I

Swear by what the sages spoke

Round the Mareotic Lake

That the Witch of Atlas knew,

Spoke and set the cocks a-crow.

Swear by those horsemen, by those women

Complexion and form prove superhuman,

That pale, long-visaged company

That air in immortality

Completeness of their passions won;

Now they ride the wintry dawn

Where Ben Bulben sets the scene.

Here’s the gist of what they mean.

II

Many times man lives and dies

Between his two eternities,

That of race and that of soul,

And ancient Ireland knew it all.

Whether man die in his bed

Or the rifle knocks him dead,

A brief parting from those dear

Is the worst man has to fear.

Though grave-diggers’ toil is long,

Sharp their spades, their muscles strong.

They but thrust their buried men

Back in the human mind again.

III

You that Mitchel’s prayer have heard,

“Send war in our time, O Lord!â€

Know that when all words are said

And a man is fighting mad,

Something drops from eyes long blind,

He completes his partial mind,

For an instant stands at ease,

Laughs aloud, his heart at peace.

Even the wisest man grows tense

With some sort of violence

Before he can accomplish fate,

Know his work or choose his mate.

IV

Poet and sculptor, do the work,

Nor let the modish painter shirk

What his great forefathers did.

Bring the soul of man to God,

Make him fill the cradles right.

Measurement began our might:

Forms a stark Egyptian thought,

Forms that gentler Phidias wrought.

Michael Angelo left a proof

On the Sistine Chapel roof,

Where but half-awakened Adam

Can disturb globe-trotting Madam

Till her bowels are in heat,

Proof that there’s a purpose set

Before the secret working mind:

Profane perfection of mankind.

Quattrocento put in paint

On backgrounds for a God or Saint

Gardens where a soul’s at ease;

Where everything that meets the eye,

Flowers and grass and cloudless sky,

Resemble forms that are or seem

When sleepers wake and yet still dream.

And when it’s vanished still declare,

With only bed and bedstead there,

That heavens had opened.

Gyres run on;

When that greater dream had gone

Calvert and Wilson, Blake and Claude,

Prepared a rest for the people of God,

Palmer’s phrase, but after that

Confusion fell upon our thought.

V

Irish poets, learn your trade,

Sing whatever is well made,

Scorn the sort now growing up

All out of shape from toe to top,

Their unremembering hearts and heads

Base-born products of base beds.

Sing the peasantry, and then

Hard-riding country gentlemen,

The holiness of monks, and after

Porter-drinkers’ randy laughter;

Sing the lords and ladies gay

That were beaten into the clay

Through seven heroic centuries;

Cast your mind on other days

That we in coming days may be

Still the indomitable Irishry.

VI

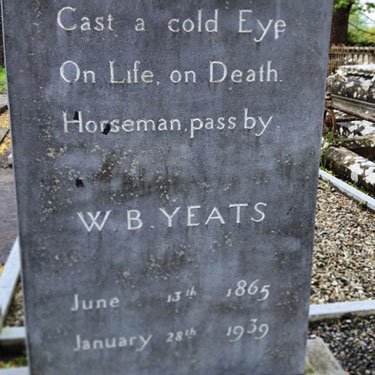

Under bare Ben Bulben’s head

In Drumcliff churchyard Yeats is laid.

An ancestor was rector there

Long years ago, a church stands near,

By the road an ancient cross.

No marble, no conventional phrase;

On limestone quarried near the spot

By his command these words are cut:

Cast a cold eye

On life, on death.