Category Archive 'Silicon Valley'

17 Aug 2017

The Washington Post reports that many of the key companies providing social networking, financial transfer, and even web-site registration have now decided to take it upon themselves to decide just who is, and who is not, worthy of Internet services and access.

Silicon Valley significantly escalated its war on white supremacy this week, choking off the ability of hate groups to raise money online, removing them from Internet search engines, and preventing some sites from registering at all.

The new moves go beyond censoring individual stories or posts. Tech companies such as Google, GoDaddy and PayPal are now reversing their hands-off approach about content supported by their services and making it much more difficult for alt-right organizations to reach mass audiences.

But the actions are also heightening concerns over how tech companies are becoming the arbiters of free speech in America. …

The censorship of hate speech by companies passes constitutional muster, according to First Amendment experts. But they said there is a downside of thrusting corporations into that role.

Silicon Valley firms may be ill-prepared to manage such a large societal responsibility, they added. The companies have limited experience handling these issues. They must answer to shareholders and demonstrate growth in users or profits — weighing in on free speech matters risks alienating large groups of customers across the political spectrum.

These platforms are also so massive — Facebook, for example, counts a third of the world’s population in its monthly user base; GoDaddy hosts and registers 71 million websites — it may actually be impossible for them to enforce their policies consistently.

Still, tech companies are forging ahead. On Wednesday, Facebook said it canceled the page of white nationalist Christopher Cantwell, who was connected to the Charlottesville rally. The company has shut down eight other pages in recent days, citing violations of the company’s hate speech policies. Twitter has suspended several extremist accounts, including @Millennial_Matt, a Nazi-obsessed social media personality.

On Monday, GoDaddy delisted the Daily Stormer, a prominent neo-Nazi site, after its founder celebrated the death of a woman killed in Charlottesville. The Daily Stormer then transferred its registration to Google, which also cut off the site. The site has since retreated to the “dark Web,†making it inaccessible to most Internet users.

PayPal late Tuesday said it would bar nearly three dozen users from accepting donations on its online payment platform following revelations that the company played a key role in raising money for the white supremacist rally.

In a lengthy blog post, PayPal outlined its long-standing policy of not allowing its services to be used to accept payments or donations to organizations that advocate racist views.

You won’t however find any mention of ANTIFA, the CPUSA, or any group on the Left receiving this kind of attention.

RTWT

06 Aug 2017

When they are not saving the planet from the rest of us or enforcing the rights of the transgendered, Silicon Valley moguls drop by Hiroshi in Los Altos to dine on gold-topped Wagyu steak.

Business Insider:

Hiroshi is an unusual restaurant for unusual clientele.

Located in Los Altos, California, the newly opened Japanese restaurant accommodates only eight people per night and has no menus, no windows, and one table. Dinner costs at minimum $395 a head, but it averages between $500 and $600 with beverages and tax. …

Located in a plaza in Los Altos — residents past and present include Sergey Brin, Steve Jobs, and Mark Zuckerberg — Hiroshi looked plain from the outside.

There were no hours posted on the door. A sign read “Open by appointment only.” …

Dim lighting cast a yellowish hue on the dining area, which was nearly swallowed whole by a single wooden table.

It was made from an 800-year-old Japanese keyaki tree. .. [I]t took 10 men and a small crane to lift the table into the restaurant. New walls were constructed around it.

I followed the aroma of meat crackling over an open fire to the kitchen, where I found the chef and owner, Hiroshi Kimura. He arrived at noon to prepare for the evening’s dinner.

On a business trip to the Bay Area in 2016, Kimura surveyed the restaurant scene and decided that few locations served the region’s wealthiest.

He decided the tech elite needed a high-end place to eat. The restaurant’s details — from the privacy shades on the windows to the discreet back entrance — caters to their needs.

Hiroshi accommodates just one seating of up to eight people per night. If a customer’s party has only six people, they must buy out the whole table. Dinner starts at $395 a head, but Biggerstaff said it averages much closer to $500 to $600 with beverages and tax.

Dinner is about 10 courses, and the menu changes daily. One dish, the tonkatsu sandwich, consists of a breaded, deep-fried pork cutlet prepared in a demi-glace.

Kimura and his sous-chef, who has a background in French cuisine, present each dish — like these sÅmen noodles topped with caviar — simply and tastefully.

Kimura specializes in a rare dish. “Since the age of 16, I have spent 40-plus years in pursuit of perfecting the art of wagyu steaks,” he wrote in a statement on the website. …

Wagyu fetches high prices. The American steak purveyor Allen Brothers sells four two-ounce tenderloin medallions for $165 online. Two rib-eye steaks cost a whopping $280.

Hiroshi has whole tenderloins flown in weekly from Japan. A supplier sends them sealed and packed on ice, via FedEx and includes a certificate of authenticity.

Kimura did not reveal much about how his wagyu steak is prepared. But we know he cooks the steaks over a hibachi — a traditional Japanese stove heated by charcoal. …

The wagyu steak is sprinkled with gold flakes and served with white asparagus and a ponzu sauce. “The gold is more for show,” … “It doesn’t really have any flavor.”

The dish arrives on a sheet of thin, fragrant wood, which prevents the sharp cutlery from destroying the plate.

Each guest has a miniature hibachi stove so they can cook their steak longer or reheat it.

RTWT

14 May 2016

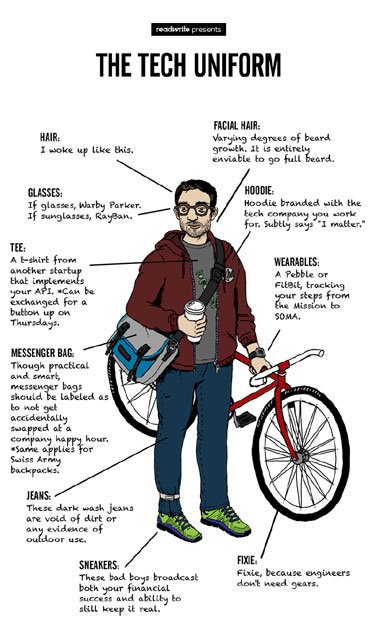

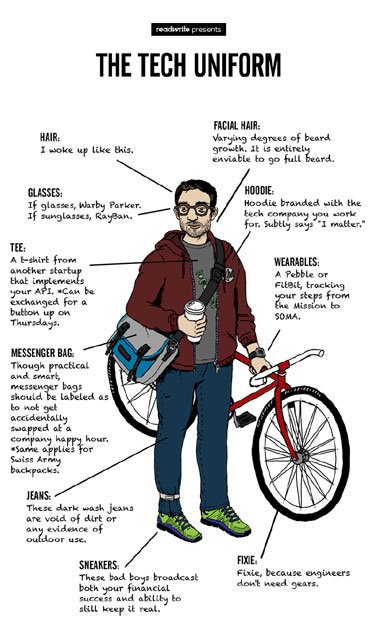

Ulysses768 speculates on why his fellow millennial tech workers are so commonly left-wing politically.

I know there appears to be an easy answer for this question, demographics. Of course they are liberal, you may say. Their workers are mostly young and urban. They reside in Northern California, Boston, and New York. How could they be anything but liberal?

That is true, but they also consist of engineers and highly skilled immigrants. They are people who have worked hard and are well compensated. While many of their peers were “studying†sociology and women’s studies they were taking computer science and engineering courses. What they learned was rooted in logic and the physical world, not rehashed Marxism and utopian fantasies.

When I was growing up in Massachusetts, it made sense that my teachers were predominantly leftist. They belonged to a union and their pay was determined by how well they could scare the town into approving ever increasing school budgets and not by how well they did their jobs. I recall a great anticipation of reaching the working world where market forces would determine success and thus people would see the inherent benefits of individual liberty and classical liberal values.

Since graduating college I’ve been a naval officer, nuclear engineer, software engineer at an older tech company, and now one that is based in the Bay Area. Until now most of my fellow employees have appeared right of center, thus confirming my expectations. That’s not to say it isn’t a great place to work, it most certainly is. However, I am at a total loss to explain its culture or the cultures of other companies of its ilk.

I have a few theories, but I am not very confident in any of them. My definition of “new tech companies†are those that have been created or risen to prominence in the last 15 years, such as Twitter or Facebook.

The people are the same but the companies are more authoritarian. Motivated by a very competitive job market and empowered by financial success, these companies seek to engage with their employees at a new level. They encourage their employees to basically live at work, breaking down the professional and personal divide. This fosters an environment not unlike a university. Everyone must be careful not to offend and the needs of all must be accommodated at the expense of the few. The cultures of victimhood and blind acceptance find fertile soil, and people who disagree learn to keep quiet.

Newer tech companies are more software- and web-based than their predecessors. Therefore aesthetically pleasing design is more important to the success of their products. Therefore more creatives are required and creatives trend left of center.

College indoctrination has become so successful that it has bled into the hard sciences and engineering spaces. My fellow employees seem more liberal because they actually are more liberal.

Read the whole thing.

09 Feb 2014

Samuel Beckett, circa 1970

Mark O’Connell explains, in Slate, how one line buried in one of Samuel Beckett’s obscure modernist works of prose pessimism rather miraculously escaped its confined context to become adopted as a Zen slogan by optimist achievers in Silicon Valley… and on the tennis circuit.

Stanislas Wawrinka’s defeat of Rafael Nadal in the final of the Australian Open last weekend was a milestone not just in the career of a 28-year-old Swiss tennis player but also in the posthumous life of one of the 20th century’s most unswervingly pessimistic writers. This is the first time a Grand Slam title has ever been won by a player with a Samuel Beckett quotation tattooed on his body (barring some unexpected revelation that, say, Ivan Lendl got himself a Waiting for Godot–themed tramp stamp before beating John McEnroe in the 1984 French Open final). The words in question, inked in elaborately curlicued script up the length of Wawrinka’s inner left forearm, are these: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.â€

The quotation is from Worstward Ho, a late, fragmentary prose piece that is one of the most tersely oblique things Beckett ever wrote. But those six disembodied imperatives, from the text’s opening page, have in their strange afterlife as a motivational meme come to much greater prominence than the text itself. The entrepreneurial class has adopted the phrase with particular enthusiasm, as a battle cry for a startup culture in which failure has come to be fetishized, even valorized. Sir Richard Branson, that affable old sage of private enterprise and bikini-based publicity shoots, has advocated from on high the benefits of Failing Better. He breaks out the quote near the end of an article about the future of his multinational venture capital conglomerate, telling us with characteristic self-assurance that it comes “from the playwright, Samuel Beckett, but it could just as easily come from the mouth of yours truly.â€

Hat tips to Steve Bodio and the Dish.

Wawrinka‘s tattoo.

26 Nov 2013

Atherton, Calfornia

Charlotte Allen, in the Weekly Standard, gives her readers a tour of the dystopian future represented by California’s Silicon Valley where left-wing politics goes hand-in-hand with spectacular inequality. The Tech Company owner lives in Atherton or owns, as the saying goes, “his own hilltop in Portola, while the merely upper-middle-class pay $1,200,000 to live in the sort of despicable ranch house equivalent of what a mailman might own in New Jersey. But they both have Mexican illegals to mow their lawns and paint their fences.

“If you live here, you’ve made it,†David Berkey said to me as I rode shotgun in his car two months ago through the Silicon Valley’s wealth belt. The massive house toward which he was pointing belongs to Sergey Brin, cofounder of Google. With a net worth of $24 billion, Brin is Silicon Valley’s third-richest denizen and the fourteenth-richest man in America, according to Forbes. Berkey was chauffeuring me down Atherton Avenue, a wide, straight, completely tree-lined boulevard nicely bifurcating the city of Atherton (population 7,200), located 29 miles south of San Francisco, boasting no commercial real estate, and with a zip code (94027) that was recently listed by Forbes as America’s most expensive.

You couldn’t really see Brin’s house from the car, though—just a swatch of rooftop, maybe a chimney—because the point of the trees lining Atherton Avenue and nearly every other street in Atherton is to hide the dwellings behind them. Where the screens of trees happen to thin, property owners have constructed high hedges, high wooden fences, and high brick walls, so that when you look down Atherton Avenue from the Santa Cruz Mountains to the west toward the commuter railroad station to the east, you see only the allée of trees—pine, palms, eucalyptus, sycamore, and juniper—shades of gray-green and brown-green shimmering placidly in the early autumn sun. “This is the Champs-Élysées of Atherton,†Berkey explained. The other thing we didn’t see from Berkey’s car is people, except for the occasional driver on the road. …

Berkey himself doesn’t live in Atherton. He can’t afford to. He’s a research fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution, and his wife, Eleanor Lacey, is general counsel at SurveyMonkey, which occupies Facebook’s old startup quarters in downtown Palo Alto. That makes them part of what is known as the “middle class†of Silicon Valley: two-career couples with family incomes in the low-to-mid six-figure-range. They and their two daughters live in neighboring Menlo Park, in what is essentially a modest 1950s tract house, the kind of flat-roofed, three-bedroom, two-bath, sliding-glass-patio-door, under-2,000-square-foot residences, pleasant but not pretentious, that were built en masse well into the 1970s as cheap starter homes, because back then it was conceivable that there could be such a thing as a cheap starter home in the valley. Berkey says his own house is currently valued at $1.2 million.

That’s par for the course. Open on any random day the Daily Post, the throwaway newspaper serving the mid-peninsula, and there will be a full-page ad for a “charming updated contemporary home†in Menlo Park or Palo Alto or Mountain View or Sunnyvale, with its single story, its gravel-topped roof, its living-room picture window, its teensy garden strip running alongside the jutting two-car garage that plugs into the kitchen, its pocket-size but grassy front lawn reminiscent of The Wonder Years—and its 1,216 square feet of living space—all “offered at $949,000.†That’s a bargain for the valley.

Berkey drove us out of Atherton, across El Camino Real, the peninsula’s main commercial highway, and across the railroad tracks past the tiny Atherton station, now part of California’s state-run Caltrain system and a commuter stop only on weekends. We were now in the featureless, nearly treeless, semi-industrial flatlands of Menlo Park stretching eastward to the bay. The demographic change was instant: ¡No se habla inglés! There were suddenly plenty of people on the sidewalks—and nearly every single one of them was Latino. There were suddenly plenty of commercial establishments—ramshackle, brightly painted, graffiti-adorned storefronts with hand-painted business signs mostly in Spanish: “Comida Nicaraguense,†“Restaurante Guatemalteco,†“CarnicerÃa†(pork chops and steaks crudely painted on the walls), “PescaderÃa†(fish and crustaceans crudely painted on the walls), “PanaderÃa,†“Check Cashing,†“Gonzalez Auto Sales,†“Sanchez Jewelry,†“Check Cashing,†“Arturo’s Shoe Repair,†“99¢ and Over,†“Check Cashing.â€

Menlo Park is actually only about 20 percent Hispanic and is unabashedly affluent in its own right, but its Hispanic population concentrated next door to the hedgy scrim of Atherton makes for a startling study in contrasts. No one pretends that the gravel-roofed, shack-size houses in this particular neighborhood are “charming†midcentury modern gems. That would be hard to do, what with the weeds, the peeling paint, the chain-link fences, the chained-up guard dogs, and the front lawns paved over to accommodate multiple vehicles for multiple dwellers. The phrase “the other side of the tracks†has vivid meaning. “Look at the newspaper police blotters, and you’ll see that in Atherton the main reported crime is identity theft,†said Berkey. “Here, it’s break-ins.â€

You can laud this underbelly barrio as vibrant immigrant culture or you can decry it as an instant-slum product of untrammeled illegal border-crossing, but it represents an important fact on the ground: These are the people who earn their livings tending to the needs of the high-tech “creative class†that has made Silicon Valley famous. I could see them on Atherton Avenue, the amanuensis class heading up from Menlo Park in their wee panel trucks and Dodge minivans and their Ford flatbeds fitted out with racks for garden tools among the Bentleys, BMWs, Audis, and Lexuses that are the standard Atherton vehicles. They tend the meticulously clipped lawns, flower beds, hedges, and trees of Atherton (Berkey said that it’s not uncommon for an Atherton sentence to begin, “My arborist .  .  . â€). They clean the houses and the swimming pools, they deliver the catering, they watch the children, and they repair the roofs, the plumbing, the balconies, and the wine cellars of the very affluent and the very busy. You might say that across-the-tracks Menlo Park, along with down-market Latino neighborhoods just like it up and down the peninsula—East Palo Alto, parts of Redwood City, the southern end of San Jose—functions as a kind of oversize servants’ wing. It’s safe to say that almost every hotel maid, restaurant busboy, cashier, janitor, retail stocker, and fast-food worker in the valley is Latino.

Master and servant. Cornucopian wealth for a few tech oligarchs plus relatively steady but relatively low-paying work for their lucky retainers. No middle class, unless the top 5 percent U.S. income bracket counts as middle class. Silicon Valley is a tableau vivant of what many economists and professional futurologists say is the coming fate of America itself, a fate to which Americans, if they can’t embrace it as some futurologists hope, should at least resign themselves.

While I was driving with Berkey around Atherton, Tyler Cowen, economics professor at George Mason University and author of The Great Stagnation (2011), published a new book, Average Is Over: Powering America Beyond the Age of the Great Stagnation. There, Cowen bluntly predicted what he called “wage polarization.†The increasing ability of computers to perform ordinary tasks will inexorably transform America into an income oligarchy in which the top 15 percent of people—with skills “that are a complement to the computerâ€â€”will enjoy “cheery†labor-market prospects and soaring incomes, while the bottom 85 percent, that is to say, 267 million out of America’s 315 million people, will be lucky to find Walmart-level jobs or scrape together marginal “freelance†livings running $25-a-pop errands for their betters via TaskRabbit (say, picking up and delivering a pair of designer shoes from Nordstrom) or renting out their spare bedrooms (if they have any) to overnight lodgers via Airbnb. That is, if they’ll be working at all. “There are many other historical periods, including medieval times, where inequality is high, upward mobility is fairly low, and the social order is fairly stable, even if we as moderns find some aspects of that order objectionable,†Cowen writes in his new book.

In other words, what is coming is the “new feudalism,†a phrase coined by Chapman University urban studies professor Joel Kotkin, a prolific media presence whose New Geography website is an outlet for the trend’s most vocal critics. “It’s a weird Upstairs, Downstairs world in which there’s the gentry, and the role for everybody else is to be their servants,†Kotkin said in a telephone interview. “The agenda of the gentry is to force the working class to live in apartments for the rest of their lives and be serfs. But there’s a weird cognitive dissonance. Everyone who says people ought to be living in apartments actually lives in gigantic houses or has multiple houses.â€

It’s hard to travel anywhere in the valley and not see what Kotkin is talking about.

Read the whole thing.

22 Oct 2013

Silicon Valley

Native Californian Victor Davis Hanson takes a look at the bizarre lifestyle (big money, crappy housing) and even stranger politics of his own state’s technological elite.

Strip away the veneer of Silicon Valley, and it is mostly a paradox. Almost nothing is what it is professed to be. Ostensibly, communities like Menlo Park and Palo Alto are elite enclaves, where power couples can easily make $300,000 to $700,000 a year as mid-level dot.com managers.

But often these 1 percenter communities are façades of sorts. Beneath veneers of high-end living, there are lives of quiet 1-percent desperation. With new federal and California tax hikes, aggregate income-tax rates on dot.commers can easily exceed 50 percent of their gross income. And hip California 1 percenters do not enjoy superb roads and schools or a low-crime state in exchange for forking over half their income.

Housing gobbles much of the rest of their pay. A 1,300-square-foot cottage in Mountain View or Atherton can easily sell for $1.5 million, leaving the owners paying $5,000 to $6,000 on their mortgage and another $1,500 to $2,000 in property taxes each month. Add in the de rigueur Mercedes, BMW, or Lexus and the private-school tuition, and the apparently affluent turn out to have not all that much disposable income. A visitor from Mars might look at their relatively tiny houses, frenzied go-getter lifestyle, and leased BMWs, and deem them no better off materially than middle-class state employees three hours away in supposedly dismal Merced, who earn 20 percent as much, but live in a home twice as large, with only 10 percent of the monthly mortgage and tax costs.

Given exorbitant taxes and housing prices, obviously it is not just the high salaries that draw so many to the San Francisco Bay Area. The “ambiance†of year-round temperate weather, the collective confidence rippling out from new technology, the spinoff from great universities like UC Berkeley and Stanford, and the hip culture of fine eating and entertainment all tend to convince Silicon Valley denizens that they are enviable even though they must work long hours to pay high taxes and to buy tiny and often old homes.

Silicon Valley liberal politics are equally paradoxical, reflect this quiet desperation, and mask hyper-self-interest, old-fashioned rat-race competition, and 21st-century suburban versions of keeping up with the Joneses. The latter may be green, support gay marriage, and oppose restrictions on abortion, but they still are the Joneses of old who define their success by showing off to neighbors what they have, whether high-performance cars or hyper-achieving kids.

In the South Bay counties, Democratic registration outnumbers Republican often 2 to 1. If liberals like Barbara Boxer, Dianne Feinstein, and Nancy Pelosi did not represent the Bay Area, others like them would have to be invented. Yet, most Northern California liberal politics are abstractions that apparently provide some sort of psychological compensation for otherwise living lives that are illiberal to the core.

Read the whole thing.

06 Aug 2010

Antonio, with a Bay area native’s perspective, lists all the reasons why New York City will never be a tech center in a very amusing rant.

Thinking the New York tech scene will ever equal Silicon Valley is as foolish as thinking San Francisco’s puny theater district will one day take on Broadway. Both Silicon Valley and Broadway are unique products of the cities that spawned them, and every attempt to create a Silicon Alley/Silicon Sentier/Skolkovo/whatever in various parts of the world have failed. So far, no one’s managed to do it, and New York sure as hell won’t either. …

$2495 for a 500 sq. ft. one bedroom apartment.

There, that’s how much my first apartment in New York cost (in 2005).

Living in New York, you hemorrhage money, and don’t see much in return. My career salary high-water mark is still working as a quant on Goldman’s credit desk, and I lived worse, from a quality-of-life perspective, than I did as a Berkeley graduate student. ‘Ramen’ money in New York is enough to support three families, and then some, elsewhere. If YCombinator existed in New York, they’d have to dish 5x more than their already slim initial funding to keep new startups in Cheetos for three months.

Basically, startups flourish in the Bay Area the same reason the homeless do: decent weather, relatively cheap living, and no stigma attached to your lifestyle.

Read the whole thing.

13 Jan 2009

Business Week’s Steve Hamm says the problem is greedy investors’ short term thinking and aversion to risk, and those stingy VCs should start funding “bold new directions” while waiting for Uncle Obama to open up the federal tap.

Hamm’s article lit the fuse of Michael S. Malone at Live from Silicon Valley.

Since Steve Hamm and Business Week aren’t willing to give you anything but their own big government/big business solutions to the perceived crisis, let me give you the real story – and real solutions – from somebody who has been on the ground here in Silicon Valley for 45 years:

Yes, Silicon Valley – and by extension, the U.S. high technology industry, is in something of a crisis right now. Part of it is the fact that, as the largest manufacturing sector in the US economy, electronics is not immune to the larger financial crisis currently impacting the world.

But there a lot of other problems as well. For one thing, the venture capital industry is in real trouble – not because of a lack of courage, but because government interference – most notably, Sarbanes-Oxley – has proven almost fatal to the new company creation process. With almost no potential for a big pay-out on the back end (because companies don’t ‘go public’ any more), VC’s are having to be much tighter on the front end. That’s good business, not gutlessness.

As for the entrepreneurs themselves, to charge them with a lack of courage or character is truly insulting. Instead of hob-nobbing with senior executives, Steve should have called me. I would have taken him to the little Peet’s Coffee shop in nearby Cupertino where I get my lattes twice per day. There, I would have shown him that on any given day you can see at least two entrepreneurial teams – a half-dozen guys huddled over a single laptop editing spreadsheets – almost always different, and all dreaming of starting the Next Big Company. There are hundreds of these start-up teams all over the Valley right now – indeed, I think there is more entrepreneurial fervor going on right now than just about any other time in Valley history.

Are these folks thinking small? Are they short on courage? No, what they are is pragmatic. That’s the essence of being an entrepreneur. They know what the business landscape is out there, and they are adjusting their plans to succeed in that new reality.

No, the problem is not that entrepreneurs and investors in Silicon Valley and the rest of high tech aren’t thinking big, it’s that they aren’t being allowed to. If Business Week would just take off its ideological blinders, it would realize that if Washington really wanted to help a sick Silicon Valley, it would get out of the way, and strip away all of those worthless regulations that are inhibiting the imagination and the creativity of this town.

Your are browsing

the Archives of Never Yet Melted in the 'Silicon Valley' Category.

/div>

Feeds

|