Category Archive 'Susan Sontag'

18 May 2019

Lauren Elkin, in Aeon, pays tribute to the late Susan Sontag’s “monstrous” appetites for thinking, culture and the arts, and living la vie de la Bohême.”

There are things it has taken me two decades as a serious reader and writer to become aware of or to articulate, things that Sontag noticed straight off the bat in Against Interpretation, at the age of 33. Skimming her essays today, I’m struck by the sharpness of their insights and the breadth of their references. Dismayingly, nearly 20 years after I first read her, I still have not caught up to Sontag, and neither has our critical culture.

You won’t find Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche, Hume or György Lukács nonchalantly dotting the page in criticism today; it is supposed that readers aren’t up for it. But Sontag charges in and dares to distinguish between their good and mediocre work. She isn’t afraid of Jean-Paul Sartre. Writing on his book on Jean Genet, she notes: ‘In Genet, Sartre has found his ideal subject. To be sure, he has drowned in him.’ She stood up to men held up as moral giants. Albert Camus, George Orwell, James Baldwin? Excellent essayists, but overrated as novelists. In 1966, Sontag checked an America that was in thrall to realism and normative morality, demonstrating how to respond to the ‘seers, spiritual adventurers, and social pariahs’ as she put it in her essay on the French dramatist Antonin Artaud.

Her special brand of monstrous relentlessness saw her go in search of paradox. Moderation, and those who practised it, never interested her. It seemed to her like a cop-out. And she believed that only the immoderate rose to the level of the culture-hero: people who took things to extremes, who were ‘repetitive, obsessive, and impolite, who impress by force’, as she wrote of the French philosopher Simone Weil. Sane writers are the least interesting writers, and Sontag had that stripe of insanity, like that grey thatch of hair, that made you sit up and listen, and also made you a little nervous. Her pungent public personality won her a reputation for being, as Sigrid Nunez put it in 2011, ‘a monster of arrogance and inconsideration’. She was a monster – for art. She read everything, watched everything, listened to everything, went to see everything. How did she fit it all in? It’s as if she lived several lives in one. She sat in the middle of the third row at the cinema, so that the image would overwhelm her. She would not, could not, relax. Art was too important. Life was too important.

Look across her many books: she simply does not let up. Every sentence is a new challenge; there is no filler. I’ve lost track of how many times I’ve read On Photography (1977), and every time it’s like I’m reading a new book. There’s something very constructed and Germanic about her sentences; I find myself reading her cubistly, not left to right only but also up and down, piecing together what she’s saying chunk by chunk instead of line by line. She quotes very infrequently, and is less interested in local textual moments than in building up a global reading of an author’s work. She frequently revised her opinions, so no sooner have I got a handle on On Photography than she’s off on another tack in Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), further refining it in ‘Photography: a Little Summa’ (2003). She was uninterested in boiling down her views to an easily citable argument; she resisted simplification in every aspect of her life and work.

‘Boring, like servile, was one of her favourite words,’ writes Nunez in Sempre Susan (2011), recalling her time as Sontag’s assistant and her son David’s girlfriend. ‘Another was exemplary. Also, serious.’ The word ‘serious’ and its variants (‘seriousness’, ‘seriously’) appear 120 times in Against Interpretation, a text of 322 pages. That’s every 2.6 pages. For Sontag, seriousness was an all-encompassing, even physical way of being in the world. ‘Yet so far as we love seriousness, as well as life, we are moved by it, nourished by it,’ she wrote in her essay on Weil. ‘In the respect we pay to such lives, we acknowledge the presence of mystery in the world – and mystery is just what the secure possession of the truth, an objective truth, denies.’ Mystery is missing from all that is sage, appropriate, nice, fitting, obedient. Notice Sontag’s emotive, personal choice of words: we are moved by seriousness; it affects her (and, she presumes, her reader) on a primary, physical level.

This is what her detractors so often miss in her work. ‘Mind as Passion’ she called her essay on Canetti. Style. Will. Mind. Passion. These are also words that recur throughout her work. She wasn’t just serious: she was passionate about the mind and its possibilities. The mind, to Sontag, was a feeling organ.

RTWT

I read Against Interpretation during high school, in the 1960s, back in my provincial Pennsylvania small town where films by Bresson and Godard were never shown.

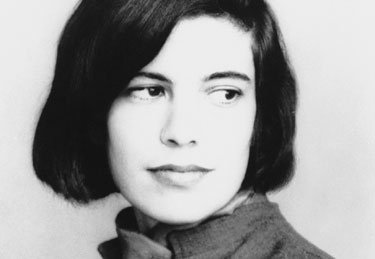

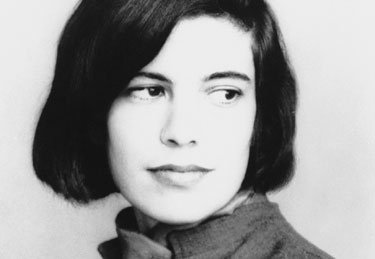

I was already very much on the opposite side of the Culture Wars, but Sontag’s brilliant, deep readings of the cutting edge products and doings of the opposite camp made for fascinating reading. I could not resist falling in love with her intelligence and passionate engagement. I actually traced the cover photo (above) in pencil, and produced a drawing of Sontag of my own and hung it on my wall.

I met her, by accident, years later, and we talked at length, and thereby actually became friendly regular acquaintances. I ran into her frequently at major cultural events in New York in the late 1970s and early ’80s. We always saluted each other, and we sometimes sat together and exchanged comments during a performance. I saw several films in her company at the Bleeker Street Cinema, having run into her by accident. Karen and I sat with her and Lillian Gish during the NYC premiere of the restored print of Abel Gance’s Napoleon (1927), and a merry time was had by all. During the intermission, Sontag introduced us to Steven Spielberg and Gary Lucas with whom she was seeing Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s Parsifal (1982) at Lincoln Center.

She was certainly the greatest critic of contemporary arts and culture generally of her time. Despite her limitless ambition, she was clearly much less successful as a novelist and director. Her taste and capacity to distinguish and appreciate excellence in the work of others was unsurpassed, but she could not do everything at the same level of excellence. Who can?

I would say that her opinions, life, and work were somewhat adversely affected by the inevitable influence upon a passionate young girl of her ethnicity and background of the culture of her time. But, then, as I’ve previously noted, I am myself a perennial critic and opponent of precisely that culture.

Nonethless, despite her born membership of the Left and her admiration for, and association with, the subculture of Perversity, I still liked and admired her personally. And I do still read her with pleasure.

She was guilty of a couple of very unfortunate political statements and, like all the rest of the community of fashion, she was wrong on Vietnam and wrong on pretty much everything politically, but still, in the early ’80s, she condemned a number of Communist atrocities and seemed teetering, for a while, on the edge of breaking with the Left. I won’t tell you the whole story now, but I know that it could have happened.

19 Jun 2018

The young rebellious Sontag.

Nicholas Frankovich notes that youthful rebellion against stodgy, inhibiting norms and standards is great fun, until you find the fences are all down, the norms and standards have disappeared, in politics as in the arts.

Susan Sontag established herself as a public intellectual through original and incisive essays in which she exalted avant-garde over high culture in the 1960s. Late in her career, in the 1990s, she began to have second thoughts. “It never occurred to me that all the stuff I had cherished, and all the people I had cared about in my university education, could be dethroned,†she explained to Joan Acocella of The New Yorker. She had assumed that “all that would happen is that you would set up an annex — you know, a playhouse — in which you could study these naughty new people, who challenged things.â€

The “naughty new people†were mid-20th-century artists, particularly American and European writers and filmmakers, who defied existing conventions of the novel and of narrative in general. In your creation or experience of art, try for a moment to stop asking what it “means,†Sontag advised. Relish the “sensuous surface of art without mucking about in it.†The aesthetic she was celebrating — it amounted to an elevation of form over content — was supposed to be exemplified by the “nouveau roman,†in which plot, character development, and all the empty promises of linear thought were minimized or, better, absent. “What is important now is to recover our senses,†she wrote. “We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more.â€

Alas, what had appealed to Sontag about that kind of formalism “was mostly just the idea of it,†Acocella observed. “I thought I liked William Burroughs and Nathalie Sarraute and Robbe-Grillet,†Sontag told her, “but I didn’t. I actually didn’t.†And now she had regrets. “Little did I know that the avant-garde transgressiveness of the sixties was to become absolutely institutionalized and that most of the gods of high culture would be dethroned and mocked.†In “Thirty Years Later†(1996), Sontag, reflecting on what she had failed to foresee when she wrote the cultural criticism collected in her book Against Interpretation (1966), recounted that she hadn’t yet grasped that

seriousness itself was in the early stages of losing credibility in the culture at large, and that some of the more transgressive art I was enjoying would reinforce frivolous, merely consumerist transgressions. Thirty years later, the undermining of standards of seriousness is almost complete, with the ascendancy of a culture whose most intelligible, persuasive values are drawn from the entertainment industries. Now the very idea of the serious (and the honorable) seems quaint, “unrealistic,†to most people.

…

The difference between the American and the European use of the term “liberal†is often remarked. The former refers, on the whole, to the Left; the latter, to classical liberalism, which until yesterday was the political philosophy — free markets, limited government, individual liberty — of the mainstream American Right. The current populist revolt on the right has flushed to the surface a fact I had underestimated: that when Americans who call themselves conservative say “Down with liberalism,†classical liberalism is a large part of what many of them have in their sights.

Christian anti-liberalism — Alasdair MacIntyre, John Milbank, David L. Schindler, the Communio school — enchanted me somewhat until classical liberalism in the flesh began to manifest increasing vulnerability. It has to fend off enemies on two fronts now, the right as well as the left. Like Susan Sontag lamenting over the rapid dumbing down of American culture in the late 20th century, I see my mood has changed. What had appealed to me about MacIntyre, Milbank, and the whole crew of “naughty new people who challenged things†was not the possibility that their pictures and diagrams of anti-liberalism would ever escape from the page and the screen and result in political consequences. The idea of anti-liberalism, that’s all, is what I fancied. The realization of it, or the attempt to realize it, turns out to be messy, even ugly, and it appears to be tending toward the ever messier and uglier.

RTWT

03 Aug 2015

A recently much-praised article by Helen Andrews, in the Summer issue of University Bookman, designates Left Coast lesbian literateur Terry Castle as “the Anti-[Camille]-Paglia.” I was not familiar with La Castle, but a link in the essay led me to this affectionate (and irritated) posthumous tribute to a mutual friend: the late Susan Sontag.

Enfin – la fin. I heard she was dead as Bev and I were driving back from my mother’s after Christmas. Blakey called on the cellphone from Chicago to say she had just read about it online; it would be on the front page of the New York Times the next day. It was, but news of the Asian tsunami crowded it out. (The catty thing to say here would be that Sontag would have been annoyed at being upstaged; the honest thing to say is that she wouldn’t have been.) The Times did another piece a few days later – a somewhat dreary set of passages from her books, entitled: ‘No Hard Books, or Easy Deaths’. (An odd title: her death wasn’t easy, but she was all about hard books.) And in the weeks since, the New Yorker, New York Review of Books and various other highbrow mags have kicked in with the predictable tributes.

But I’ve had the feeling the real reckoning has yet to begin. The reaction, to my mind, has been a bit perfunctory and stilted. A good part of her characteristic ‘effect’ – what one might call her novelistic charm – has not yet been put into words. Among other things, Sontag was a great comic character: Dickens or Flaubert or James would have had a field day with her. The carefully cultivated moral seriousness – strenuousness might be a better word – co-existed with a fantastical, Mrs Jellyby-like absurdity. Sontag’s complicated and charismatic sexuality was part of this comic side of her life. The high-mindedness, the high-handedness, commingled with a love of gossip, drollery and seductive acting out – and, when she was in a benign and unthreatened mood, a fair amount of ironic self-knowledge. …

At the moment it’s hard to imagine anyone ever possessing the same symbolic weight, the same adamantine hardness, or having the same casual imperial hold over such a large chunk of my brain. I am starting to think in any case that she was part of a certain neural development that, purely physiologically speaking, can never be repeated. All those years ago one evolved a hallucination about what mental life could be and she was it. She’s still in there, enfolded somehow in the deepest layers of the grey matter. Yes: Susan Sontag was sibylline and hokey and often a great bore. She was a troubled and brilliant American. …

Being not a lesbian and of a generation younger than herself, my own relationship with Susan Sontag was both slighter and less vexed.

Sontag was rather an adolescent intellectual idol of mine. Her early critical essays (of the Against Interpretation period) delivered to the provincial reader like myself up-to-the-minute reports (for good or ill) of life at the Parisian and Manhattan cutting edges of contemporary culture.

I was, from my teenage years, an opponent of Modernism and Leftism, and Sontag was the head cheerleader of both. I usually despised the entire worldview and being of representatives of the establishment pseudo-intelligentsia. I typically read the Times Book Review and Arts Section and the New Yorker with a bitter sneer curling my lip. But Sontag was a different case. She was on the wrong side, but she was obviously a genuine, and absolutely brilliant, intellectual.

I’d always had a hankering to meet Susan Sontag, and finally by one of the most preposterous of circumstances I did. Karen and I were back in Pennsylvania one weekend fishing my major boyhood trout stream, Fishing Creek in Columbia County. As we drove through Bloomsburg, we found posted everywhere announcements of a film screening and lecture at Bloomsburg State U. (not much earlier: Bloomsburg State Teachers’ College) by Susan Sontag herself.

Sontag was a bit startled when an adult couple, reeking of sunscreen and insect repellent and fresh out of waders, arrived to join the throng of English professors and admiring undergraduates. We immediately secured her attention, introduced ourselves, and rather monopolized the event by interviewing Sontag ourselves. We naturally inquired how it came to be that an internationally-renowned cultural demi-goddess could be found speaking at, er.. ahem…, one of the less illustrious institutions of higher education rather than atop Olympus, and Sontag grinned ruefully and explained that she paid her basic living expenses by doing twelve (outrageously highly-paid) appearances at inevitably twelve of the remotest and most rinky-dink schools in America. On the whole, she opined, it was a pretty easy way to make a living. Just horribly boring, until life-of-the-party Yalies like Karen and myself happened to turn up.

I think we might well have kidnapped Susan and carried her home to Connecticut to drink, smoke, and argue music and films indefinitely, but she was escorted by her son, David Rieff, who took the responsibility for keeping Susan on track. In the end, Susan et fils went off to pay their dues by giving some attention to the Blooomsburg college’s factotums, and bidding her a fond farewell, Karen and I went off to catch the evening hatch.

It was a few months later that I next ran into Sontag. I had gone to the Bleeker Street Cinena to catch an 11 AM showing of Mizoguchi’s “Ugetsu” (1954). A familiar figure was standing in the ticket line, and (not wanting to announce her identity to the crowd) I merely walked over and said: “I believe that you are the lady I met recently in Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania.” Sontag recognized me, cracked up, and we wound up sitting together through the film. Sontag and I had, history demonstrates, a similar taste in the cinema, so we ran into each other repeatedly in theater lobbies. If Sontag was in company, we would wave and smile, but if she was alone, we would sit together.

The cultural life of New York City typically runs to one terribly-important event per season. Back in the period in which I was living or working in New York, Karen and I would reliably be attending that event and, of course, so would Susan Sontag. We ran into Susan at a number of these, and got to sit with her a few times. At the Radio City Music Hall showing of the rediscovered and restored print of Abel Gance’s “Napoleon” (1927), Sontag somehow arranged to have us placed beside her and her companion, the aged, but extremely witty, Lillian Gish. Cinemaphiles watching a silent movie can have an especially good time, since it is perfectly possible to chat continuously and to exchange critical or humorous observations throughout the viewing without actually spoiling the movie.

Sontag also introduced us to Stephen Spielberg and George Lucas at the Lincoln Center showing of Syberberg’s “Parzifal” (1982).

My own experience of Susan Sontag was clearly a good deal different from Terry Castle’s. I found that, if one could talk to Susan Sontag on her own level and if one could entertain and amuse her, one’s personal lack of celebrity status was not really a problem. Of course, neither Karen nor I were ever involved with her romantically, and our entire relationship was based merely upon happenstance runnings into one another. We never made any effort to enlarge our acquaintanceship and we never made any demands upon her.

I did once make a serious effort to persuade Susan Sontag to come over to the Conservative political camp (unsuccessfully), but that is another story.

09 Sep 2014

Emily St. John Mandel, in Humanities, discusses a new documentary, Regarding Susan Sontag, on the life and personality of the renowned critic and intellectual.

I was going to embed the trailer but, when I looked at it, I thought it was a completely distortive crock which was attempting, unnecessarily, to ramp up excitement over its subject by misleadingly portraying Sontag as some kind of danger-loving war correspondent and street-fighting activist.

Sontag, of course, was neither of the above. What she was was really an extraordinarily gifted and extraordinarily passionate autodidact, who by force of will lifted herself from 1950s American suburbia to a position of international fame as a critic, author, and engagée public intellectual.

The film apparently accurately, unlike the trailer, devotes itself to paying tribute to Sontag’s omniverous intellectual enthusiasm and unbridled capacity for taking pleasure in the exercise of the mind.

Reflecting on the collapse of his marriage with Sontag, in a story that appeared in the New York Observer a year after her death, Philip Rieff said, “I think what I wanted was a large family and what she wanted was a large library.â€

Hat tip to Karen L. Myers.

06 May 2013

Susan Sontag

Maria Popova discusses lists and shares a 1977 list of Susan Sontag’s likes and dislikes.

Things I like: fires, Venice, tequila, sunsets, babies, silent films, heights, coarse salt, top hats, large long-haired dogs, ship models, cinnamon, goose down quilts, pocket watches, the smell of newly mown grass, linen, Bach, Louis XIII furniture, sushi, microscopes, large rooms, ups, boots, drinking water, maple sugar candy.

Things I dislike: sleeping in an apartment alone, cold weather, couples, football games, swimming, anchovies, mustaches, cats, umbrellas, being photographed, the taste of licorice, washing my hair (or having it washed), wearing a wristwatch, giving a lecture, cigars, writing letters, taking showers, Robert Frost, German food.

Things I like: ivory, sweaters, architectural drawings, urinating, pizza (the Roman bread), staying in hotels, paper clips, the color blue, leather belts, making lists, Wagon-Lits, paying bills, caves, watching ice-skating, asking questions, taking taxis, Benin art, green apples, office furniture, Jews, eucalyptus trees, pen knives, aphorisms, hands.

Things I dislike: Television, baked beans, hirsute men, paperback books, standing, card games, dirty or disorderly apartments, flat pillows, being in the sun, Ezra Pound, freckles, violence in movies, having drops put in my eyes, meatloaf, painted nails, suicide, licking envelopes, ketchup, traversins [“bolstersâ€], nose drops, Coca-Cola, alcoholics, taking photographs.

Things I like: drums, carnations, socks, raw peas, chewing on sugar cane, bridges, Dürer, escalators, hot weather, sturgeon, tall people, deserts, white walls, horses, electric typewriters, cherries, wicker / rattan furniture, sitting cross-legged, stripes, large windows, fresh dill, reading aloud, going to bookstores, under-furnished rooms, dancing, Ariadne auf Naxos.

05 Apr 2011

The late Susan Sontag’s hyperintellectual perspective was formed as part of the post-WWII Beat, Queer, Żydokomuna (a Polish term for the well-known Jewish cultural penchant for Marxism) international left-wing counter-cultural intelligentsia. Sontag actually broke with the left in the early 1980s, after the news of what had happened in Cambodia came out, but inevitably over the course of her long literary career, Susan Sontag was normally to be found in the mainstream of contemporary political fashion, and she several times went on the record saying very foolish things.

In Saturday’s Wall Street Journal, the sharp-tongued Joseph Epstein took the occasion of the publication of a new memoir of life with Sontag by one of her former minions, Sempre Susan: A Memoir of Susan Sontag , to deliver some just criticism for some of Sontag’s worst statements and behavior and to put her in her place in cultural history once and for all. , to deliver some just criticism for some of Sontag’s worst statements and behavior and to put her in her place in cultural history once and for all.

In Epstein’s view, Susan Sontag was just a pretty girl with a remarkable gift for self-promotion.

A single essay, “Notes on ‘Camp,'” published in Partisan Review in 1964, launched Susan Sontag’s career, at the age of 31, and put her instantly on the Big Board of literary reputations. People speak of ideas whose time has not yet come; hers was a talent for promoting ideas that arrived precisely on time. “Notes on ‘Camp,'” along with a companion essay called “Against Interpretation,” vaunted style over content: “The idea of content,” Ms. Sontag wrote, “is today merely a hindrance, a subtle or not so subtle philistinism.” She also held interpretation to be “the enemy of art.” She argued that Camp, a style marked by extravagance, epicene in character, expressed a new sensibility that would “dethrone the serious.” In its place she would put, with nearly equal standing, such cultural items as comic books, wretched movies, pornography watched ironically, and other trivia.

These essays arrived as the 1960s were about to come to their tumultuous fruition and provided an aesthetic justification for a retreat from the moral judgment of artistic works and an opening to hedonism, at least in aesthetic matters. “In place of a hermeneutics,” Sontag’s “Against Interpretation” ended, “we need an erotics of art.” She also argued that the old division between highbrow and lowbrow culture was a waste not so much of time as of the prospects for enjoyment. Toward this end she lauded the movies –cinema is the active, the most exciting, the most important of all the art forms right now –as well as science fiction and popular music.

These cultural pronunciamentos, authoritative and richly allusive, were delivered in a mandarin manner. They read as if they were a translation, probably, if one had to guess, from the French. They would have been more impressive, of course, if their author were herself a first-class artist. This, Lord knows, Susan Sontag strained to be. She wrote experimental fiction that never came off; later in her career she wrote more traditional fiction, but it, too, arrived dead on the page.

The problem is that Sontag wasn’t sufficiently interested in real-life details, the lifeblood of fiction, but only in ideas. She also wrote and directed films, which were not well-reviewed: I have not seen these myself, but there is time enough to do so, for I have long assumed that they are playing as a permanent double feature in the only movie theater in hell.

Ouch!

Good abuse, but not entirely just. True, Susan Sontag yearned to write important novels, to score a breakthrough with some plus nouveaux nouveau roman and also to rise to the level of auteur in the most challenging regions of the cinema where she felt herself most at home as a critic and a fan. And it is true that she was not particularly successful as a novelist. Her earlier novels The Benefactor and Death Kit were formalist experiments whose only excellence lay in inducing sleep with certainty. Her later novels seemed to me even less interesting.

Her films were clearly not successful. I cannot defend or criticize her four films, as I too am waiting to see them repeatedly in the hereafter with mild alarm. But Sontag does deserve better on the basis of her essays and her criticism.

It is easy to mock the manifesto calling for criticism as an erotics of art, rather than a hermeneutics. Susan Sontag’s rhetoric and critical aspirations were bold and uninhibited and a trifle prone to overreach, but her critical essays were also a breath of fresh and exotic air blowing into middlebrow American culture from the heights of Montparnasse.

Countless Americans found their way to the accessible cinema of Bergman, Fellini, and Truffaut beckoned by the beacon of Sontag’s travelogues from the remote and inaccessible regions of Antonioni, Bresson, and Ozu. Sontag made the concept of the avante-garde into the art cinema’s equivalent of “the banner with a strange device.”

It was not enough, this passionate young woman persuaded readers, to appreciate the familiar and the beautiful, it was necessary to press on, to leap beyond present artistic and cultural forms of understanding and expression, to conquer strange new heights and plumb unprecedented depths. Susan Sontag seemed, back then, a cultural Joan of Arc, leading the literary and cinematic audience forward in a headlong assault on possibility and the existing state of literature and the arts in a brave and determined effort to break through the barriers and liberate new forms of cultural expression and understanding.

Today, when I watch Last Year at Marienbad or L’Aventurra, when I look into a novel by Nathalie Saurraute, I feel rather the way a veteran of a lost, romantic cause, like some aged grenadier of the wars of Napoleon, must have felt thinking back and remembering Austerlitz or Marengo. I smile ruefully at the memory of being young and naive enough to believe that this sort of thing would come to anything, but I also remember the aspirations and the hopes we entertained back then.

Susan Sontag is extremely vulnerable to all the criticisms to which mainsteam Western high culture in the second half of the last century is vulnerable. She was naively romantic, prone to left-wing postures and insanity, and not above following the community of fashion herd into disgraceful positions. But she was still a heroine who, at times, at least, brought great honor to that same high culture and the same civilization her entire class was usually busy trying to destroy.

I knew her a little, and when I lived in New York, I would exchange greetings with her at the kind of key cultural events at which we would both invariably be present. I would also run into her sometimes at the revival houses, and we occasionally sat together and watched Mizoguchi or Renoir at Bleeker Street. Perhaps someday at the cinema in Tartarus mentioned by Mr. Epstein, I can sit beside her and discuss Duet for Cannibals and Brother Carl.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Susan Sontag' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|