Category Archive 'Ross Douthat'

17 Jan 2025

Marc Andreessen, in a NYT interview with Ross Douthat explains why a significant segment of Silicon Valley recently changed sides politically.

I think the Valley before me, from the ’50s through the ’70s, was normie Republicans. They were businesspeople, C.E.O.s, investors, and they would have been, I assume at the time, big fans of Nixon, big fans of Reagan. That era was basically over by the time I arrived. I met a few of those guys, but when I got there in ’94, it was in the full swing of Clinton-Gore, the restoration of the Democratic Party and recovery of liberalism as a mainstream political force. …

Normie Democrat is what I call the Deal, with a capital D. Nobody ever wrote this down; it was just something everybody understood: You’re me, you show up, you’re an entrepreneur, you’re a capitalist, you start a company, you grow a company, and if it works, you make a lot of money. And then the company itself is good because it’s bringing new technology to the world that makes the world a better place, but then you make a lot of money, and you give the money away. Through that, you absolve yourself of all of your sins.

Then in your obituary, it talks about what an incredible person you were, both in your business career and in your philanthropic career. And by the way, you’re a Democrat, you’re pro–gay rights, you’re pro-abortion, you’re pro all the fashionable and appropriate social causes of the time. There are no trade-offs. This is the Deal.

Then, of course, everybody knows Republicans are just knuckle-dragging racists. It was taken as given that there was going to be this great relationship. And of course, it worked so well for the Democratic Party. Clinton and Gore sailed to a re-election in ’96. And the Valley was locked in for 100 years to come to be straight-up conventional blue Democrat. …

Trump was a new arrival in ’15, and then basically lots of changes followed. But what I experienced was the changes started in 2012, 2013, 2014 and were snowballing hard, at least in the Valley, at least among kids. And I think, to some extent, Trump was actually a reaction to those changes.

Douthat: Those changes you’re talking about, are they fundamentally about policies being made by the Obama White House, or are they fundamentally about the big shift leftward among young people that clearly started in that era?

Andreessen: So I would say both, and the unifying thread here is, I believe it’s the children of the elites. The most privileged people in society, the most successful, send their kids to the most politically radical institutions, which teach them how to be America-hating communists.

They fan out into the professions, and our companies hire a lot of kids out of the top universities, of course. And then, by the way, a lot of them go into government, and so we’re not only talking about a wave of new arrivals into the tech companies.

We’re also talking about a wave of new arrivals into the congressional offices. And of course, they all know each other, and so all of a sudden you have this influx, this new cohort.

And my only conclusion is what changed was basically the kids. In other words, the young children of the privileged going to the top universities between 2008 to 2012, they basically radicalized hard at the universities, I think, primarily as a consequence of the global financial crisis and probably Iraq. Throw that in there also. But for whatever reason, they radicalized hard. Read the rest of this entry »

06 Dec 2018

White Anglo-Saxon members of a certain society at Yale.

Ross Douthat comments intelligently on just how much the passing of George H.W. Bush makes Americans regret that times have changed and the Old American Establishment that George Bush was a part of no longer rules America. Its “diverse” and meritocratic replacement possesses neither the same kind of class nor the same legitimacy.

The nostalgia flowing since the passing of George H.W. Bush has many wellsprings: admiration for the World War II generation and its dying breed of warrior-politicians, the usual belated media affection for moderate Republicans, the contrast between the elder Bush’s foreign policy successes and the failures of his son, and the contrast between any honorable politician and the current occupant of the Oval Office.

But two of the more critical takes on Bush nostalgia got closer to the heart of what was being mourned, in distant hindsight, with his death. Writing in The Atlantic, Peter Beinart described the elder Bush as the last president deemed “legitimate†by both of our country’s warring tribes — before the age of presidential sex scandals, plurality-winning and popular-vote-losing chief executives, and white resentment of the first black president. Also in The Atlantic, Franklin Foer described “the subtext†of Bush nostalgia as a “fondness for a bygone institution known as the Establishment, hardened in the cold of New England boarding schools, acculturated by the late-night rituals of Skull and Bones, sent off to the world with a sense of noblesse oblige. For more than a century, this Establishment resided at the top of the American caste system. Now it is gone, and apparently people wish it weren’t.â€

I think you can usefully combine these takes, and describe Bush nostalgia as a longing for something America used to have and doesn’t really any more — a ruling class that was widely (not universally, but more widely than today) deemed legitimate, and that inspired various kinds of trust (intergenerational, institutional) conspicuously absent in our society today.

Put simply, Americans miss Bush because we miss the WASPs — because we feel, at some level, that their more meritocratic and diverse and secular successors rule us neither as wisely nor as well. …

However, one of the lessons of the age of meritocracy is that building a more democratic and inclusive ruling class is harder than it looks, and even perhaps a contradiction in terms. You can get rid of the social registers and let women into your secret societies and privilege SATs over recommendations from the rector of Justin and the headmaster of Saint Grottlesex … and you still end up with something that is clearly a self-replicating upper class, a powerful elite, filling your schools and running your public institutions.

Not only that, but you even end up with an elite that literally uses the same strategy of exclusion that WASPs once used against Jews to preserve its particular definition of diversity from high-achieving Asians — with the only difference being that our elite is more determined to deceive itself about how and why it’s discriminating.

So if some of the elder Bush’s mourners wish we still had a WASP establishment, their desire probably reflects a belated realization that certain of the old establishment’s vices were inherent to any elite, that meritocracy creates its own forms of exclusion — and that the WASPs had virtues that their successors have failed to inherit or revive.

Those virtues included a spirit of noblesse oblige and personal austerity and piety that went beyond the thank-you notes and boat shoes and prep school chapel going — a spirit that trained the most privileged children for service, not just success, that sent men like Bush into combat alongside the sons of farmers and mechanics in the same way that it sent missionaries and diplomats abroad in the service of their churches and their country.

The WASP virtues also included a cosmopolitanism that was often more authentic than our own performative variety — a cosmopolitanism that coexisted with white man’s burden racism but also sometimes transcended it, because for every Brahmin bigot there was an Arabist or China hand or Hispanophile who understood the non-American world better than some of today’s shallow multiculturalists.

And somehow the combination of pious obligation joined to cosmopolitanism gave the old establishment a distinctive competence and effectiveness in statesmanship — one that from the late-19th century through the middle of the 1960s was arguably unmatched among the various imperial elites with whom our establishment contended, and that certainly hasn’t been matched by our feckless leaders in the years since George H.W. Bush went down to political defeat.

So as an American in the old dispensation, you didn’t have to like the establishment — and certainly its members were often eminently hateable — to prefer their leadership to many of the possible alternatives. And as an American today, you don’t have to miss everything about the WASPs, or particularly like their remaining heirs, to feel nostalgic for their competence.

RTWT

17 Nov 2018

The dining hall of my personal Hogwarts.

Ross Douthat explained last year why the Harry Potter books struck such a chord in our contemporary meritocratic world.

[I]f you take the Potterverse seriously as an allegory for ours, the most noteworthy divide isn’t between the good multicultural wizards and the bad racist ones. It’s between all the wizards, good and bad, and everybody else — the Muggles.

For the six readers who have never read the Potter books but who have stuck with the column thus far nonetheless: Muggles are non-magical folks, the billions of regular everyday human beings who live and work in blissful ignorance that the wizarding world exists. The only exception comes when one of them marries a wizard or has the genetic luck to give birth to a magic-capable child, in which case they get to watch their offspring ascend to one of the wizarding academies while they experience its raptures and revelations secondhand.

The proper treatment of Muggles, meanwhile, is the great controversy within the wizarding world, where the good guys want them protected, left alone and sometimes studied, while the bad guys want to see them subjugated or enslaved (and all the Muggle-born “mudbloods†purged from the wizarding ranks).

All of this plays as an allegory for racism, up to a point … but only up to a point, because what’s notable is that nobody actually wants to see the mass of Muggles (as opposed to their occasional wizardish offspring) integrated into the wizarding society. Indeed, according to the rules of Rowling’s universe, that seems to be impossible. You’re either born with magic or you aren’t, and if you aren’t there’s really not any obvious place for you in Hogwarts or any other wizarding establishment.

So even from the perspective of the enlightened, progressive wizarding faction, then, Muggles are basically just a vast surplus population that occasionally produces the new blood that wizarding needs to avoid becoming just a society of snobbish old-money inbred Draco Malfoys. And if that were to change, if any old Muggle could suddenly be trained in magic, the whole thrill of Harry Potter’s acceptance at Hogwarts would lose its narrative frisson, its admission-to-the-inner-circle thrill.

Which makes the thrill of becoming a magical initiate in the Potterverse remarkably similar to the thrill of being chosen by the modern meritocracy, plucked from the ordinary ranks of life and ushered into gothic halls and exclusive classrooms, where you will be sorted — though not by a magic hat, admittedly — according to your talents and your just deserts.

I am stealing this magic-and-meritocracy parallel from the pseudonymous blogger Spotted Toad, who wrote a fine post discussing how much the Potter novels and movies trade upon the powerful loyalty that their readers feel, or feel that they should feel, toward their teachers and their schools. But not just any school — not some suburban John Hughes-style high school or generic Podunk U. No, it’s loyalty to a selective school, with an antique pedigree but a modern claim to excellence, an exclusive admissions process but a pleasingly multicultural student body. A school where everybody knows that they belong, because they can do the necessary magic and ordinary Muggles can’t.

Thus the Potterverse, as Toad writes, is about “the legitimacy of authority that comes from schools†— Ivy League schools, elite schools, U.S. News & World Report top 100 schools. And because “contemporary liberalism is the ideology of imperial academia, funneled through media and nonprofits and governmental agencies but responsible ultimately only to itself,†a story about a wizarding academy is the perfect fantasy story for the liberal meritocracy to tell about itself. …

In the Potter novels the selective school is conterminous with wizarding society as a whole (allowing for some elves and goblins to do maintenance and keep the books), and thus the threats to that world’s liberal integrity all come from within the academy’s walls, from Slytherin House and its arrogant aristocrats, who must be constantly confronted in the halls and classrooms of the beloved school itself. Voldemort, the dark lord, has Muggle blood, but he isn’t trying to rally an army of non-magic-wielders to seize Hogwarts’ towers; he’s trying to remake meritocratic — er, magical — institutions in his own dark image. And so the battle for Harvard — er, Hogwarts — is the battle for the world.

Which is basically the premise of a great deal of youthful liberal activism these days — that once the last remnants of Slytherin are eradicated from the leafy quads of Yale or Middlebury, once Draco Malfoy’s frat or final club is closed and the last Death-Eater sympathizers purged from the faculty, then the battle of ideas will have been finally and fully won.

But what house was Boris Johnson in?

RTWT

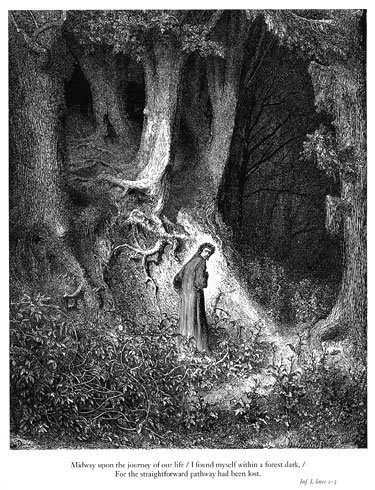

27 Oct 2016

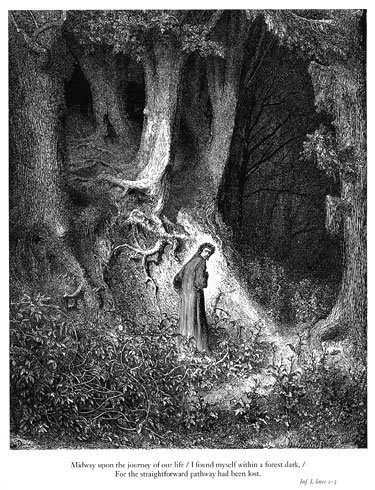

Gustave Dore: Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita/ mi ritrovai per una selva oscura,/ ché la diritta via era smarrita.

Ross Douthat, an echt conservative intellectual, argues that conservative intellectuals should blame themselves for the Trumpkin peasant revolt. Firstly, by allying with George W. Bush’s failed presidency, and secondly, by relying on AM Talk Radio (Sean Hannity) and Internet bloggers (Matt Drudge, Breitbart) to do so much of the message communicating.

Every political movement in a democracy is shaped like a pyramid — elite actors on the top, the masses underneath. But the pyramid that is modern American conservatism has always been misshapen, with a wide, squat base that tapers far too quickly at its peak.

The broad base is right-wing populism, in all its post-World War II varietals: Orange County Cold Warriors, “Silent Majority†hard hats, Southern evangelicals, Reagan Democrats, the Tea Party, the Trumpistas. The too-small peak is the right’s intellectual cadres, its philosophers and legal theorists and foreign policy hands and wonks.

The peak is small because conservatives have always had a relatively weak presence within what James Burnham, one of modern conservatism’s intellectual godfathers, called the “managerial class†— the largely liberal meritocrats who staff our legal establishment, our bureaucracy, our culture industries, our universities. Whether as provincial critics of this class or dissidents within it, conservative intellectuals have long depended on populism to win the power that the managerial elite’s liberal tilt would otherwise deny them. …

But now, in the age of Donald Trump, the populists have seemingly decided that they can get along just fine without any elite direction whatsoever. …

History does not stand still; crises do not last forever. Eventually a path for conservative intellectuals will open.

But for now we find ourselves in a dark wood, with the straight way lost.

25 Apr 2016

Nicolás Gómez Dávila: “The reactionary today is merely a traveler who suffers shipwreck with dignity.”

The New York Times tame house-conservative Ross Douthat finds himself yearning these days, as the gods of establishment Progressivism and Conservatism seem to be failing, for a higher-proof version of right-wing inspiration. Of course, being Ross Douthat, he is careful to stipulate that the Reactionary philosophy he yearns for should be violative of left-wing shibboleths but, please! not too transgressive.

[W]hile reactionary thought is prone to real wickedness, it also contains real insights. … Reactionary assumptions about human nature — the intractability of tribe and culture, the fragility of order, the evils that come in with capital-P Progress, the inevitable return of hierarchy, the ease of intellectual and aesthetic decline, the poverty of modern substitutes for family and patria and religion — are not always vindicated. But sometimes? Yes, sometimes. Often? Maybe even often.

Both liberalism and conservatism can incorporate some of these insights. But both have an optimism that blinds them to inconvenient truths. The liberal sees that conservatives were foolish to imagine Iraq remade as a democracy; the conservative sees that liberals were foolish to imagine Europe remade as a post-national utopia with its borders open to the Muslim world. But only the reactionary sees both.

Is there a way to make room for the reactionary mind in our intellectual life, though, without making room for racialist obsessions and fantasies of enlightened despotism? So far the evidence from neoreaction is not exactly encouraging.

Yet its strange viral appeal is also evidence that ideas can’t be permanently repressed when something in them still seems true.

Maybe one answer is to avoid systemization, to welcome a reactionary style that’s artistic, aphoristic and religious, while rejecting the idea of a reactionary blueprint for our politics. From Eliot and Waugh and Kipling to Michel Houellebecq, there’s a reactionary canon waiting to be celebrated as such, rather than just read through a lens of grudging aesthetic respect but ideological disapproval.

A phrase from the right-wing Colombian philosopher Nicolás Gómez Dávila could serve as such a movement’s mission statement. His goal, he wrote, was not a comprehensive political schema but a “reactionary patchwork.†Which might be the best way for reaction to become something genuinely new: to offer itself, not as ideological rival to liberalism and conservatism, but as a vision as strange and motley as reality itself.

By “reactionary,” of course, Ross Douthat is referring to beyond-the-pale forms of anti-Progressive, anti-Liberal political thought which reject such core principles of democratic modernism as Democracy, Pacifism, Internationalism, and Egalitarianism.

15 Nov 2015

“March of Resilience” at Yale

Ross Douthat obviously does not agree with the crybullying of today’s radicalized college students, but he recognizes that it was the same academic establishment they are insulting and revolting against which made the corrupt bargain with the revolutionary left that is responsible for the presence of the toxins within the national educational system which produced the current infatuated mobs howling at their doors. There are the crazed students, heads full of Marxist agitprop, filled with passionate intensity confronting the empty-headed and empty-hearted liberals who never believed there could be such a thing as an enemy to the left.

The protesters at Yale and Missouri and a longer list of schools stand accused of being spoiled, silly, self-dramatizing — and many of them are. But they’re also dealing with a university system that’s genuinely corrupt, and that’s long relied on rote appeals to the activists’ own left-wing pieties to cloak its utter lack of higher purpose.

And within this system, the contemporary college student is actually a strange blend of the pampered and the exploited.

This is true of the college football recruit who’s a god on campus but also an unpaid cog in a lucrative football franchise that has a public college vestigially attached.

It’s true of the liberal arts student who’s saddled with absurd debts to pay for an education that doesn’t even try to pass along any version of Matthew Arnold’s “ best which has been thought and said,†and often just induces mental breakdowns in the pursuit of worldly success.

It’s true of the working class or minority student who’s expected to lend a patina of diversity to a campus organized to deliver good times to rich kids whose parents pay full freight. And then it’s true of the rich girl who discovers the same university that promised her a carefree Rumspringa (justified on high feminist principle, of course) doesn’t want to hear a word about what happened to her at that frat party over the weekend.

The protesters may be obnoxious enemies of free debate, in other words, but they aren’t wrong to smell the rot around them. And they’re vindicated every time they push and an administrator caves: It’s proof that they have a monopoly on moral spine, and that any small-l liberal alternative is simply hollow.

Or as the great Walter Sobchak might have put it: “Say what you want about the tenets of political correctness, Dude, at least it’s an ethos.â€

Which might turn out to be the only epitaph for the modern university anybody needs to write.

23 Apr 2012

One major modern heresiarch

Ross Douthat, in an argument with William Saletan, makes the point that Liberalism, aka Leftism, is merely the same Christianity we are all familiar with, modified into a materialist heresy with the scientific state at the center of the cosmos instead of Jehovah, no afterlife, and all the traditional teachings regarding celibacy and sex reversed.

[W]hen I look at your secular liberalism, I see a system of thought that looks rather like a Christian heresy, and not necessarily a particularly coherent one at that. In [his recent book] Bad Religion , I describe heresy as a form of belief that tends to emphasize certain elements of the Christian synthesis while downgrading or dismissing other aspects of that whole. And it isn’t surprising that liberalism, which after all developed in a Christian civilization, does exactly that, drawing implicitly on the Christian intellectual inheritance to ground its liberty-equality-fraternity ideals. , I describe heresy as a form of belief that tends to emphasize certain elements of the Christian synthesis while downgrading or dismissing other aspects of that whole. And it isn’t surprising that liberalism, which after all developed in a Christian civilization, does exactly that, drawing implicitly on the Christian intellectual inheritance to ground its liberty-equality-fraternity ideals.

Indeed, it’s completely obvious that absent the Christian faith, there would be no liberalism at all. No ideal of universal human rights without Jesus’ radical upending of social hierarchies (including his death alongside common criminals on the cross). No separation of church and state without the gospels’ “render unto Caesar†and St. Augustine’s two cities. No liberal confidence about the march of historical progress without the Judeo-Christian interpretation of history as an unfolding story rather than an endlessly repeating wheel.

And what’s more, to me, contemporary liberals’ obsession with the supposed backwardness of Christian sexual ethics—an obsession that far outstrips sex’s actual role in the preaching and practice of Christian faith—reflects a subconscious liberal knowledge that Christianity is their theological mother, and they’re its half-rebellious child. You can see in it the child’s characteristic desire to finally overthrow the last bastion of parental authority, joined to a continued desire for the parent’s approval for their choices and beliefs. …

[T]he more purely secular liberalism has become, the more it has spent down its Christian inheritance—the more its ideals seem to hang from what Christopher Hitchens’ Calvinist sparring partner Douglas Wilson has called intellectual “skyhooks,†suspended halfway between our earth and the heaven on which many liberals have long since given up. Say what you will about the prosperity gospel and the cult of the God Within and the other theologies I criticize in Bad Religion, but at least they have a metaphysically coherent picture of the universe to justify their claims. Whereas much of today’s liberalism expects me to respect its moral fervor even as it denies the revelation that once justified that fervor in the first place. It insists that it is a purely secular and scientific enterprise even as it grounds its politics in metaphysical claims. (You will not find the principle of absolute human equality in evolutionary theory, or universal human rights anywhere in physics.) It complains that Christian teachings on homosexuality do violence to gay people’s equal dignity—but if the world is just matter in motion, whence comes this dignity? What justifies and sustains it? Why should I grant it such intense, almost supernatural respect?

He’s perfectly right. What is modern environmentalism, after all, other than a particularly infuriating recrudescence of Dualism?

07 Nov 2011

Helmuth Karl Bernhard Graf von Moltke (1800-1891)

Ross Douthat, I think, rather laboriously reaches the same conclusion Count von Moltke reached long ago, but Douthat miscategorizes the offenders.

In hereditary aristocracies, debacles tend to flow from stupidity and pigheadedness: think of the Charge of the Light Brigade or the Battle of the Somme. In one-party states, they tend to flow from ideological mania: think of China’s Great Leap Forward, or Stalin’s experiment with Lysenkoist agriculture.

In meritocracies, though, it’s the very intelligence of our leaders that creates the worst disasters. Convinced that their own skills are equal to any task or challenge, meritocrats take risks than lower-wattage elites would never even contemplate, embark on more hubristic projects, and become infatuated with statistical models that hold out the promise of a perfectly rational and frictionless world. (Or as Calvin Trillin put it in these pages, quoting a tweedy WASP waxing nostalgic for the days when Wall Street was dominated by his fellow bluebloods: –Do you think our guys could have invented, say, credit default swaps? Give me a break! They couldn’t have done the math.–)

Field Marshall von Moltke conceptually divided his officers into a four part matrix:

— Smart & Lazy: I make them my Commanders because they make the right thing happen but find the easiest way to accomplish the mission.

— Smart & Energetic: I make them my General Staff Officers because they make intelligent plans that make the right things happen.

— Dumb & Lazy: There are menial tasks that require an officer to perform that they can accomplish and they follow orders without causing much harm

— Dumb & Energetic: These are dangerous and must be eliminated. They cause thing to happen but the wrong things so cause trouble.

In which category, do Ross Douthat’s meritocrats really belong? It seems obvious to me.

Douthat has the precise same problem our contemporary “meritocracy” has: mistaking credentials and narrowly focused technical expertise for intelligence. In reality, the meritocratic system of education rewards energy and proficiency in areas requiring certain kinds of intellectual ability almost entirely divorced from wisdom, integrity, and good judgment. What our system of education characteristically produces are skilled sophists and opportunists, most conspicuously ingenious in conformity. It is a system designed to promote the energetic but stupid.

20 May 2010

Ross Douthat wonders aloud if any political movement, any reaction on the part of the electorate, can possibly overcome the one directional dynamic of Progressive Statism.

This feels like a populist moment. Americans are Tea Partying. Greeks are rioting. Incumbents are being thrown out; the Federal Reserve is facing an audit; Goldman Sachs is facing prosecution. In Kentucky, Ron Paul’s son might be about to win a Republican Senate primary.

But look through these anti-establishment theatrics to the deep structures of political and economic power, and suddenly the surge of populism feels like so much sound and fury, obscuring the real story of our time. From Washington to Athens, the economic crisis is producing consolidation rather than revolution, the entrenchment of authority rather than its diffusion, and the concentration of power in the hands of the same elite that presided over the disasters in the first place. …

Taken case by case, many of these policy choices are perfectly defensible. Taken as a whole, they suggest a system that only knows how to move in one direction. If consolidation creates a crisis, the answer is further consolidation. If economic centralization has unintended consequences, then you need political centralization to clean up the mess. If a government conspicuously fails to prevent a terrorist attack or a real estate bubble, then obviously it needs to be given more powers to prevent the next one, or the one after that.

The C.I.A. and F.B.I. didn’t stop 9/11, so now we have the Department of Homeland Security. Decades of government subsidies for homebuyers helped create the housing crash, so now the government is subsidizing the auto industry, the green-energy industry, the health care sector …

The pattern applies to personnel as well as policy. If Robert Rubin’s mistakes helped create an out-of-control financial sector, then naturally you need Timothy Geithner and Lawrence Summers — Rubin’s protégés — to set things right. After all, who else are you going to trust with all that consolidated power? Ron Paul? Dennis Kucinich? Sarah Palin?

This is the perverse logic of meritocracy. Once a system grows sufficiently complex, it doesn’t matter how badly our best and brightest foul things up. Every crisis increases their authority, because they seem to be the only ones who understand the system well enough to fix it.

But their fixes tend to make the system even more complex and centralized, and more vulnerable to the next national-security surprise, the next natural disaster, the next economic crisis. Which is why, despite all the populist backlash and all the promises from Washington, this isn’t the end of the “too big to fail†era. It’s the beginning.

10 Aug 2008

Ross Douthat, in the Atlantic, is less than sympathetic.

You stay classy, John Edwards:

Edwards made a point of telling Woodruff that his wife’s cancer was in remission when he began the affair with Hunter. Elizabeth Edwards has since been diagnosed with an incurable form of the disease.

Also, he made a point of telling Woodruff that he remained the son of a mill worker throughout the entire affair.

It looks like they won’t have Flem Snopes to kick around anymore.

——————————–

Hat tip to Frank Dobbs.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Ross Douthat' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|