From Yale: Mixed News

Benjamin Franklin, College Masters, John C. Calhoun, Pauli Murray, Peter Salovey, Political Correctness, Racial Politics, Un Autre Jolie Cadeau de la Revolution Francaise, Yale

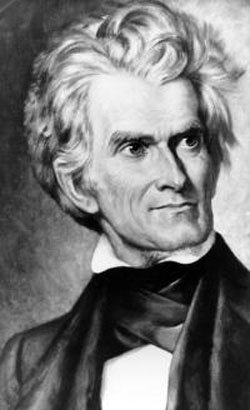

John Caldwell Calhoun; Y’ 1804; Vice President of the United States, 1825-1832; Secretary of State, 1844-1845; Secretary of War, 1817-1825; Senator from South Carolina, 1832-1843 and 1845-1850; Member House of Representatives representing 6th District of South Carolina, 1811-1817; Author, Disquisition on Government (1849), Discourse on the Constitution and Government of the United States (1851); defender of States’ Rights and proponent of the “Concurrent Majority” doctrine holding that minorities ought to have the right in extremis to block majority rule; and member of the all-time Great Triumvirate of the U.S. Senate.

1) Calhoun College stays Calhoun College.

Yale President Salovey announced yesterday afternoon, the Oldest College Daily reported, that the residential college named for Yale’s greatest political thinker and statesman would retain its name, despite John C. Calhoun having held, in the first half of the 19th century, positions on Slavery and inherent Racial Inferiority generally regarded with abhorrence today.

Salovey justified this decision on the part of the Administration and the Corporation, saying:

Removing Calhoun’s name obscures the legacy of slavery rather than addressing it. Erasing Calhoun’s name from a much-beloved residential college risks masking this past, downplaying the lasting effects of slavery and substituting a false and misleading narrative, albeit one that might allow us to feel complacent or, even, self-congratulatory.â€

I suspect that, unreported, unacknowledged, and unsung, somewhere in the decision-making meeting rooms in Woodbridge Hall a dramatic last stand was taken by someone on behalf on history, tradition, and sanity, and that there must have been some terrible threat of a grand financial legacy being withheld were Calhoun’s name to be removed.

——————————–

Master’s House, Trumbull College

2) The Title of “Master” of a Residential College Will Be Changed to “Head.”

Salovey wrote:

The use of “master†as a title at Yale is a legacy of the college systems at Oxford and Cambridge. The term derives from the Latin magister, meaning “chief, head, director, teacher,†and it appears in the titles of university degrees (master of arts, master of science, and others) and in many aspects of the larger culture (master craftsman, master builder). Some members of our community argued that discarding the term “master†would interject into an ancient collegiate tradition a racial narrative that has never been associated with its use in the academy. Others maintained that regardless of its history of use in the academy, the title—especially when applied to an authority figure—carries a painful and unwelcome connotation that can be difficult or impossible for some students and residential college staff to ignore.

Among the many comments considered on this matter, the thoughts and recommendations of the current Council of Masters, the twelve heads of the existing residential colleges, were especially salient. The council deliberated at length, informed by a multitude of discussions with students, staff, faculty, and fellows, as well as by reflections submitted to an online site open to all members of each residential college community. The council also monitored similar discussions at other colleges and universities, although its members were determined to arrive at their recommendations bearing in mind Yale’s distinctive traditions and culture.

The council found that making a recommendation to change the title was far from simple. People held a wide range of views, not as strongly correlated as some might have predicted with circumstances of age, race, or position in the college community. Nothing about the term itself is intrinsically tied to Yale’s history prior to 1930, or to the relationships that students of each generation have formed or will form with the individuals who lead their colleges. Moreover, a decision to stop using the term “master†does not compromise the study of larger historical issues. In short, the reasons to change the title of “master†proved more compelling than the reasons to keep it, and the current masters themselves no longer felt it appropriate to be addressed in that manner.

Not incidental to the discussion was the task of finding an alternative title that speaks to the definition and responsibilities of the office. In this respect, “head of college†is the most logical and straightforward choice. In its favor is that archival records show that “head†and “headship†were placeholders for the title in the original planning documents. Heads of college may be addressed as professor, doctor, or Mr. or Ms., as applicable or as they prefer.

Alumni, particularly those of Calhoun College, actually cared about their college’s name being changed. Nobody particularly cared about the Master title, so Master was obviously the perfect sacrifice to fling upon the PC bonfire to appease the mob.

Yalies tend to be pedantic and good at research, so one does wonder why Peter Salovey and his powers-that-be confreres did not trouble themselves to consider “Warden,” “Rector,” or even “President” (as at Magdalen College, Oxford), but instead followed sheepishly along in the lame footsteps of Harvard and Princeton in changing that title to “Head.” It rankles, I think, that the pathetic creature occupying the chair in which John Hersey once sat, set the contemptible policy which the entire set of residential college will be proceeding to follow.

——————————–

Benjamin West, Benjamin Franklin Drawing Electricity from the Sky, 1816, Philadelphia Museum of Art

3. The new residential colleges will be named for Benjamin Franklin and Pauli Murray (whoever the hell she is).

Peter Salovey explained:

Benjamin Franklin College will recognize the recipient of a Yale honorary degree (1753 Hon. M.A.) whose immense accomplishments span the arts, the sciences, government, and service to society. The 41 published volumes of his papers, which contain the record of Benjamin Franklin’s life correspondence, are among the Yale University Library’s most important collections. The Franklin Papers represent the work of many Yale scholars and editors and, among the historical insights they offer, shed light on Franklin’s relationship with Yale University. He carried on a decades-long correspondence with Yale President Ezra Stiles on subjects ranging from scientific research to the growing collections of Yale’s library.

John Adams, I guess, would have disagreed with this choice. He said of Dr. Franklin, in a 1783 letter to James Warren: “His whole life has been one continued insult to good manners and to decency.â€

But most of us today are nowhere nearly as censorious of Franklin’s illegitimate son and illegitimate grandson or of Franklin’s (1747) The Speech of Polly Baker, defending a fictional woman for bearing illegitimate children.

Franklin’s accomplishments in literature and scientific experiments and as a founder of the United States are so great that nobody could deny his worthiness as the namesake of a college.

The only problem is that he really had no genuine substantive connection to Yale.

Apparently, what really went on here was was explained in a letter from Salovey:

[A]dopting his name for one of the new colleges, we honor as well the generosity of Charles B. Johnson ’54 B.A., who considers Franklin a personal role model. Mr. Johnson’s contribution to enable the construction of the new colleges is the single largest gift made to Yale. Pauli Murray College and Benjamin Franklin College, which will open Yale’s doors to thousands of additional future students, would not have been possible without his philanthropic vision.

Money talks. It isn’t really appropriate, but the man paid for the piper, so he gets to call the tune. It could be worse. We could have a residential college named “Pforzheimer.”

——————————–

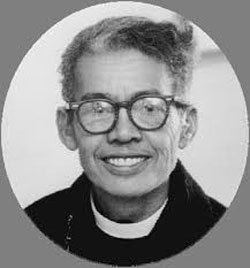

Anna Pauline “Pauli” Murray, Y ’65 J.S.D., ’79 Hon. D.Div., four-fer, maybe five-fer

And, then, of course, we come to the pièce de résistance, the inevitable jolie cadeau de la révolution française, the big, fat chunk of tokenism:

The northern-most college, sited closest to Science Hill, Pauli Murray College will honor a Yale alumna (’65 J.S.D., ’79 Hon. D.Div.) noted for her achievements in law and religion, and for her leadership in civil rights and the advancement of women. Pauli Murray enrolled at Hunter College in the 1920s, graduating in 1933 after deferring her studies following the Great Depression. Later, she began an unsuccessful campaign to enter the all-white University of North Carolina. Murray’s case received national publicity, and she became widely recognized as a civil rights activist.

A graduate of Howard Law School, Murray had an extraordinary legal career as a champion of racial and gender equity. United States Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall cited her book, States’ Laws on Race and Color, for its influence on the lawyers fighting segregation laws. President John F. Kennedy appointed her to the Committee on Civil and Political Rights of the President’s Commission on the Status of Women.

Awarded a fellowship by the Ford Foundation, Murray pursued a doctorate in law at Yale in order to further her scholarly work on gender and racial justice. She co-authored Jane Crow and the Law: Sex Discrimination and Title VII, in which she drew parallels between gender-based discrimination and Jim Crow laws. In 1965, she received her J.S.D. from Yale Law School, the first African-American to do so. Her dissertation was entitled, Roots of the Racial Crisis: Prologue to Policy. Immediately thereafter, she served as counsel in White v. Crook, which successfully challenged discrimination on the basis of sex and race in jury selection. She was a cofounder, with thirty-one others, of the National Organization for Women.

Murray was a vice president of Benedict College in Columbia, South Carolina; she left to become a professor at Brandeis University, where she earned tenure and taught until 1973. She was the first person to teach African-American studies and women’s studies at Brandeis.

The final stage of Murray’s career continued a life marked by confronting challenges and breaking down barriers. At age 63, inspired by her connections with other women in the Episcopal Church, she left Brandeis and enrolled at the General Theological Seminary. She became the first African-American woman ordained as an Episcopal priest..

And you’ve got to hand it to Salovey, the Yale Administration, and the Corporation. When they set out to truckle and to pander to contemporary whiny left-wing identity groups, they do it good and proper. Obviously, in reality, there are no females, there are no African-Americans associated with Yale so eminent or of such accomplishment as to be even close to being genuinely worthy of being the namesake of a Yale College. Hilariously, as well, nobody outside the organized left has ever actually heard of Pauli Murray but, upon looking her up, one finds that, if you are going to pander, she is the cat’s pajamas. Pauli Murray was merely a minor left-wing public nuisance and lived and died in obscurity, but she combines in one small dusky package absolutely everything: she was female, African-American, queer, an Episcopalian priestess, and a transgender wannabee. What a deal! Let’s hope Yale, in future, treats Murray College as its own equivalent of California, and sends all of its commies, fruits, and nuts to go live there at the remote extremity of the campus.