Category Archive 'English Department'

15 Sep 2020

University of Chicago

Faculty Statement (July 2020):

The English department at the University of Chicago believes that Black Lives Matter, and that the lives of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, and Rayshard Brooks matter, as do thousands of others named and unnamed who have been subject to police violence. As literary scholars, we attend to the histories, atmospheres, and scenes of anti-Black racism and racial violence in the United States and across the world. We are committed to the struggle of Black and Indigenous people, and all racialized and dispossessed people, against inequality and brutality.

For the 2020-2021 graduate admissions cycle, the University of Chicago English Department is accepting only applicants interested in working in and with Black Studies. We understand Black Studies to be a capacious intellectual project that spans a variety of methodological approaches, fields, geographical areas, languages, and time periods. For more information on faculty and current graduate students in this area, please visit our Black Studies page.

The department is invested in the study of African American, African, and African diaspora literature and media, as well as in the histories of political struggle, collective action, and protest that Black, Indigenous and other racialized peoples have pursued, both here in the United States and in solidarity with international movements. Together with students, we attend both to literature’s capacity to normalize violence and derive pleasure from its aesthetic expression, and ways to use the representation of that violence to reorganize how we address making and breaking life. Our commitment is not just to ideas in the abstract, but also to activating histories of engaged art, debate, struggle, collective action, and counterrevolution as contexts for the emergence of ideas and narratives.

English as a discipline has a long history of providing aesthetic rationalizations for colonization, exploitation, extraction, and anti-Blackness. Our discipline is responsible for developing hierarchies of cultural production that have contributed directly to social and systemic determinations of whose lives matter and why. And while inroads have been made in terms of acknowledging the centrality of both individual literary works and collective histories of racialized and colonized people, there is still much to do as a discipline and as a department to build a more inclusive and equitable field for describing, studying, and teaching the relationship between aesthetics, representation, inequality, and power.

In light of this historical reality, we believe that undoing persistent, recalcitrant anti-Blackness in our discipline and in our institutions must be the collective responsibility of all faculty, here and elsewhere. In support of this aim, we have been expanding our range of research and teaching through recent hiring, mentorship, and admissions initiatives that have enriched our department with a number of Black scholars and scholars of color who are innovating in the study of the global contours of anti-Blackness and in the equally global project of Black freedom. Our collective enrichment is also a collective debt; this department reaffirms the urgency of ensuring institutional and intellectual support for colleagues and students working in the Black studies tradition, alongside whom we continue to deepen our intellectual commitments to this tradition. As such, we believe all scholars have a responsibility to know the literatures of African American, African diasporic, and colonized peoples, regardless of area of specialization, as a core competence of the profession.

RTWT

You could as easily accuse any university English Department of systematically being anti-Lithuanian, anti-French, anti-Japanese, or anti-Eskimo (excuse me! Inuit) for its shameful neglect of the artistic legacy of any, or all, of the above, and for its “aesthetic rationalizations” of the unequal representation of Lithuanians, Frenchmen, &c. in their universities’ student bodies, in high-paying elite positions in American investment banks and Wall Street Law Firms, and in Supreme Court Appointments.

Personally, I think sane people with a deep interest in English Literature are just as well off not studying under such a collection of lachrymose and deranged Marxists as apparently currently infest Chicago’s English Department.

That distant buzzing sound you hear is the late Allan Bloom, author of The Closing of the American Mind: How Higher Education Has Failed Democracy and Impoverished the Souls of Today’s Students, spinning in his grave at 78 rpm.

22 Jun 2016

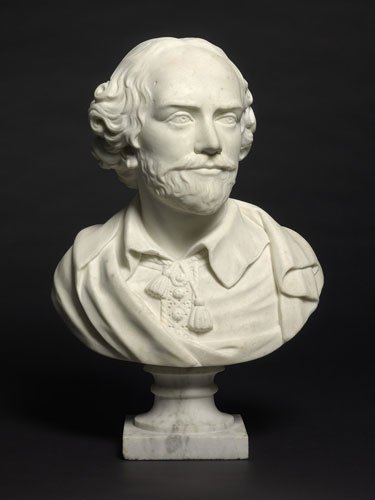

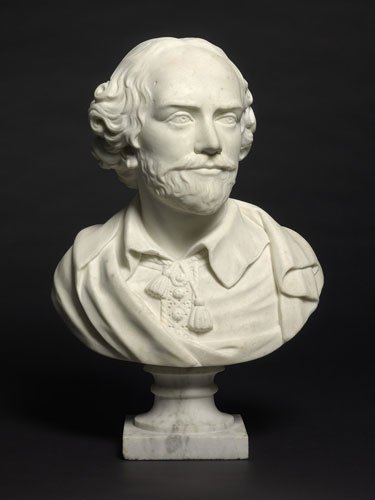

Shakespeare: Male, White, Christian, Married with Children, Get Over it.

Last month, 160 students in Yale’s (once first in the nation) English Department signed a petition demanding that the department “reevaluate the undergraduate curriculum, as well as reconsider the current core requirements and introductory courses… particularly .. the Major English Poets sequence, a longtime prerequisite for the major and “perhaps the most distinctive element of English at Yale.†The petition called for the removal of this prerequisite for the English major and for requirements “to refocus and include literature relating to gender, race and sexuality.” (Yale Daily News, May 26)

It appears that Yale’s current English Department Chairman, Langdon Hammer (a specialist in the likes of James Merrill and Hart Crane; Finalist, Lambda Literary Award for Gay Memoir/Biography, 2016; Larry Kramer Initiative for Gay and Lesbian Studies at Yale, 2003) intends to cave, while denying that that is what he is doing.

Professor Hammer (appropriately named like a character in a satirical novel by Evelyn Waugh) announced recently via the English Department news:

English 125/6 is a course that introduces students to a particular literary tradition, and the course itself has the status of a tradition. The thing about literary traditions is, they are always being upended and remade. That is the history of English poetry from Chaucer to Eliot (or to Hughes or Stein or Bishop or Walcott or Glück, who were all taught this spring in one or another section of this multi-section course). So it seems fitting for students and faculty to raise questions about the course and its role in the major.

The questions on my mind about English 125/6 are: How can this course be made better? What is its relationship to the rest of the English Department curriculum? What should and shouldn’t the faculty require of its majors? What does a strong education in the discipline of English look like today? And what should it look like tomorrow?

The English Department faculty is charged with asking those questions about all of our courses. We ask them in formal and informal ways every year, and we will again next year. We’ll be in conversation with our students, who have a range of views. And we’ll make decisions about what we teach and what we ask of students that seem appropriate to us.

The invertebrates in charge at Yale these days are always “having conversations” with the barbarians of the Left over insane and insolent demands delivered by the latter. These conversatione invariably amount to duplicitous attempts to save face and avoid the wrath of reactionary alumni by surrendering as little as possible to appease all the little Calibans they have intentionally admitted via extraordinary efforts and indulgences to the magic island. But there is always a surrender.

The sound you hear, in the distance, is all the great English professors of the past spinning in their graves as Langston Hughes replaces Milton and Dereck Walcott replaces Chaucer in Yale’s version of the canon.

29 Sep 2009

Willam M. Chace, in the American Scholar, identifies the decline in study of the Humanities in general with the internal collapse of the English Department following the overthrow of the idea of the canon.

Perhaps the most telling sign of the near bankruptcy of the discipline is the silence from within its ranks. In the face of one skeptical and disenchanted critique after another, no one has come forward in years to assert that the study of English (or comparative literature or similar undertakings in other languages) is coherent, does have self-limiting boundaries, and can be described as this but not that.

Such silence strongly suggests a complicity of understanding, with the practitioners in agreement that to teach English today is to do, intellectually, what one pleases. No sense of duty remains toward works of English or American literature; amateur sociology or anthropology or philosophy or comic books or studies of trauma among soldiers or survivors of the Holocaust will do. You need not even believe that works of literature have intelligible meaning; you can announce that they bear no relationship at all to the world beyond the text. Nor do you need to believe that literary history is helpful in understanding the books you teach; history itself can be shucked aside as misleading, irrelevant, or even unknowable. In short, there are few, if any, fixed rules or operating principles to which those teaching English and American literature are obliged to conform. With everything on the table, and with foundational principles abandoned, everyone is free, in the classroom or in prose, to exercise intellectual laissez-faire in the largest possible way—I won’t interfere with what you do and am happy to see that you will return the favor. Yet all around them a rich literature exists, extraordinary books to be taught to younger minds.

Consider the English department at Harvard University. It has now agreed to remove its survey of English literature for undergraduates, replacing it and much else with four new “affinity groupsâ€â€”“Arrivals,†“Poets,†“Diffusions,†and “Shakespeares.†The first would examine outside influences on English literature; the second would look at whatever poets the given instructor would select; the third would study various writings (again, picked by the given instructor) resulting from the spread of English around the globe; and the final grouping would direct attention to Shakespeare and his contemporaries.

Daniel Donoghue, the department’s director of undergraduate studies, told The Harvard Crimson last December that “our approach was to start with a completely clean slate.†And Harvard’s well-known Shakespeare scholar Stephen Greenblatt also told the Crimson that the substance of the old survey will “trickle down to students through the professors themselves who, after all, specialize in each of these areas of English literature.†But under the proposal, there would be no one book, or family of books, that every English major at Harvard would have read by the time he or she graduates. The direction to which Harvard would lead its students in this “clean slate†or “trickle down†experiment is to suspend literary history, thrusting into the hands of undergraduates the job of cobbling together intellectual coherence for themselves. Greenblatt puts it this way: students should craft their own literary “journeys.†The professors might have little idea of where those journeys might lead, or how their paths might become errant. There will be no common destination.

As Harvard goes, so often go the nation’s other colleges and universities. Those who once strove to give order to the curriculum will have learned, from Harvard, that terms like core knowledge and foundational experience only trigger acrimony, turf protection, and faculty mutinies. No one has the stomach anymore to refight the Western culture wars. Let the students find their own way to knowledge.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'English Department' Category.

Feeds

|