Category Archive 'Noam Chomsky'

20 Apr 2016

That skunk Heidegger

From Scientific Philospher (who mentions 30, but only list 10 and offers no link, but I found them at Flavorwire).

Bertrand Russell on Aristotle

“I do not agree with Plato, but if anything could make me do so, it would be Aristotle’s arguments against him.â€

Jean-Paul Sartre on Albert Camus

“Camus… a mix of melancholy, conceit and vulnerability on your part has always deterred people from telling you unvarnished truths. The result is that you have fallen prey to a gloomy immoderation that conceals your inner difficulties and which you refer to, I believe, as Mediterranean moderation. Sooner or later, someone would have told you this, so it might as well be me.â€

Camille Paglia on Michel Foucault

“The truth is that Foucault knew very little about anything before the seventeenth century and, in the modern world, outside France. His familiarity with the literature and art of any period was negligible. His hostility to psychology made him incompetent to deal with sexuality, his own or anybody else’s. … The more you know, the less you are impressed by Foucault.†…

Bertrand Russell on Georg Hegel

“Hegel’s philosophy is so odd that one would not have expected him to be able to get sane men to accept it, but he did. He set it out with so much obscurity that people thought it must be profound. It can quite easily be expounded lucidly in words of one syllable, but then its absurdity becomes obvious.â€

Noam Chomsky on Slavoj Žižek

“There’s no ‘theory’ in any of this stuff, not in the sense of theory that anyone is familiar with in the sciences or any other serious field. Try to find… some principles from which you can deduce conclusions, empirically testable propositions where it all goes beyond the level of something you can explain in five minutes to a 12-year-old. See if you can find that when the fancy words are decoded. I can’t. So I’m not interested in that kind of posturing. Žižek is an extreme example of it. I don’t see anything to what he’s saying.â€

Slavoj Žižek on Noam Chomsky

“Well, with all deep respect that I do have for Chomsky, my… point is that Chomsky, who always emphasizes how one has to be empirical, accurate… well, I don’t think I know a guy who was so often empirically wrong.â€

Karl Popper on Ludwig Wittgenstein

“Not to threaten visiting lecturers with pokers.†(On being challenged by a poker-wielding Wittgenstein to produce an example of a moral rule; the discussion degenerated quickly from there.)

Karl Popper on Martin Heidegger

“I appeal to the philosophers of all countries to unite and never again mention Heidegger or talk to another philosopher who defends Heidegger. This man was a devil. I mean, he behaved like a devil to his beloved teacher, and he has a devilish influence on Germany… One has to read Heidegger in the original to see what a swindler he was.â€

Arthur Schopenhauer on Georg Hegel

“Hegel, installed from above, by the powers that be, as the certified Great Philosopher, was a flat-headed, insipid, nauseating, illiterate charlatan who reached the pinnacle of audacity in scribbling together and dishing up the craziest mystifying nonsense.â€

17 Jan 2013

Aaron Swartz (November 8, 1986 – January 11, 2013)

Argues the learned and cynical

Mencius Moldbug, and he makes a darned good case.

Aaron, born one of humanity’s natural nobles, grows up in a century cleansed by military force of its own cultural heritage, in which all surviving noble ideals are leftist ideals. No one ever had a chance to tell him that his only honorable option was to live in the past. And in any case, that option was probably too antisocial even for Aaron Swartz. He must be noble, he cannot retreat to mere selfish bourgeois money-grubbing and family-rearing. So he must be an activist.

So he takes the blue pill. He starts with a blue joint or two and gradually works his way up to the blue heroin. He believes in his century’s narrative as it is – except more so. Why not more so? For even without marinating his brain in Chomsky, what bright young person can miss all the trouble our polity has in living up to its own comm – I mean, “progressive” – ideals?

The Nazis are beaten, supposedly. But somehow the seeds of autocracy are everywhere. Wherever you see a corporation, you see a little Third Reich with its own pompous CEO-fuehrer. Wherever you see property, especially inherited property (have you noticed the increasingly universal meme of saying “privilege” when you mean “property?”), you see a little king of a little kingdom, whose answer to “why do you own this” is no more than “because I do.”

As an Aaron Swartz bred on Horace instead of John Dewey might have remarked, tamen usque recurret [Naturam expellas furca, tamen usque recurret. “You may drive out Nature with a pitchfork, yet she still will hurry back.” Book I, epistle x, line 24 -DZ]. Of course the utopia is unachievable. As a geek world which had not Chomsky but Mosca on its dogeared hackerspace bookshelves would know in its bones, autocracy is universal and cannot be repealed, only concealed. Always and everywhere, strong minorities rule weak majorities.

You cannot drive out nature with a pitchfork. …

Here’s how Chomsky kills: first, he sets you to the pitchfork. In the Plato’s cave of Chomsky it is not nature, of course, that you are driving out with a pitchfork. It is black, unnatural, fascist conspiracy. Which is naturally everywhere – and yet, everywhere in embryo. Giant terrifying kings and dictators are nowhere to be hacked and sawn. It was your ancestors who had this privilege. Today, in a diminished age, the enemy is no more than the seeds and sprouts of advancing black reaction, whose every great stump is crowned with dangerous suckers.

And while these seedlings are everywhere, each is small and weak. Individually, they yield quite handily to the hoe, giving the stalwart farmer a sense of progress and victory. If only a local sense. For the activist who is only really interested in power, this is quite enough. He just wants to be part of something that’s fighting something else. It’s a normal human drive. And of course, his team is the winning team, which he likes quite well.

You can be this farmer, and live a happy, successful and fulfilling life. But be sure to focus on the seedlings. Or the old dead stumps. Notice, however, that the vines which slew those old trees have grown so great and woody that they almost resemble trees themselves… and you are in for a different experience. At the very least, you’ll need to come back with something sharper than a pitchfork.

The truth is that the weapons of “activism” are not weapons which the weak can use against the strong. They are weapons the strong can use against the weak. When the weak try to use them against the strong, the outcome is… well… suicidal.

Who was stronger – Dr. King, or Bull Connor? Well, we have a pretty good test for who was stronger. Who won? In the real story, overdogs win. Who had the full force of the world’s strongest government on his side? Who had a small-town police force staffed with backward hicks? In the real story, overdogs win.

“Civil disobedience” is no more than a way for the overdog to say to the underdog: I am so strong that you cannot enforce your “laws” upon me. I am strong and might makes right – I give you the law, not you me. Don’t think the losing party in this conflict didn’t try its own “civil disobedience.” And even its own “active measures.” Which availed them – what? Quod licet Jovi, non licet bovi [“What is lawful for Jove is not lawful for cattle.” -JDZ].

In the real world in which we live, the weak had better know their own weakness. If they would gather their strength, do it! But without fighting, even “civil disobedience.” To break a law is to fight. Those who fight had better be strong. Those who are not strong, had better not fight.

In this case, you see, Leviathan’s henchmen simply failed to recognize how feeble their adversary was. Today, U.S. attorney for Massachusetts, Carmen M. Ortiz, argued publicly that she and her minions had not done wrong. They merely intended to convict young Aaron and give him a sentence of six months in a minimum security federal facility. Ortiz neglects to mention that part of his sentence would have denied him usage of a computer and access to the Internet for some very substantial period of time, most likely an interval resembling the full-term of his minimized-to-six-months actually served sentence.

Giving up one’s personal computer and the Internet would not be a life-shattering catastrophe for everyone, but for an IT prodigy, software designer, and Internet activist it would be pretty terrible. It would have been a lot like convicting Mozart of something, putting him in jail for a few months, but also then denying him access to musical performance and composition.

24 Mar 2012

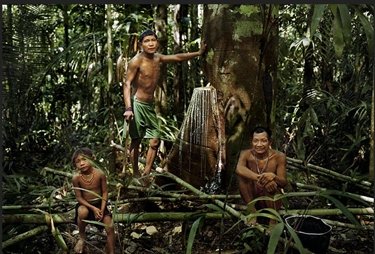

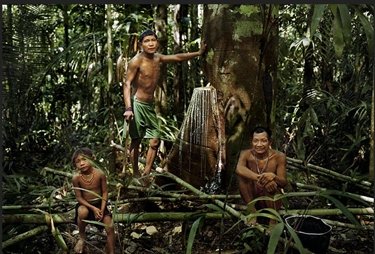

Pirahã

The Chronicle of Higher Education discusses the potentially revolutionary impact on Linguistics of Daniel L. Everett’s new book Language: The Cultural Tool . .

Everett’s study of the Pirahã language offers evidence directly contradicting Noam Chomsky’s regnant belief in a Universal Grammar and taking linguistics back to the thoroughly out-of-fashion Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis which contended that language created the categories by which cognition classifies the world.

Chomsky’s view of linguistics, known as Universal Grammar,… has dominated the field for a half-century.

[Daniel Everett] believes that the structure of language doesn’t spring from the mind but is instead largely formed by culture, and he points to the Amazonian tribe he studied for 30 years as evidence. It’s not that Everett thinks our brains don’t play a role—they obviously do. But he argues that just because we are capable of language does not mean it is necessarily prewired. As he writes in his book: “The discovery that humans are better at building human houses than porpoises tells us nothing about whether the architecture of human houses is innate.”

The language Everett has focused on, Pirahã, is spoken by just a few hundred members of a hunter-gatherer tribe in a remote part of Brazil. Everett got to know the Pirahã in the late 1970s as an American missionary. With his wife and kids, he lived among them for months at a time, learning their language from scratch. He would point to objects and ask their names. He would transcribe words that sounded identical to his ears but had completely different meanings. His progress was maddeningly slow, and he had to deal with the many challenges of jungle living. His story of taking his family, by boat, to get treatment for severe malaria is an epic in itself.

His initial goal was to translate the Bible. He got his Ph.D. in linguistics along the way and, in 1984, spent a year studying at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in an office near Chomsky’s. He was a true-blue Chomskyan then, so much so that his kids grew up thinking Chomsky was more saint than professor. “All they ever heard about was how great Chomsky was,” he says. He was a linguist with a dual focus: studying the Pirahã language and trying to save the Pirahã from hell. The second part, he found, was tough because the Pirahã are rooted in the present. They don’t discuss the future or the distant past. They don’t have a belief in gods or an afterlife. And they have a strong cultural resistance to the influence of outsiders, dubbing all non-Pirahã “crooked heads.” They responded to Everett’s evangelism with indifference or ridicule.

As he puts it now, the Pirahã weren’t lost, and therefore they had no interest in being saved. They are a happy people. Living in the present has been an excellent strategy, and their lack of faith in the divine has not hindered them. Everett came to convert them, but over many years found that his own belief in God had melted away.

So did his belief in Chomsky, albeit for different reasons. The Pirahã language is remarkable in many respects. Entire conversations can be whistled, making it easier to communicate in the jungle while hunting. Also, the Pirahã don’t use numbers. They have words for amounts, like a lot or a little, but nothing for five or one hundred. Most significantly, for Everett’s argument, he says their language lacks what linguists call “recursion”—that is, the Pirahã don’t embed phrases in other phrases. They instead speak only in short, simple sentences.

Beyond mere linguistics, the differences in the two theories have powerful implications overflowing into the moral and political question of equality. If certain peoples perceive and understand the world in fundamentally different ways, it is possible that their language and entire culture may not be equal to our own. Their language and culture may fundamentally limit their capabilities, and Imperialism may actually be morally obligatory.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Noam Chomsky' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|