which brought about the violent deaths of more than 3000 innocent American civilians and which was actively in the process attempting further such attacks on an even greater scale, most of them remind me of the ordinary cruelties inflicted on small children commonly by schoolyard bullies.

Waterboarding amounts to the victim being briefly deprived of breath by facial immersion in an attempt to use fear of drowning to compel cooperation. Is there really anyone in America who didn’t have his or her head held underwater at least once by a larger bully or childhood playmate?

Abu Zubaydah was placed by CIA interrogators into close propinquity with a caterpillar. I’m afraid that when I search my own conscience I can recall dropping a caterpillar down the back of at least one female classmate back in the third grade myself.

The controversial coercive interrogation methods were employed by the Bush Administration against, we must remember, only three spectacularly guilty murderers whose hands were dripping with innocent blood, and were clearly not excruciating. They were capable of, and intended to, induce discomfort, probably even anguish, but not agony.

Severe is a relative term, I suppose. But, in the context of forcible interrogation, surely a severe form of coercion would be a practice capable of producing permanent injury or death.

What traditionally defined real torture, more specifically than the OED’s definition, was the permanence of the result. Someone would not be refered to as “tortured,” who had been beaten up or simply slapped around. A person referred to as having been tortured would have to have suffered, at the very least, lasting serious injury.

Torture has always conceptually involved pieces of one’s anatomy being cut or burned, fingernails pulled out, bones broken, and joints dislocated. Having your head dunked or your face slapped or being confronted by a caterpillar may be unpleasant, but only in the context of figurative speech is it torture.

A common perspective on the subject is that real torture has to include an ultimate threat of ending with death. The audience finds credible this viewpoint as illustrated in the 1941 John Huston film version of The Maltese Falcon.

Sam Spade finding himself unarmed in the presence of Caspar Guttman and his criminal allies successfully defies threats of torture because his adversaries can’t afford to kill him.

Joel Cairo: You seem to forget that you are not in a position to insist upon anything.

Caspar Cuttman: Now, come, gentlemen. Let’s keep our discussion on a friendly basis.

There certainly is something in what Mr. Cairo said…

Sam Spade: If you kill me, how are you gonna get the bird? If I know you can’t afford to kill me, how’ll you scare me into giving it to you?

Caspar Guttman: Sir, there are other means of persuasion besides killing and threatening to kill.

Sam Spade: Yes, that’s…That’s true. But none of them are any good unless the threat of death is behind them.

You see what I mean?

If you start something, I’ll make it a matter of your having to kill me or call it off.

Caspar Guttman: That’s an attitude, sir, that calls for the most delicate judgement on both sides. Because, as you know, in the heat of action, men are likely to forget where their best interests lie, and let their emotions carry them away.

Look at the first definition again. The coercive tactics employed by the Bush Administration did not produce “excruciating pain.” The US Administration was not a cruel tyranny (whatever the infantile left may chose to think). Our intelligence officers were not savages or brigands, though the three interrogation subjects certainly were. The discomforts inflicted on the three interrogation subjects were not done out of hatred or revenge, but to protect innocent lives. The only small portion of the Oxford Dictionary’s definition which fits is the purpose of causing unwilling witnesses to provide information. But that is only a descriptive portion of the definition, and the vital and key “excruciating pain” element of the definition is completely missing.

QED: The coercive tactics employed by the Bush Administration against three Al Qaeda detainees were not torture, not by the best dictionary definition of the word, and not by our conventional “ordinary language” understanding of the meaning of the word.