Category Archive 'Hellenistic Art'

29 Jul 2019

The Independent reports on a surprising breakthrough in our understanding of Qin Dynasty China.

Ancient Greeks artists could have travelled to China 1,500 years before Marco Polo’s historic trip to the east and helped design the famous Terracotta Army, according to new research.

The startling claim is based on two key pieces of evidence: European DNA discovered at sites in China’s Xinjiang province from the time of the First Emperor in the Third Century BC and the sudden appearance of life-sized statues.

Before this time, depictions of humans in China are thought to have been figurines of up to about 20cm.

But 8,000 extraordinarily life-like terracotta figures were found buried close to the massive tomb of China’s First Emperor, Qin Shi Huang, who unified the country in 221BC.

The theory – outlined in a documentary, The Greatest Tomb on Earth: Secrets of Ancient China, to be shown on BBC Two on Sunday – is that Shi Huang and Chinese artists may have been influenced by the arrival of Greek statues in central Asia in the century following Alexander the Great, who led an army into India.

But the researchers also speculated that Greek artists could have been present when the soldiers of the Terracotta Army were made.

One of the team, Professor Lukas Nickel, chair of Asian art history at Vienna University, said: “I imagine that a Greek sculptor may have been at the site to train the locals.â€

Other evidence of connections to Greece came from a number of exquisite bronze figurines of birds excavated from the tomb site. These were made with a lost wax technique known in Ancient Greece and Egypt.

There was a breakthrough in sculpture particularly in ancient Athens at about the time when the city became a democracy in the 5th century BC.

Previously, human figures have been stiff and stylised representations, but the figures carved on the Parthenon temple were so life-like it appeared the artists had turned stone into flesh.

Their work has rarely been bettered – the techniques used were largely forgotten until they were revived in the Renaissance when artists carved statues in the Ancient Greek style, most notably Michelangelo’s David.

Dr Li Xiuzhen, senior archaeologist at the tomb’s museum, agreed that it appeared Ancient Greece had influenced events in China more than 7,000km.

“We now have evidence that close contact existed between the First Emperor’s China and the West before the formal opening of the Silk Road,†the expert said.

“This is far earlier than we formerly thought.

RTWT

06 Aug 2018

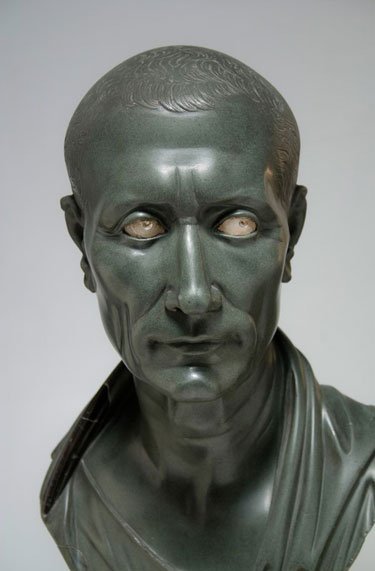

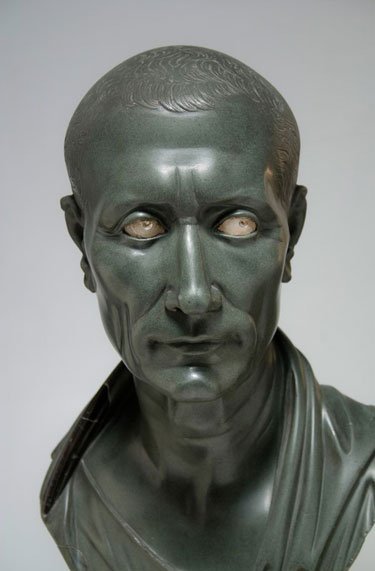

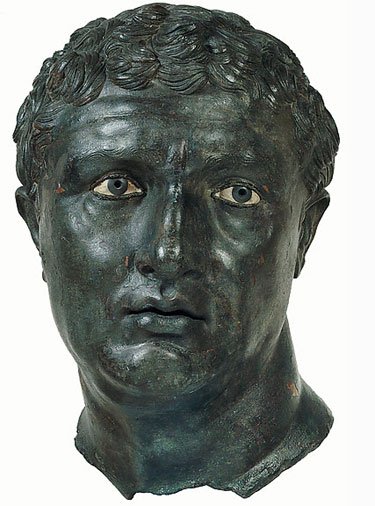

Bust of Julius Caesar. Romano-Egyptian, ca. 100s BC. Green basalt, 17 5/16 × 10 ¼ × 9 13/16 in. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

Doesn’t he look wily?

04 Oct 2016

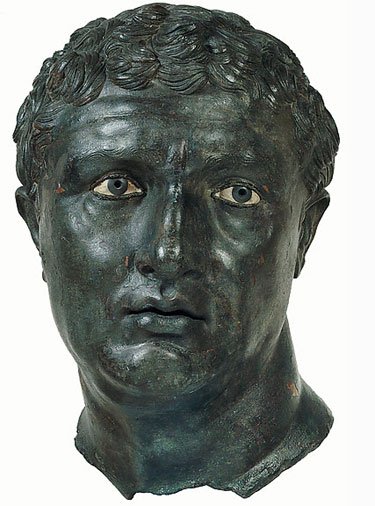

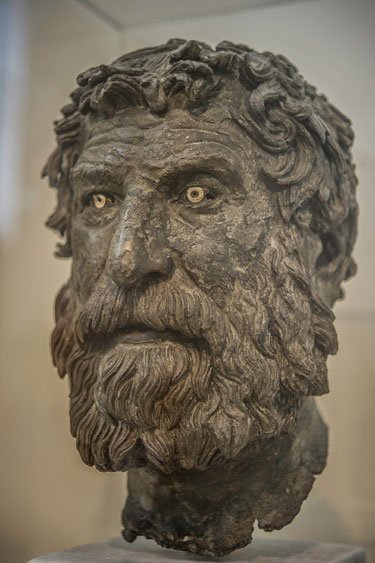

Bronze Head of Seuthes III, ruler of the Odrysian kingdom of Thrace from c. 331 BC to c. 300 BC.

Found in the Golyamata Kosmatka mound, a little over a half a mile south of the town of Shipka, Bulgaria.

13 Jun 2016

Portrait of a Man from Delos, Bronze, c. 100 B.C., National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

G.W. Bowersock (a leading authority on Hellenistic Art), in the New York Review of Books, recommends emulating Turgenev and taking in the Metropolitan Museum’s current Pergamon-Hellenistic Art exhibition.

In January 1880 the great Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev, author of Fathers and Sons and one of the most cosmopolitan Russian writers of the time, was visiting Berlin, when he paid a visit to the Altes Museum. What he saw there not only made a profound impression upon him personally but marked the beginning of a momentous transformation in European understanding of the art and culture of the ancient Mediterranean world. …

Visitors to the Metropolitan Museum’s current exhibition devoted to Pergamon and the Hellenistic kingdoms of antiquity can now recapture Turgenev’s excitement and exaltation, even though what is on display inevitably corresponds only in part to what he saw. Almost all the reliefs in 1880 had arrived in Berlin within the previous two years, after the opening of German excavations at the site in 1878. Over the decades that followed they were incorporated into a reconstruction of the Pergamon altar that has long been one of the glories of the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

That museum is currently undergoing renovation, and this has allowed many of its objects, though obviously not the altar itself or most of the reliefs, to be lent to New York. The reliefs in New York are panels that show the birth and infancy of Heracles’ son Telephus, who was the mythical founder of the city. The Telephus reliefs come from the inner walls of the colonnade at the top of the altar, and so the Gigantomachy frieze has to be appreciated through photographs. But the curators of the exhibition have successfully combined the loans from Berlin with major pieces from many other collections so as to provide a wide-ranging exploration of the art and culture of the so-called Hellenistic world. This is the international milieu in which Pergamon shone brightly and to which Rome was much indebted.

Hellenistic culture is often misunderstood and confused with Hellenic (or Greek) culture. Yet it is very different, though related. It is a culture that derives from the conquests of Alexander the Great, who, under the inspiration of his teacher Aristotle, brought the legacy of classical Greece across Asia Minor, the Middle East, and India. The Metropolitan Museum has not only created a visual effect that would inspire a modern Turgenev, but it has given Hellenistic art, which lies between the art of classical Greece and that of Rome, the prominence it amply deserves.

Photos of Objects Being Exhibited

Exhibition catalog (cheaper at Amazon): Pergamon and the Hellenistic Kingdoms of the Ancient World

21 Nov 2015

A Greek Late Archaic- maybe Etruscan – Bronze male siren.

Who knew that there were male sirens?

via Belacqui.

12 Nov 2015

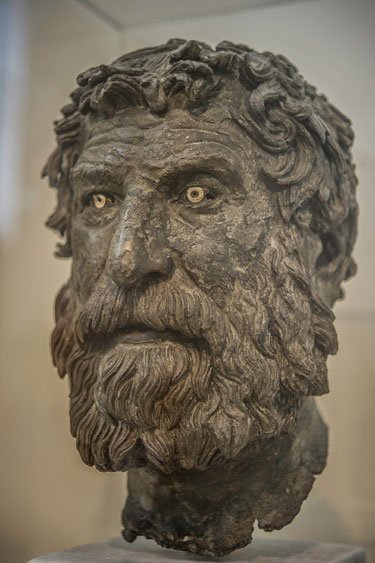

Bronze portrait of a philosopher recovered from the Antikythera shipwreck (crafted circa 240 BC)

Am I mistaken, or did somebody insert a pair of cartridge bases for the eyes?

23 Nov 2013

Dancing Satyr of Mazara del Vallo, fourth-century B.C., Greece

Wikipedia:

The over-lifesize Dancing Satyr of Mazara del Vallo is a Greek bronze statue, whose refinement and rapprochement with the manner of Praxiteles has made it a subject of discussion.

Though the satyr is missing both arms, one leg and its separately-cast tail (originally fixed in a surviving hole at the base of the spine), its head and torso are remarkably well-preserved despite millennia spent at the bottom of the sea. The satyr is depicted in mid-leap, head thrown back ecstatically and back arched, his hair swinging with the movement of his head. The facture is highly refined; the whites of his eyes are inlays of white alabaster.

Though some have dated it to the 4th century BCE and said it was an original work by Praxiteles or a faithful copy, it is more securely dated either to the Hellenistic period of the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE, or possibly to the “Atticising” phase of Roman taste in the early 2nd century CE. A high percentage of lead in the bronze alloy suggests its being made in Rome itself.

The torso was recovered from the sandy sea floor at a depth of 500 m (1600 ft.) off the southwestern coast of Sicily, on the night of March 4, 1998, in the nets of the same fishing boat (operating from Mazara del Vallo, hence the sculpture’s name) that had in the previous year recovered the sculpture’s left leg. …

Restoration at the Istituto Centrale per il Restauro, Rome, included a steel armature so that the statue can be displayed upright. … [I]t is on permanent display in the Museo del Satiro in the church of Sant’Egidio.

Via Ratak Monodosico.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Hellenistic Art' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|