Category Archive 'Metropolitan Museum of Art'

05 Aug 2024

The Metropolitan Museum describes this wonderful object thusly:

Title: Aquamanile in the Form of a Crowned Centaur Fighting a Dragon

Date: 1200–1225

Geography: Made in possibly Hildesheim, Lower Saxony, Germany

Culture: German

Medium: Copper alloy

Dimensions: Overall: 14 3/8 x 13 3/4 x 5 in., 8.347lb. (36.5 x 34.3 x 12.7 cm, 3786g)

Overall PD: 14 3/8 (at front feet) x 5 x 13 3/4 in. (36.5 (at front feet) x 12.7 x 35 cm)

Classification: Metalwork-Copper alloy

Credit Line: Rogers Fund, 1910

Accession Number: 10.37.2

————————————

Important to know:

An aquamanile is a jug or ewer used to pour water for the washing of hands over a basin.

————————————

But the description is wrong. In reality, it is King Pellinore riding, or merely combined with, Glatisant, the Questing Beast, who has the head of a snake, the body of a leopard, the haunches of a lion (lacking here), and the feet of a hart, from the Medieval Arthurian stories.

19 Sep 2017

Sickle sword

Period:

Middle Assyrian

Date:

ca. 1307–1275 B.C.

Geography:

Northern Mesopotamia

Culture:

Assyrian

Medium:

Bronze

Dimensions:

L. 54.3 cm

Classification:

Metalwork-Implements-Inscribed

Credit Line:

Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1911

Accession Number:

11.166.1

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 406

This curved sword bears the cuneiform inscription “Palace of Adad-nirari, king of the universe, son of Arik-den-ili, king of Assyria, son of Enlil-nirari, king of Assyria,” indicating that it was the property of the Middle Assyrian king Adad-nirari I (r. 1307–1275 B.C.). The inscription appears in three places on the sword: on both sides of the blade and along its (noncutting) edge. Also on both sides of the blade is an engraving of an antelope reclining on some sort of platform.

Curved swords appear frequently in Mesopotamian art as symbols of authority, often in the hands of gods and kings. It is therefore likely that this sword was used by Adad-nirari, not necessarily in battle, but in ceremonies as an emblem of his royal power.

13 Jun 2016

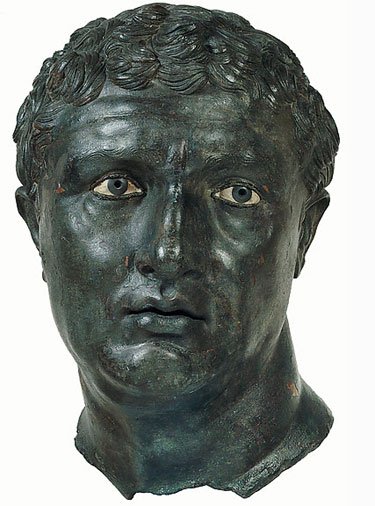

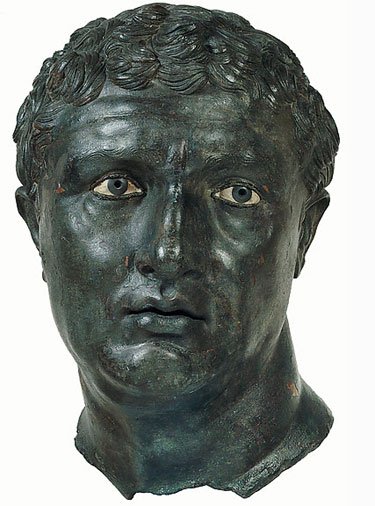

Portrait of a Man from Delos, Bronze, c. 100 B.C., National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

G.W. Bowersock (a leading authority on Hellenistic Art), in the New York Review of Books, recommends emulating Turgenev and taking in the Metropolitan Museum’s current Pergamon-Hellenistic Art exhibition.

In January 1880 the great Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev, author of Fathers and Sons and one of the most cosmopolitan Russian writers of the time, was visiting Berlin, when he paid a visit to the Altes Museum. What he saw there not only made a profound impression upon him personally but marked the beginning of a momentous transformation in European understanding of the art and culture of the ancient Mediterranean world. …

Visitors to the Metropolitan Museum’s current exhibition devoted to Pergamon and the Hellenistic kingdoms of antiquity can now recapture Turgenev’s excitement and exaltation, even though what is on display inevitably corresponds only in part to what he saw. Almost all the reliefs in 1880 had arrived in Berlin within the previous two years, after the opening of German excavations at the site in 1878. Over the decades that followed they were incorporated into a reconstruction of the Pergamon altar that has long been one of the glories of the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

That museum is currently undergoing renovation, and this has allowed many of its objects, though obviously not the altar itself or most of the reliefs, to be lent to New York. The reliefs in New York are panels that show the birth and infancy of Heracles’ son Telephus, who was the mythical founder of the city. The Telephus reliefs come from the inner walls of the colonnade at the top of the altar, and so the Gigantomachy frieze has to be appreciated through photographs. But the curators of the exhibition have successfully combined the loans from Berlin with major pieces from many other collections so as to provide a wide-ranging exploration of the art and culture of the so-called Hellenistic world. This is the international milieu in which Pergamon shone brightly and to which Rome was much indebted.

Hellenistic culture is often misunderstood and confused with Hellenic (or Greek) culture. Yet it is very different, though related. It is a culture that derives from the conquests of Alexander the Great, who, under the inspiration of his teacher Aristotle, brought the legacy of classical Greece across Asia Minor, the Middle East, and India. The Metropolitan Museum has not only created a visual effect that would inspire a modern Turgenev, but it has given Hellenistic art, which lies between the art of classical Greece and that of Rome, the prominence it amply deserves.

Photos of Objects Being Exhibited

Exhibition catalog (cheaper at Amazon): Pergamon and the Hellenistic Kingdoms of the Ancient World

30 Jan 2015

Ennion, mold-blown glass cups (1st century A.D)

From the Metropolitan Museum via Belacqui.

11 Jan 2010

The courage of the elite: Metropolitan Museum prudentially removes images of Mohammed and renames Islamic Galleries.

———————————————————-

High rise buildings in Mecca make it evident that roughly 200 mosques are pointing in the wrong direction.

———————————————————-

Crime pays in Norway.. Foreigners qualify for welfare after a year in jail. If they serve three years, they get health benefits and qualify for old age pension. Hat tip to the News Junkie.

———————————————————-

Lawsuit begins in California federal court contending that the US Constitution mandates Gay Marriage. Wouldn’t Gouverneur Morris be surprised?

———————————————————-

Obama postpones State of the Union address in order to avoid preempting season opener of Lost.

15 Nov 2007

A copy of Bashford Dean’s Catalogue of European Court Swords and Hunting Swords including the Ellis, De Dingo, Riggs and Reubell collections, published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1929 would probably cost you more than $500, if you could find a copy for sale. This web-site offers a complete scan of the entire catalogue.

Bashford Dean:

It is fair to say that court swords, which came into vogue during the second half of the seventeenth century, were of extraordinary merit as objects of art. They were beautiful in lines, rich and varied in ornament, designed by distinguished painters, engravers, and medallists; they furnished even a brilliant point of interest in the court circle of baroque times – giving the final touch to the personal equipment of the courtiers of the Louis in France, of the pretentious nobles who thronged Italian palaces, of the ceremonious magnates of Germany and Poland, or of the wealthy lords and commoners of England. In fact, there can be no question that as an object of personal adornment a sword of the richest type occupied a high place in the minds of many personages of those days; we have only to examine their state portraits to be convinced that this “side-arm was receiving great attention as an object of beauty. We may even infer that many a seigneur who sat for his portrait was as keenly interested in recording for posterity the details of his sword hilt as the features of his face. …

Hunting, which formed no small part of the social life of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, developed épées de chasse, couteaux, and coutelas, which were in keeping with the rich hunting costume and with the dress sword. They were short, carried from a hunting belt, and while they were often provided with guard, quillons, and knuckle guard, they never had the pas d’âne, since this was a structure belonging only to fencing (see fig. 7, which indicates types A and B). In a word, they represent decadent swords, small enough to be conveniently carried in the forest, to be used on very rare occasions to defend the wearer (very ineffectively) from enraged boar or stag, daintily to bleed the game, but never to function in butchery. The art of chopping up the animal – maitrise de veneur of the preceding century, of the days of Maximilian, Charles V, Henry VIII, Francis I – now belonged only to the court butcher and his attendants. Hunting knives (1) stand therefore on another line of descent; they developed from knives, becoming heavier, broader, more specialized. Hunting swords, on the other hand, are degenerate court swords, which by loss of structures attain nearly the condition of glorified knives. Hence it follows that the older hunting swords resemble more closely the short-sword of the period; while the later hunting swords are knife-like. But even here, where the blade becomes single-edged, it is still slender, pointed at tip, and its hilt ever bears the quillons of a sword; its scabbard as well is that of a sword with similar mounts. In style and ornament it still retains close kinship with the court sword – which was apt to replace it so soon as the owner changed his costume.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Metropolitan Museum of Art' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|