Category Archive 'Paleography'

11 Jul 2021

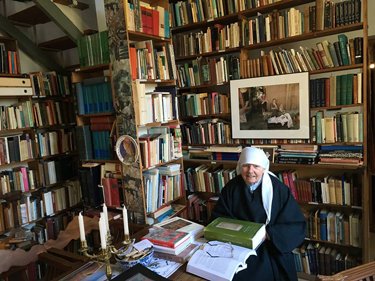

Julia Bolton Holloway, Hermit, Scholar, Custodian of Florence’s Victorian ‘English’ Cemetery.

Most news reports are behind paywalls, but the Daily Mail comes through for us again:

A handwritten manuscript by Dante Alighieri, author of the Divine Comedy, Italy’s ‘national poet’ and father of modern Italian, has been discovered by a nun.

Dante was born in 1265 in Florence and was instrumental in establishing the literature of Italy, but nobody has seen his handwriting in centuries.

This new discovery was found by a Florence-based researcher turned nun, who claims to have stumbled on the work hidden away in two libraries, according to a report in The Times.

They date to his time as a student in Florence when he was copying out works on the art of government, and were found in both Florence and the Vatican.

Julia Bolton Holloway taught Medieval studies at Princeton University in New Jersey, before becoming a nun and running the English cemetery in Florence.

She said the writing was ‘schoolboy-like’ but in excellent Tuscan, which provided the blueprint for Italian and covers ideas that show up in Divine Comedy.

RTWT

21 Jun 2021

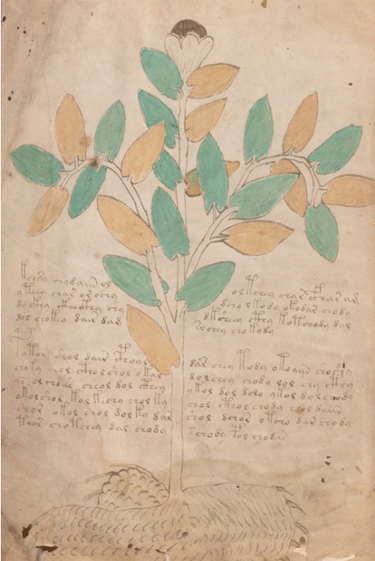

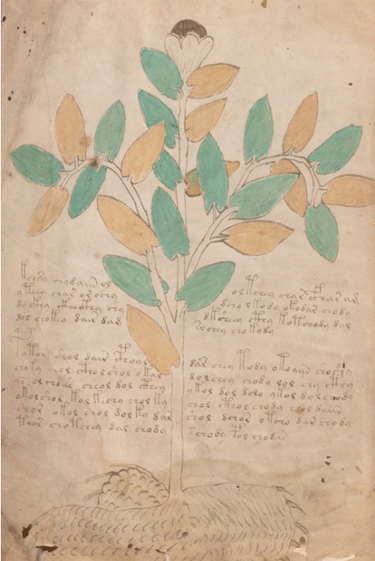

Gerard E. Cheshire, in a new paper on Academia.edu: “Voicing the Voynich: The Pronuncial Writing System and Graeco-Iberian Language of MS408 (Ischia/Voynich),” claims to have identified the language Yale’s Voynich Manuscript is written in, and proposes a methodology for readers to employ and join in to help compete its decipherment.

This paper provides more precise guidance and instruction with regard to the palaeographic method in translating manuscript MS408 (Ischia, Voynich). Manuscripts of antiquity typically require palaeographic interpretive techniques for the purpose of translation, because they include idiomatic abbreviations, unusual calligraphy, exotic language, unique letter symbols and so on, making them a challenge to read. Therefore, it is necessary to learn and understand the associated peculiarities of the MS408 language and writing system in order to arrive at reasonable translations.

This process requires historical and linguistic research, so that initial translation possibilities can be progressively honed by a process of elimination until the semantics and syntax are workable. This scientific approach ensures that the emergent translations are sufficiently refined to be as close a match as possible to the intended meaning of the text. Due to the mutable nature of palaeographic analysis, there is often room for continued adjustment in translation, so accuracy relies on reprocessing the text time and time again, until new passes offer no further improvement. Thus, by repetition of the procedure the translation becomes more and more precise by degrees: i.e. as near to 100% accuracy as possible.

Initially the language was thought to be an anachronistic or outdated form of proto-Romance, but further research has revealed the language to be the Medieval Iberian variant of Romance known as Galician-Portuguese (G-P), with the inclusion of some Latin, Greek and occasional Arabic. The writing system is phonetic but is heavily abbreviated with enclitics, clitics and plosives, so that silent and junctural consonants and vowels have often become omitted altogether. Thus, the text was written in direct imitation of speech rather than obeying rules of

spelling, grammar and punctuation – thus, it is a pronuncial writing system. In addition, Latin stock words and phrases are abbreviated to initial letters.

As the writing system is pronuncial the consistency seen in its idiosyncratic spelling, from one page to the next, suggests that all of the text was written by the same hand, simply because two or more authors would have arrived at two or more spelling methods, unless there was some agreement, or the scribes were being dictated to. As the text does seem to differ in style, this is a possible explanation, although individuals can and do vary in their handwriting from day to day.

Whichever explanation is correct, the author, or authors, of the manuscript evidently devised a unique writing system, which may have been due to absence of formal education, due to cultural isolation, or it may have been deliberate to keep the information away from male eyes, as it would have been deemed embarrassing due to courtly etiquette, because the contents largely refer to private womanly matters relating to seduction, impregnation, gestation, contraception, abortion, childbirth, gynaecology, paediatrics, medicines, astrology, supernatural beliefs, treatments, therapies, ageing, beautification, illness and death.

Ischia was home to a Greek diaspora population with its own Basilian Orthodox monastery and nunnery in the early 15th century, when the island and its citadel, Castello Aragonese, were appropriated by Alfonso V, of the Crown of Aragon, during his campaign to conquer nearby Naples. Thus, the Iberian language of the newcomers was mixed with the Graeco language of the islanders, resulting in the manuscript language, best described as Graeco-Iberian Romance.

Despite its close geographical proximity to Italy, the island of Ischia had been culturally discrete for centuries when the manuscript was written, and therefore had little linguistic commonality with the contemporaneous Neapolitan culture. The manuscript dates quite precisely because a narrative map within the manuscript describes and illustrates the rescue of islanders from Vulcano and Lipari, with a flotilla of ships from Ischia, following a volcanic eruption that began on the February 4th, 1444, and created the Vulcanello peninsula. The map lies between

Portfolios 86 and 87. …

This paper presents reworked and updated translations of the first lines of the manuscript plant pages 1-10 (Portfolios 2a-6b), so that the reader can see how the translation process is conducted and to encourage the reader to continue translating the pages, by employing deeper knowledge of the writing system, the language and historical botanical information, to arrive at the most cogent translations, based on semantics (meaning) and syntax (structure).

An algorithmic approach is first employed, whereby possible words are listed according to the priority array queue of Galician-Portuguese, Latin, Greek, Arabic. Due to their linguistic stem and cultural assimilation, similar words are also often found in other Iberian Romance languages: Valencian, Catalan, Occitan, Asturian, Aragonese. Many variants are also found in other Romance languages: Italian, Neapolitan, Sicilian, Corsican, Sardinian, Istriot, Ladin, Venetian,

Friulian, French, Romanian, Aromanian.

Cross-reference with historical botanical and medicinal information is then employed to arrive at the most logical semantics and syntax, so that the most likely translations are preserved, and the least likely translations are eliminated. By running sentences through this process a number of times, the translations are gradually perfected.

I’m not at all certain that he’s right, but his paper is intriguing.

————————–

Older description from Yale’s Beinecke Library:

Written in Central Europe at the end of the 15th or during the 16th century, the origin, language, and date of the Voynich Manuscript –named after the Polish-American antiquarian bookseller, Wilfrid M. Voynich, who acquired it in 1912– are still being debated as vigorously as its puzzling drawings and undeciphered text. Described as a magical or scientific text, nearly every page contains botanical, figurative, and scientific drawings of a provincial but lively character, drawn in ink with vibrant washes in various shades of green, brown, yellow, blue, and red.

Based on the subject matter of the drawings, the contents of the manuscript falls into six sections: 1) botanicals containing drawings of 113 unidentified plant species; 2) astronomical and astrological drawings including astral charts with radiating circles, suns and moons, Zodiac symbols such as fish (Pisces), a bull (Taurus), and an archer (Sagittarius), nude females emerging from pipes or chimneys, and courtly figures; 3) a biological section containing a myriad of drawings of miniature female nudes, most with swelled abdomens, immersed or wading in fluids and oddly interacting with interconnecting tubes and capsules; 4) an elaborate array of nine cosmological medallions, many drawn across several folded folios and depicting possible geographical forms; 5) pharmaceutical drawings of over 100 different species of medicinal herbs and roots portrayed with jars or vessels in red, blue, or green, oand 6) continuous pages of text, possibly recipes, with star-like flowers marking each entry in the margins.

16 Apr 2016

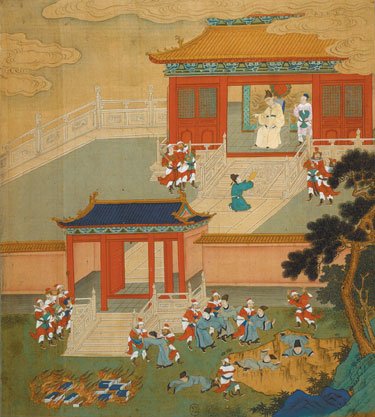

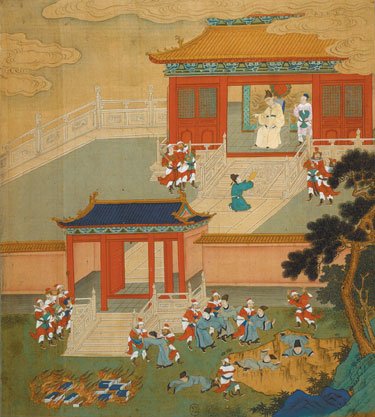

Emperor Ch’in Shih Huang Ti of the Ch’in dynasty ‘burning all the books and throwing scholars into a ravine’ in order to stamp out ideological nonconformity after the unification of China in 221 BC.

Ian Johnson reviews, in the New York Review of Books, Sarah Allan’s Buried Ideas: Legends of Abdication and Ideal Government in Early Chinese Bamboo-Slip Manuscripts, a study of ancient Chinese manuscripts written on bamboo slips containing the views of heretofore-unknown Ch’in-suppressed Chinese philosophic schools completely outside the familiar Confucian and Taoist traditions, views favoring meritocratic rather than hereditary dynastic government.

As Beijing prepared to host the 2008 Olympics, a small drama was unfolding in Hong Kong. Two years earlier, middlemen had come into possession of a batch of waterlogged manuscripts that had been unearthed by tomb robbers in south-central China. The documents had been smuggled to Hong Kong and were lying in a vault, waiting for a buyer.

Universities and museums around the Chinese world were interested but reluctant to buy. The documents were written on hundreds of strips of bamboo, about the size of chopsticks, that seemed to date from 2,500 years ago, a time of intense intellectual ferment that gave rise to China’s greatest schools of thought. But their authenticity was in doubt, as were the ethics of buying looted goods. Then, in July, an anonymous graduate of Tsinghua University stepped in, bought the soggy stack, and shipped it back to his alma mater in Beijing. …

The manuscripts’ importance stems from their particular antiquity. Carbon dating places their burial at about 300 BCE. This was the height of the Warring States Period, an era of turmoil that ran from the fifth to the third centuries BCE. During this time, the Hundred Schools of Thought arose, including Confucianism, which concerns hierarchical relationships and obligations in society; Daoism (or Taoism), and its search to unify with the primordial force called Dao (or Tao); Legalism, which advocated strict adherence to laws; and Mohism, and its egalitarian ideas of impartiality. These ideas underpinned Chinese society and politics for two thousand years, and even now are touted by the government of Xi Jinping as pillars of the one-party state.

The newly discovered texts challenge long-held certainties about this era. Chinese political thought as exemplified by Confucius allowed for meritocracy among officials, eventually leading to the famous examination system on which China’s imperial bureaucracy was founded. But the texts show that some philosophers believed that rulers should also be chosen on merit, not birth—radically different from the hereditary dynasties that came to dominate Chinese history. The texts also show a world in which magic and divination, even in the supposedly secular world of Confucius, played a much larger part than has been realized. And instead of an age in which sages neatly espoused discrete schools of philosophy, we now see a more fluid, dynamic world of vigorously competing views—the sort of robust exchange of ideas rarely prominent in subsequent eras.

These competing ideas were lost after China was unified in 221 BCE under the Qin, China’s first dynasty. In one of the most traumatic episodes from China’s past, the first Qin emperor tried to stamp out ideological nonconformity by burning books. … Modern historians question how many books really were burned. (More works probably were lost to imperial editing projects that recopied the bamboo texts onto newer technologies like silk and, later, paper in a newly standardized form of Chinese writing.) But the fact is that for over two millennia all our knowledge of China’s great philosophical schools was limited to texts revised after the Qin unification. Earlier versions and competing ideas were lost—until now.

Read the whole thing.

Hat tip to Belacqui.

29 Jan 2010

Osama is a warmist. I guess that figures.

Bad news for literature. Patrician Louis Auchincloss dies at 92 (WaPo obit), and Zen recluse J.D. Salinger passed away at 91 (London Times obit).

Bad news for scholarship. King’s College London is planning to eliminate Britain’s only chair in paleography. No money in that, you see.

Why so few conservative or libertarian academics? Two researchers propose “path dependence” as the explanation.

Five stages of democrat grief over the health care reform bill.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Paleography' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|