Category Archive 'The Last Man'

05 Jul 2018

Michel Houellebecq

Slawomir Sierakowski interviewing Slavoj Žižek back in 2015 after the Charlie Hebdo murders.

Do you see common ground between you and Michel Houellebecq, with his critique of Western liberal societies, combined with no justification for reactionary alternatives like Islamist or Russian ones?

Yes, definitely. Crazy as it may sound, I have much respect for the honest liberal conservatives like Houellebecq, Finkielkraut, or Sloterdijk in Germany. One can learn from them much more than from progressive liberal like Habermas: honest conservatives are not afraid to admit the deadlock we are in. Houellebecq’s Atomised is for me the most devastating portrait of the sexual revolution of the 1960s. He shows how permissive hedonism turns into the obscene superego universe of the obligation to enjoy. Even his anti-Islamism is more refined than it may appear: he is well aware how the true problem is not the Muslim threat from the outside, but our own decadence. Long ago Friedrich Nietzsche perceived how Western civilization was moving in the direction of the Last Man, an apathetic creature with no great passion or commitment. Unable to dream, tired of life, he takes no risks, seeking only comfort and security, an expression of tolerance with one another:

A little poison now and then: that makes for pleasant dreams. And much poison at the end, for a pleasant death. They have their little pleasures for the day, and their little pleasures for the night, but they have a regard for health. “We have discovered happiness,†— say the Last Men, and they blink.

RTWT

01 Oct 2015

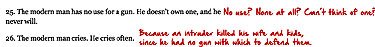

Via Karen L. Myers and Ed Driscoll at Instapundit, a NYT column defining “The Modern Man” with replies in red ink.

15 Sep 2014

Gustave Dore, Orlando Furioso

From Slavoj Zizek’s How to Read Lacan:

The problem for the hysteric is how to distinguish what he or she is (his true desire) from what others see and desire in him or her. This brings us to another of Lacan’s formulas, that “man’s desire is the other’s desire.” For Lacan, the fundamental impasse of human desire is that it is the other’s desire in both subjective and objective genitive: desire for the other, desire to be desired by the other, and, especially, desire for what the other desires. Envy and resentment are a constitutive component of human desire, as already Augustin knew it so well – recall the passage from his Confessions, often quoted by Lacan, which describes a baby jealous of his brother sucking the mother’s breast: “I myself have seen and known an infant to be jealous though it could not speak. It became pale, and cast bitter looks on its foster-brother.” Based on this insight, Jean-Pierre Dupuy proposed a convincing critique of John Rawls theory of justice: in the Rawls’ model of a just society, social inequalities are tolerated only insofar as they also help those at the bottom of the social ladder, and insofar as they are not based on inherited hierarchies, but on natural inequalities, which are considered contingent, not merits. What Rawls doesn’t see is how such a society would create conditions for an uncontrolled explosion of resentment: in it, I would know that my lower status is fully justified, and would be deprived of excusing my failure as the result of social injustice.

Rawls proposes a terrifying model of a society in which hierarchy is directly legitimized in natural properties, missing the simple lesson of an anecdote about a Slovene peasant who is told by a good witch: “I will do to you whatever you want, but I warn you, I will do it to your neighbor twice!” The peasant, with a cunning smile, asks her: “Take one of my eyes!” No wonder that even today’s conservatives are ready to endorse Rawls’s notion of justice: in December 2005, David Cameron, the newly elected leader of the British Conservatives, signaled his intention to turn the Conservative Party into a defender of the underprivileged, declaring how “I think the test of all our policies should be: what does it do for the people who have the least, the people on the bottom rung of the ladder.” Even Friedrich Hayek.

Lacan shares with Nietzsche and Freud the idea that justice as equality is founded on envy: the envy of the other who has what we do not have, and who enjoys it. The demand for justice is ultimately the demand that the excessive enjoyment of the other should be curtailed, so that everyone’s access to enjoyment will be equal. The necessary outcome of this demand, of course, is ascetism: since it is not possible to impose equal enjoyment, what one can impose is the equally shared prohibition. However, one should not forget that today, in our allegedly permissive society, this ascetism assumes precisely the form of its opposite, of the generalized injunction “Enjoy!”. We are all under the spell of this injunction, with the outcome that our enjoyment is more hindered than ever – recall the yuppie who combines Narcissistic Self-Fulfillment with utter ascetic discipline of jogging and eating health food. This, perhaps, is what Nietzsche had in mind with his notion of the Last Man – it is only today that we can really discern the contours of the Last Man, in the guise of the predominant hedonistic ascetism. In today’s market, we find a whole series of products deprived of their malignant property: coffee without caffeine, cream without fat, beer without alcohol… and the list goes on. What about virtual sex as sex without sex, the Colin Powell doctrine of warfare with no casualties (on our side, of course) as warfare without warfare, the contemporary redefinition of politics as the art of expert administration as politics without politics, up to today’s tolerant liberal multiculturalism as an experience of Other deprived of its Otherness (the idealized Other who dances fascinating dances and has an ecologically sound holistic approach to reality, while features like wife beating remain out of sight)? Virtual reality simply generalizes this procedure of offering a product deprived of its substance: it provides reality itself deprived of its substance, of the resisting hard kernel of the Real – in the same way decaffeinated coffee smells and tastes like real coffee without being the real one, Virtual Reality is experienced as reality without being one. Everything is permitted, you can enjoy everything – on condition that it is deprived of the substance which makes it dangerous.

Jenny Holzer’s famous truism “Protect me from what I want” renders in a very precise way the fundamental ambiguity of the hysterical position.

07 Jun 2010

Peter Singer

…for many a time

I have been half in love with easeful Death,

Call’d him soft names in many a mused rhyme,

To take into the air my quiet breath;

Now more than ever seems it rich to die,

To cease upon the midnight with no pain.

–John Keats

In the New York Times, Princeton’s professional ethicist supreme Peter Singer admires the work of antinatalist South African philosopher David Benatar:

Schopenhauer’s pessimism has had few defenders over the past two centuries, but one has recently emerged, in the South African philosopher David Benatar, author of a fine book with an arresting title: “Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence.†One of Benatar’s arguments trades on something like the asymmetry noted earlier. To bring into existence someone who will suffer is, Benatar argues, to harm that person, but to bring into existence someone who will have a good life is not to benefit him or her. Few of us would think it right to inflict severe suffering on an innocent child, even if that were the only way in which we could bring many other children into the world. Yet everyone will suffer to some extent, and if our species continues to reproduce, we can be sure that some future children will suffer severely. Hence continued reproduction will harm some children severely, and benefit none.

Benatar also argues that human lives are, in general, much less good than we think they are. We spend most of our lives with unfulfilled desires, and the occasional satisfactions that are all most of us can achieve are insufficient to outweigh these prolonged negative states. If we think that this is a tolerable state of affairs it is because we are, in Benatar’s view, victims of the illusion of pollyannaism. This illusion may have evolved because it helped our ancestors survive, but it is an illusion nonetheless. If we could see our lives objectively, we would see that they are not something we should inflict on anyone.

Here is a thought experiment to test our attitudes to this view. Most thoughtful people are extremely concerned about climate change. Some stop eating meat, or flying abroad on vacation, in order to reduce their carbon footprint. But the people who will be most severely harmed by climate change have not yet been conceived. If there were to be no future generations, there would be much less for us to feel to guilty about.

So why don’t we make ourselves the Last Generation on Earth? If we would all agree to have ourselves sterilized then no sacrifices would be required — we could party our way into extinction! …

Is a world with people in it better than one without? Put aside what we do to other species — that’s a different issue. Let’s assume that the choice is between a world like ours and one with no sentient beings in it at all. And assume, too — here we have to get fictitious, as philosophers often do — that if we choose to bring about the world with no sentient beings at all, everyone will agree to do that. No one’s rights will be violated — at least, not the rights of any existing people. Can non-existent people have a right to come into existence?

I do think it would be wrong to choose the non-sentient universe. In my judgment, for most people, life is worth living. Even if that is not yet the case, I am enough of an optimist to believe that, should humans survive for another century or two, we will learn from our past mistakes and bring about a world in which there is far less suffering than there is now. But justifying that choice forces us to reconsider the deep issues with which I began. Is life worth living? Are the interests of a future child a reason for bringing that child into existence? And is the continuance of our species justifiable in the face of our knowledge that it will certainly bring suffering to innocent future human beings?

Friedrich Nietszche (Thus Spake Zarathustra, 1883-1885, prologue, §5) predicted with complete accuracy that the result of nihilism would be Benatars and Singers.

Alas! There cometh the time when man will no longer give birth to any star. Alas! There cometh the time of the most despicable man, who can no longer despise himself.

Lo! I show you THE LAST MAN.

“What is love? What is creation? What is longing? What is a star?”–so asketh the last man and blinketh.

The earth hath then become small, and on it there hoppeth the last man who maketh everything small. His species is ineradicable like that of the ground-flea; the last man liveth longest.

“We have discovered happiness”–say the last men, and blink thereby.

They have left the regions where it is hard to live; for they need warmth. One still loveth one’s neighbour and rubbeth against him; for one needeth warmth.

Turning ill and being distrustful, they consider sinful: they walk warily. He is a fool who still stumbleth over stones or men!

A little poison now and then: that maketh pleasant dreams. And much poison at last for a pleasant death.

One still worketh, for work is a pastime. But one is careful lest the pastime should hurt one.

One no longer becometh poor or rich; both are too burdensome. Who still wanteth to rule? Who still wanteth to obey? Both are too burdensome.

No shepherd, and one herd! Every one wanteth the same; every one is equal: he who hath other sentiments goeth voluntarily into the madhouse.

“Formerly all the world was insane,”–say the subtlest of them, and blink thereby.

They are clever and know all that hath happened: so there is no end to their raillery. People still fall out, but are soon

reconciled–otherwise it spoileth their stomachs.

They have their little pleasures for the day, and their little pleasures for the night, but they have a regard for health.

“We have discovered happiness,”–say the last men, and blink thereby.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'The Last Man' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|