Category Archive 'Jim Corbett'

06 Aug 2022

In the London Spectator, Neil Clark defies contemporary political correctness by recommending the classic hunting books of maneater-eliminator par excellence Jim Corbett.

I was reminded of Corbett and his wonderful books when reading last week that human-assaulting tigers are once again on the prowl in Nepal, with 104 attacks and 62 people killed in the past three years. Conservation efforts have seen tiger numbers rise three-fold since 2010, but with that good news comes the bad news of increased danger to humans. In March a tiger believed to have killed five people was captured in western Nepal. Meanwhile in India, a tigress apparently responsible for two deaths was captured in June.

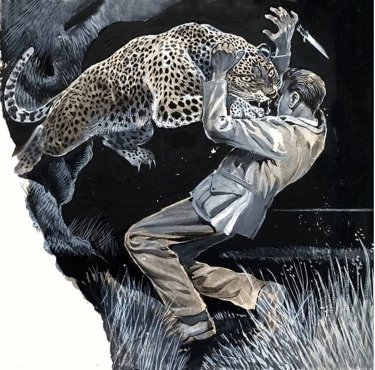

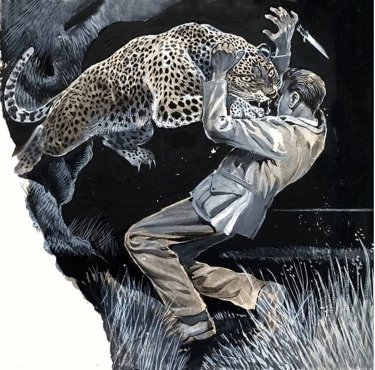

So the man-eaters are back, though the terror from the current wave does thankfully seem less than in the days of Corbett. ‘No curfew order has ever been more strictly enforced, and more implicitly obeyed, than the curfew imposed by the man-eating leopard of Rudraprayag,’ he wrote. During the hours of daylight, life continued more or less as normal. But at night, ‘an ominous silence brooded over the whole area’. Little wonder. For eight long years, between 1918 and 1926, the 50,000 inhabitants of Garhwal in the United Provinces of northern India, and the 60,000 Hindu pilgrims who passed through the district annually on their way to the ancient shrines at Kedarnath and Badrinath, lived in fear of the ferocious big cat that claimed the lives of 125 people.

One of the victims was a 14-year-old orphan employed to look after a flock of 40 goats. He slept with the goats in a small room. But even though the door was fastened by a piece of wood, the leopard got in, killed the poor boy and then carried him off to a deep, rocky ravine where he devoured him. The goats were left completely unscathed. A shocking story, and there are plenty more like it, but don’t worry – we can be sure that our hero Jim will ultimately stop the leopard’s reign of terror.

I first encountered Corbett’s three-volume Man-Eater series in childhood. We had copies of his books in my school library back in the mid-1970s and they were always among the most popular to borrow.

Goodness me, how those hardback editions with their pictures of snarling big cats on the cover captured our imaginations and broadened our horizons. Corbett was a great writer – ‘dramatic yet reflective’ to quote the OUP’s omnibus edition of his works – who brought the Indian Himalayas of the early 20th century vividly to life with his understated, descriptive prose.

For much of the post-war era his books on hunting the man-eating Bengal tigers and leopards of the Raj were hugely successful. More than four million copies of Man-Eaters of Kumaon had been sold worldwide by 1980. The BBC made a television version six years later. But one worries that in the 21st century, Corbett’s work is not read anything like so widely, particularly by children who would gain so much from his incredibly exciting tales.

Yes, the books involve hunting, which is now very un-PC – but it’s the hunting of bloodthirsty beasts which had claimed more than 1,500 lives between them. And aside from that, there is so much we can learn about life from Corbett’s writing.

RTWT

Jim Corbett’s accounts of tracking down man-eating leopards and tigers have some pretty scary moments. I remember one scene in which Corbett is bending down in a gully examining the pugmarks of the tiger he is tracking and bits of dirt begin falling on his head. Corbett was not the only one hunting, it turns out, and his adversary is right above him.

Amazon’s Jim Corbett page.

05 Mar 2019

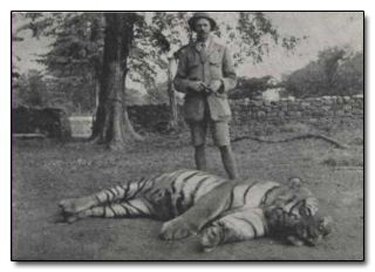

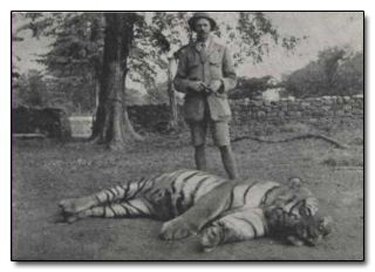

Jim Corbett with the Champawat tiger.

Leave it to the current generation of pseudo-intelligentsia. They can screw up anything. Dane Huckelbridge, for instance, takes one chapter of the great Jim Corbett’s Big Game Hunting classic Maneaters of Kumaon (1944), and makes his own book out of it, No Beast So Fierce: The Terrifying True Story of the Champawat Tiger, the Deadliest Animal in History (2019).

The difference between Jim Corbett writing a first-hand account in the 1940s and Dane Huckelbridge recycling that account today is the ideology. Jim Corbett’s story is a modest, downright self-effacing account of how a local sportsman went to the assistance of terrified Indian villagers and tracked down and killed an extraordinarily bold and aggressive man-eating tigress who’d killed and eaten a record 436 people. Corbett does attribute the tiger’s human predation to a jaw injury from an old bullet-wound, but Corbett tells a stoic and under-stated modern version of the classic man versus monster story.

For Huckelbridge though, the man versus monster saga is just a secondary problem arising from a more basic, more important conflict: British Colonialism versus Pristine Native India.

Then there is Jim Corbett, the now-legendary hunter who was finally commissioned by the British government to end the Champawat Tiger’s reign. To many, even in present-day India, he is nothing short of a secular saint, a brave and selfless figure who risked life and limb to defend poor villagers when no one else would. To others, particularly academics engaged with post-colonial ecologies, he is just another perpetrator of the Eurocentric paternalism that defined the colonial experience. Each is a fair judgment. …

Which brings us, inevitably, to colonialism itself—a topic far too broad and multifaceted for any single book, let alone one that’s concerned primarily with man-eating tigers. Yet it is colonialism, undeniably, and the onslaught of environmental destruction that it almost universally heralds, that served as the primary catalyst in the creation of our man-eater. It may have been a poacher’s bullet in Nepal that first turned the Champawat Tiger upon our kind, but it was a full century of disastrous ecological mismanagement in the Indian subcontinent that drove it out of the wild forests and grasslands it should have called home, and allowed it to become the prodigious killer that it was.

What becomes clear upon closer historical examination is that the Champawat was not an incident of nature gone awry—it was in fact a man-made disaster. From Valmik Thapar to Jim Corbett himself, any tiger wallah could tell you the various factors that can turn a normal tiger into a man-eater: a disabling wound or infirmity, a loss of prey species, or a degradation of natural habitat. In the case of the Champawat, however, we find not just one but all three of these factors to be irrefutably present. Essentially, by the late nineteenth century, the British in the United Provinces of northern India and their Rana dynasty counterparts in western Nepal had created, through a combination of irresponsible forestry tactics, agricultural policies, and hunting practices, the ideal conditions for an ecological catastrophe.

And it was the sort of catastrophe we can still find whiffs of today, be it in the recent spate of shark attacks in Réunion Island, the rise of human–wolf conflict on the outskirts of Yellowstone, or even the man-eating tigers that continue to appear in places like the Sundarbans forest of India or Nepal’s Chitwan National Park. In the modern day, we have at last, thankfully, come to realize the importance of apex predators in maintaining the health of our ecosystems—but we’re still negotiating, somewhat painfully, how best to live alongside them. And that’s to say nothing of the far more sweeping problems posed by global warming and mass extinction, exigencies that have arisen from very much the same amalgamation of economic mismanagement and environmental destruction. Apex predators are generally considered bellwethers of the overall health of the environment, and at present, with carbon emissions on the rise and natural habitats diminishing, the outlook for both feels disarmingly uncertain.

Which is why this particular story of environmental conflict is not only relevant, but urgent and necessary. At its core, Jim Corbett’s quest to rid the valleys of Kumaon of the Champawat Tiger is dramatic and straightforward, but the tensions that underscore it contain the resonance of much larger and more grievous issues. Yes, it is a timeless tale of cunning and courage, but also a lesson, still very much pertinent today, about how deforestation, industrialization, and colonization can upset the fragile balance of cultures and ecosystems alike, creating unseen pressures that, at a certain point, must find their release.

What a spectacular mélange of politically correct, fashionable think nonsense!

All of Mr. Huckelbridge’s pious notions about “ecosystems” healthy or otherwise, “apex predators,” proper forestry, suitable hunting practices, game conservation,and Environmentalism are entirely Western ideas. When he applies them to Kumaon, he himself is being colonialist.

The Champawat maneater was undoubtedly injured by an unskilled native poacher armed with a primitive musket, shooting at a tiger in defiance of hunting laws and game permits invented and imposed by the British Raj. How Huckelbridge can claim that this occurred because the poor tiger was driven out of some unidentified “forests and grasslands” by “a century of ecological mismanagement and environmental destruction” to arrive at the forests and grasslands of Kumaon is unexplained. Where exactly was it that all this alleged mismanagement and destruction occurred? Were there no native tigers in Kumaon previous to all this nearby mismanagement and destruction? What exactly does Huckelbridge think the British (and their Rana dynasty of Western Nepal counterparts) mismanaged and destroyed? Why are the British supposedly to blame for (politically independent) Nepalese actions and policies anyway?

It’s all just a farrago of Enviro-sanctimony and cant lavishly seasoned with the usual “British Colonialism was simply awful” left-wing fantasy.

In reality, the difference between Pre-Raj India and the India of Jim Corbett was that, in the former, tigers undoubtedly had more commonly the upper hand, most humans were unarmed or poorly armed, maneaters munched their way through the Indian peasantry unrebuked without records or scores of the numbers eaten ever being known or kept.

Huckelbridge’s book is nothing more than a breathless re-telling of one chapter of Maneaters of Kumaon accompanied by a truckload of PC nonsense and a lot sanctimonious self-righteousness. Consign this one to Kali!

21 Jan 2015

Jim Corbett’s the best quality boxlock W.J. Jeffery & Co. .450-400 double rifle, with which he killed so many man-eating tigers for the Indian government (Elmer Keith Estate Coll.).

Jim Corbett described using that .450/400 Jeffrey to slay the Thak Man-Eater at about 6:00pm on November 30, 1938, in “Man-Eaters of Kumaon”:

The tigress was now so close that I could hear the intake of her breath each time before she called, and as she again filled her lungs, I did the same with mine, and we called simultaneously. The effect was startingly instantaneous. Without a second’s hesitation she came tramping and then she stepped right out into the open, and, looking into my face, stopped dead. Owing to the nearness of the tigress, and the fading light, all that I could see of her was her head. My first bullet caught her under the right eye and the second, fired more by accident than with intent, took her in the throat and she came to rest with her nose against the rock. The recoil from the right barrel loosened my hold on the rock and knocked me off the ledge, and the recoil from the left barrel, fired while I was in the air, brought the rifle up in violent contact with my jaw and sent me heels over head right on top of the men and goats. Once again I take my hat off to those four men for, not knowing but what the tigress was going to land on them next, they caught me as I fell and saved me from injury and my rifle from being broken.â€

This was the last man-eater killed by Corbett.

—————————-

Elmer Keith died in 1984 and now, thirty years later, the famous writer’s personal firearms collection is finally appearing for sale in James D. Julia’s March 15th, 16th & 17th Firearms Auction.

Not many of us will be able to afford to own any of the highlights of the Keith Collection, but it’s certainly worth looking at the on-line catalog and imagining what you’d do if you won the Irish Sweepstakes in time to bid.

Here are two examples, either of which would be very difficult to top for historical significance and associations.

Hamilton Bowen will build you an unengraved replica (on a Ruger action) of Elmer Keith’s No. 5 .44 Special SA for a mere $4495.00. How high can the original possibly go? Six figures would not surprise me.

————————————–

“The most influential custom handgun ever made!” Elmer Keith’s own No. 5 Colt SA in .44 Special built in 1927 as “the last word in sixguns.”

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Jim Corbett' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|