Category Archive 'American Medical Association'

09 May 2017

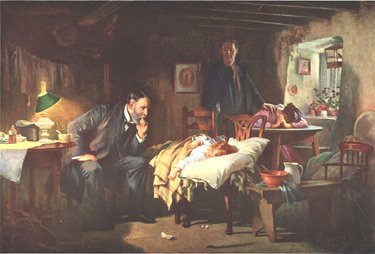

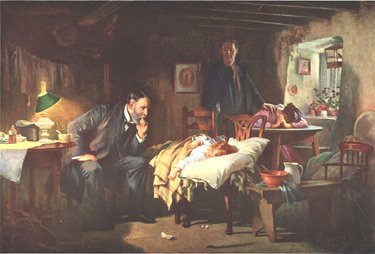

In 1949, Sir Samuel Fildes’ painting “The Doctor†(1891) was used by the American Medical Association in a campaign against a proposal for nationalized medical care put forth by President Harry S. Truman. The image was used in posters and brochures along with the slogan, “Keep Politics Out of this Picture.†65,000 posters of The Doctor were distributed, which helped to raise public skepticism of the nationalized health care campaign. By 2008,

unfortunately, the AMA was controlled by the Left and fighting for doctors’ and patients’ rights to private health care was no longer part of its agenda.

Kevin Williamson debunks the “Health Care is a right!” rhetoric.

With the American Health Care Act dominating the week’s news, one conversation has been unavoidable: Someone — someone who pays attention to public policy — will suggest that we pursue policy x, y, or z, and someone else — someone who pays a little less careful attention, who probably watches a lot of cable-television entertainment masquerading as news — responds: “The first thing we have to do is acknowledge that health care is a human right!†What follows is a moment during which the second speaker visibly luxuriates in his display of empathy and virtue, which is, of course, the point of the exercise. …

Here is a thought experiment: You have four children and three apples. You would like for everyone to have his own apple. You go to Congress, and you successfully persuade the House and the Senate to endorse a joint resolution declaring that everyone has a right to an apple of his own. A ticker-tape parade is held in your honor, and you share your story with Oprah, after which you are invited to address the United Nations, which passes the International Convention on the Rights of These Four Kids in Particular to an Individual Apple Each. You are visited by the souls of Mohandas Gandhi and Mother Teresa, who beam down approvingly from a joint Hindu-Catholic cloud in Heaven. Question: How many apples do you have? You have three apples, dummy. Three. You have four children. Each of those children has a congressionally endorsed, U.N.-approved, saint-ratified right to an apple of his own. But here’s the thing: You have three apples and four children. Nothing has changed. Declaring a right in a scarce good is meaningless. It is a rhetorical gesture without any application to the events and conundrums of the real world. If the Dalai Lama were to lead 10,000 bodhisattvas in meditation, and the subject of that meditation was the human right to health care, it would do less good for the cause of actually providing people with health care than the lowliest temp at Merck does before his second cup of coffee on any given Tuesday morning. Health care is physical, not metaphysical. It consists of goods, such as penicillin and heart stents, and services, such as oncological attention and radiological expertise. Even if we entirely eliminated money from the equation, conscripting doctors into service and nationalizing the pharmaceutical factories, the basic economic question would remain. We tend to retreat into cheap moralizing when the economic realities become uncomfortable for us. No matter the health-care model you choose — British-style public monopoly, Swiss-style subsidized insurance, pure market capitalism — you end up with rationing: Markets ration through prices, bureaucracies ration through politics.

RTWT

Claiming that you have a “Right to Health Care” usually amounts to the assertion that you have a right to force somebody else to pay for goods and services for your benefit, in essence a claim that you have a right to enslave other people.

———————————

Avik Roy puts it a different way. Avik argues that our right to health care consists of our right to obtain health services through voluntary interactions with health care providers, and Government is taking away that right.

For those enrolled in government-run health insurance, it is illegal to try to gain better access to doctors and dentists by offering to make up the difference between what health care costs, and what the government pays.

That basic right—the right of a woman and her doctor to freely exchange money for a needed medical service—is one that 90 million Americans have been denied by their government. …

You see, health care is a right, in the same way that liberty is a right. And that liberty—to freely seek the care we need, to pay for it in a way that is mutually convenient for us and our doctors, is one that our government is gradually taking out of our hands.

RTWT

18 Mar 2017

Sir Samuel Luke Fildes KCVO RA, The Doctor, 1891, Tate Gallery.

In 1949, Fildes’ painting “The Doctor” (1891) was used by the American Medical Association in a campaign against a proposal for nationalized medical care put forth by President Harry S. Truman. The image was used in posters and brochures along with the slogan, “Keep Politics Out of this Picture.” 65,000 posters of The Doctor were distributed, which helped to raise public skepticism of the nationalized health care campaign. In 2008, the AMA was no longer defending the sanctity of the doctor-patient relationship and the independence of the Medical Profession, but was instead supporting Obamacare and the nationalization of health care.

Dr. Publius, at Ricochet, explains how all this happened.

For the medical profession, there is one ethical obligation that surpasses all others. It is the very obligation that defines a classic profession, and once it is abandoned, members of that so-called profession no longer have any claim whatsoever to any of the special regard, respect, perquisites, or considerations that commonly accrue to true professionals in our society.

Physicians have referred to this obligation as the doctor-patient relationship. Like the lawyer-client relationship and the clergy-parishioner relationship, the doctor-patient relationship is supposed to be a sacred, protected, fiduciary one, in which the patient can feel safe in disclosing private information they may not even willingly tell their spouses, and in return the doctor agrees not only to keep that information private, but also to act on that information in such a way that furthers and optimizes the individual patient’s own best medical interests, without regard to which actions or recommendations might be to the doctor’s interests — or to society’s.

The abandonment of this sacred, fiduciary obligation (honored by physicians for over 2000 years) cannot be blamed on Obamacare. It was formally abandoned years before most of us had ever heard of Mr. Obama. The doctor-patient relationship, never as pure in practice as it was in concept, began to significantly erode in the 1990s. This, of course, was the heyday of for-profit HMOs, when the insurers used extreme coercion to make certain that doctors learned who their real customers were. Doctors who did not place the payers first had their reimbursements slashed, and often found themselves excluded from panels, and therefore from access to patients. In a surprisingly short time doctors by the thousands were signing “gag clauses,†in which they agreed to withhold from patients certain information that might be adverse to the interests of the HMOs.

It would be wrong to say that doctors did not mind these things. It troubled many of them deeply. Indeed, by the turn of the millennium many members of the profession were feeling, and occasionally publicly expressing, tremendous guilt for having had to abandon their chief ethical obligation to their patients, in order to continue practicing medicine.

Faced with an ethical dilemma which was increasingly difficult for them to tolerate, an outcry arose from within the medical profession demanding that their leadership take up the problem, and do something about it. Most doctors had in mind some sort of organized action by which the profession would attempt to reclaim its ethical grounding. And so, conferences were convened, debates (of a sort) engaged in, and at last, action taken.

What doctors in the trenches failed to realize was that the physicians who dedicate their careers to leading professional organizations are almost always Progressives, because this is what Progressives do. So the action that was finally taken was the official adoption of a new set of medical ethics, which was published in 2002: “Medical Professionalism in the New Millennium: A Physician Charter. “(Annals of Internal Medicine, February 5, 2002). This document described a new ethical precept which was to be formally adopted by the medical profession. That new precept was, of course, “Social Justice.†Under the precept of social justice, doctors, in making medical decisions at the bedside, suddenly became obligated to take the equitable distribution of healthcare resources into account. Covert rationing at the bedside at the behest of payers (who presumably knew more about equitable distribution of resources than individual physicians did), was not only acceptable, and not only a positive good, but an ethical requirement.

During the intervening years this new charter of medical ethics was indeed formally adopted by virtually every medical professional organization in the world.

Adding social justice to the ethical obligations of physicians or course did nothing to ease the discrepancy between the needs the patient and the needs of the payer. But its addition at least assuaged some of the guilt of some of the doctors who chose not to think too deeply about it.

This modernized, progressive version of medical ethics was not the result of Obamacare, but it has served Obamacare well. It was a matter of mere moments before doctors noticed that it would behoove them to shift their efforts from making the insurers happy to making the government happy.

Today, when a doctor makes a medical recommendation to a patient, that patient can no longer be confident that the recommendation is truly the one the doctor believes is best for him or her. For it may instead simply represent what the doctor has decided the patient deserves, given his/her needs in relation to the needs of all the other patients in the Accountable Care Organization, the state, the country, or the world.

12 Jun 2006

We can apply to doctors Goethe’s famous rueful comment on the German people: “so estimable in the individual and so wretched in the generality.”

story

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'American Medical Association' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|