Category Archive 'War'

26 May 2025

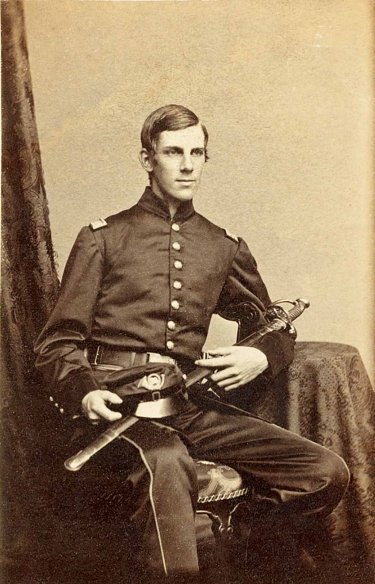

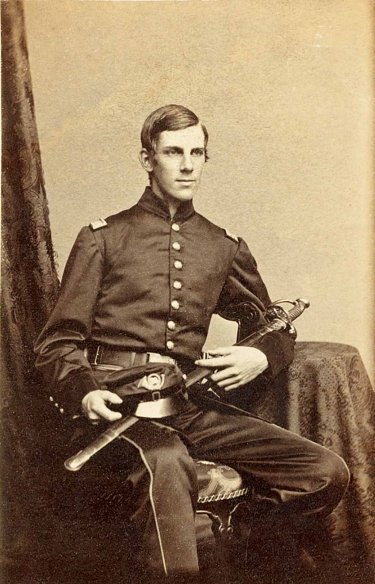

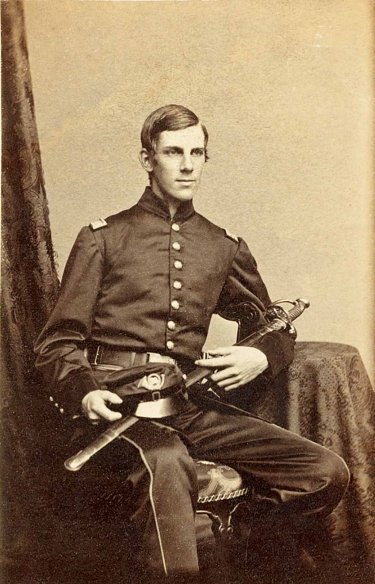

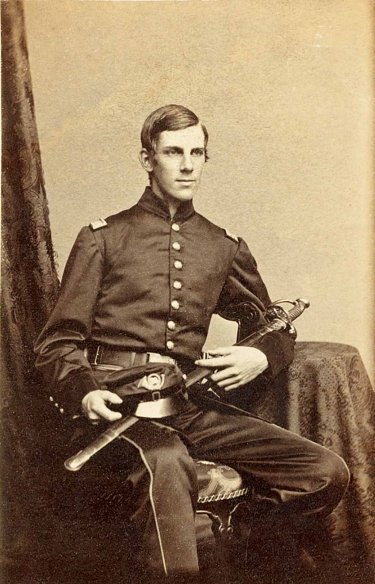

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. was a Second Lieutenant in the 20th Massachusetts Regiment during the Civil War.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. gave a famous speech at Soldiers Field on Memorial Day 1895, in honor of Harvard University’s Civil War dead. It’s a particularly appropriate read at this time of year.

Behind every scheme to make the world over, lies the question: What kind of world do you want? The ideals of the past for men have been drawn from war, as those for women have been drawn from motherhood. For all our prophecies, I doubt if we are ready to give up our inheritance. Who is there who would not like to be thought a gentleman? Yet what has that name been built on but the soldier’s choice of honor rather than life? To be a soldier or descended from soldiers, in time of peace to be ready to give one’s life rather than suffer disgrace, that is what the word has meant; and if we try to claim it at less cost than a splendid carelessness for life, we are trying to steal the good will without the responsibilities of the place. We will not dispute about tastes. The man of the future may want something different. But who of us could endure a world, although cut up into five acre lots, and having no man upon it who was not well fed and well housed, without the divine folly of honor, without the senseless passion for knowledge outreaching the flaming bounds of the possible, without ideals the essence of which is that they can never be achieved? I do not know what is true. I do not know the meaning of the universe. But in the midst of doubt, in the collapse of creeds, there is one thing I do not doubt, that no man who lives in the same world with most of us can doubt, and that is that the faith is true and adorable which leads a soldier to throw away his life in obedience to a blindly accepted duty, in a cause which he little understands, in a plan of campaign of which he has little notion, under tactics of which he does not see the use.

Most men who know battle know the cynic force with which the thoughts of common sense will assail them in times of stress; but they know that in their greatest moments faith has trampled those thoughts underfoot. If you wait in line, suppose on Tremont Street Mall, ordered simply to wait and do nothing, and have watched the enemy bring their guns to bear upon you down a gentle slope like that of Beacon Street, have seen the puff of the firing, have felt the burst of the spherical case-shot as it came toward you, have heard and seen the shrieking fragments go tearing through your company, and have known that the next or the next shot carries your fate; if you have advanced in line and have seen ahead of you the spot you must pass where the rifle bullets are striking; if you have ridden at night at a walk toward the blue line of fire at the dead angle of Spotsylvania, where for twenty-four hours the soldiers were fighting on the two sides of an earthwork, and in the morning the dead and dying lay piled in a row six deep, and as you rode you heard the bullets splashing in the mud and earth about you; if you have been in the picket line at night in a black and unknown wood, have heard the splat of the bullets upon the trees, and as you moved have felt your foot slip upon a dead man’s body; if you have had a blind fierce gallop against the enemy, with your blood up and a pace that left no time for fear—if, in short, as some, I hope many, who hear me, have known, you have known the vicissitudes of terror and triumph in war; you know that there is such a thing as the faith I spoke of. You know your own weakness and are modest; but you know that man has in him that unspeakable somewhat which makes him capable of miracle, able to lift himself by the might of his own soul, unaided, able to face annihilation for a blind belief.

RTWT

26 May 2024

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. was a Second Lieutenant in the 20th Massachusetts Regiment during the Civil War.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. gave a famous speech at Soldiers Field on Memorial Day 1895, in honor of Harvard University’s Civil War dead. It’s a particularly appropriate read at this time of year.

Behind every scheme to make the world over, lies the question: What kind of world do you want? The ideals of the past for men have been drawn from war, as those for women have been drawn from motherhood. For all our prophecies, I doubt if we are ready to give up our inheritance. Who is there who would not like to be thought a gentleman? Yet what has that name been built on but the soldier’s choice of honor rather than life? To be a soldier or descended from soldiers, in time of peace to be ready to give one’s life rather than suffer disgrace, that is what the word has meant; and if we try to claim it at less cost than a splendid carelessness for life, we are trying to steal the good will without the responsibilities of the place. We will not dispute about tastes. The man of the future may want something different. But who of us could endure a world, although cut up into five acre lots, and having no man upon it who was not well fed and well housed, without the divine folly of honor, without the senseless passion for knowledge outreaching the flaming bounds of the possible, without ideals the essence of which is that they can never be achieved? I do not know what is true. I do not know the meaning of the universe. But in the midst of doubt, in the collapse of creeds, there is one thing I do not doubt, that no man who lives in the same world with most of us can doubt, and that is that the faith is true and adorable which leads a soldier to throw away his life in obedience to a blindly accepted duty, in a cause which he little understands, in a plan of campaign of which he has little notion, under tactics of which he does not see the use.

Most men who know battle know the cynic force with which the thoughts of common sense will assail them in times of stress; but they know that in their greatest moments faith has trampled those thoughts underfoot. If you wait in line, suppose on Tremont Street Mall, ordered simply to wait and do nothing, and have watched the enemy bring their guns to bear upon you down a gentle slope like that of Beacon Street, have seen the puff of the firing, have felt the burst of the spherical case-shot as it came toward you, have heard and seen the shrieking fragments go tearing through your company, and have known that the next or the next shot carries your fate; if you have advanced in line and have seen ahead of you the spot you must pass where the rifle bullets are striking; if you have ridden at night at a walk toward the blue line of fire at the dead angle of Spotsylvania, where for twenty-four hours the soldiers were fighting on the two sides of an earthwork, and in the morning the dead and dying lay piled in a row six deep, and as you rode you heard the bullets splashing in the mud and earth about you; if you have been in the picket line at night in a black and unknown wood, have heard the splat of the bullets upon the trees, and as you moved have felt your foot slip upon a dead man’s body; if you have had a blind fierce gallop against the enemy, with your blood up and a pace that left no time for fear—if, in short, as some, I hope many, who hear me, have known, you have known the vicissitudes of terror and triumph in war; you know that there is such a thing as the faith I spoke of. You know your own weakness and are modest; but you know that man has in him that unspeakable somewhat which makes him capable of miracle, able to lift himself by the might of his own soul, unaided, able to face annihilation for a blind belief.

RTWT

30 May 2023

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. was a Second Lieutenant in the 20th Massachusetts Regiment during the Civil War.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. gave a famous speech at Soldiers Field on Memorial Day 1895, in honor of Harvard University’s Civil War dead. It’s a particularly appropriate read at this time of year.

Behind every scheme to make the world over, lies the question: What kind of world do you want? The ideals of the past for men have been drawn from war, as those for women have been drawn from motherhood. For all our prophecies, I doubt if we are ready to give up our inheritance. Who is there who would not like to be thought a gentleman? Yet what has that name been built on but the soldier’s choice of honor rather than life? To be a soldier or descended from soldiers, in time of peace to be ready to give one’s life rather than suffer disgrace, that is what the word has meant; and if we try to claim it at less cost than a splendid carelessness for life, we are trying to steal the good will without the responsibilities of the place. We will not dispute about tastes. The man of the future may want something different. But who of us could endure a world, although cut up into five acre lots, and having no man upon it who was not well fed and well housed, without the divine folly of honor, without the senseless passion for knowledge outreaching the flaming bounds of the possible, without ideals the essence of which is that they can never be achieved? I do not know what is true. I do not know the meaning of the universe. But in the midst of doubt, in the collapse of creeds, there is one thing I do not doubt, that no man who lives in the same world with most of us can doubt, and that is that the faith is true and adorable which leads a soldier to throw away his life in obedience to a blindly accepted duty, in a cause which he little understands, in a plan of campaign of which he has little notion, under tactics of which he does not see the use.

Most men who know battle know the cynic force with which the thoughts of common sense will assail them in times of stress; but they know that in their greatest moments faith has trampled those thoughts underfoot. If you wait in line, suppose on Tremont Street Mall, ordered simply to wait and do nothing, and have watched the enemy bring their guns to bear upon you down a gentle slope like that of Beacon Street, have seen the puff of the firing, have felt the burst of the spherical case-shot as it came toward you, have heard and seen the shrieking fragments go tearing through your company, and have known that the next or the next shot carries your fate; if you have advanced in line and have seen ahead of you the spot you must pass where the rifle bullets are striking; if you have ridden at night at a walk toward the blue line of fire at the dead angle of Spotsylvania, where for twenty-four hours the soldiers were fighting on the two sides of an earthwork, and in the morning the dead and dying lay piled in a row six deep, and as you rode you heard the bullets splashing in the mud and earth about you; if you have been in the picket line at night in a black and unknown wood, have heard the splat of the bullets upon the trees, and as you moved have felt your foot slip upon a dead man’s body; if you have had a blind fierce gallop against the enemy, with your blood up and a pace that left no time for fear—if, in short, as some, I hope many, who hear me, have known, you have known the vicissitudes of terror and triumph in war; you know that there is such a thing as the faith I spoke of. You know your own weakness and are modest; but you know that man has in him that unspeakable somewhat which makes him capable of miracle, able to lift himself by the might of his own soul, unaided, able to face annihilation for a blind belief.

RTWT

HT: Bird Dog.

23 May 2018

Adult leg bones were gathered from the battlefield and arranged in the wetlands along with non-local stones.

National Geographic:

Archaeologists excavated 2,095 human bones and bone fragments—comprising the remains of at least 82 people—across 185 acres of wetland at the site of Alken Enge, on the shore of Lake Mossø on Denmark’s Jutland Peninsula. Scientific studies indicate that most of the individuals were young male adults, and they all died in a single event in the early first century A.D. Unhealed trauma wounds on the remains, as well as finds of weapons, suggest that the individuals died in battle.

The team didn’t dig up the entire 185 acres, but the researchers extrapolated that more than 380 people may have been interred in boggy waters along the lakeshore some 2,000 years ago, based on the distribution of the remains that were excavated. ….

An army of several hundred people far exceeds the population scale of Iron Age villages in the region, the new paper notes, suggesting that a war band of this many men required the right kinds of organization and leadership skills to recruit fighters from far distances. …

Here’s where it gets really interesting: Many of the human remains show animal gnaw marks consistent with bodies left exposed somewhere else for six months to a year before being submerged in the wetland. Others bones are deliberately arranged in bundles with stones brought in from other areas, and in one case, fragments of hip bones from four different individuals were threaded on a tree branch.

This leads researchers to suspect that after a period of time, the remains were collected from an yet-to-be discovered battlefield and ritually deposited in the marsh. However, the southern areas of the site also revealed many very small bones, which could easily be overlooked when gathering skeletonized remains. This may indicate archaeologists “could actually be very close to the actual battle site,” says study coauthor Mads Kähler Holst, an archaeologist at Aarhus University and executive director of the Mosegaard Museum.

Noting the millennia-long ceremonial and ritual importance of bogs and shallow lakes across northern Europe, Bogucki believes the removal of bodies from the battlefield after a period of time and their interment in the marsh may likely be the action of the victors trying to memorialize their triumph. …

Although they battled Germanic tribes across much of Europe in the first century A.D., Roman armies never made it as far north as southern Scandinavia, and the team didn’t find evidence for direct Roman involvement in this battle.

“The trauma [on the bodies] is also consistent with what we would expect from an encounter with a well-equipped Germanic army,” adds Holst.

Bogucki agrees: “This was barbarian-on-barbarian.”

RTWT

15 Nov 2016

Frank Holl, Did you ever kill anybody Father?, 1883, Private collection.

Sold by Christies London 17 June 2014, GBP 74,500 (USD 126,426).

“She is holding what appears to be a British Pattern 1827 Rifle Officer’s Sword or a Pattern 1845 Infantry Officer’s Sword.”

———————————-

I asked the same question as a child to my father, who had served in the Third Marine Division on Guadalcanal, Vella LaVella, Rendova, Guam, and Iwo Jima. He looked embarrassed, paused for a moment, and replied: “Oh, you know, we were all shooting at them, and they were falling down, and you couldn’t tell who had hit them…”

Hat tip to Karen L. Myers.

07 Oct 2016

rangordnung:

Marx had asked “Is Achilles possible with gunpowder and lead?†Jünger has answered, “That was my problem.â€

16 Aug 2016

An Argentine ant (Linepithema humile) attacks a much larger fire ant (Solenopsis invicta).

Every now and then there is a good question and answer on Quora. Someone asked: “Do animals fight wars and if so what was the largest war?”

Zoologist Suzanne Sadedin replied:

The largest war in animal history — in fact, by numbers the largest war in history — is going on right now.

Once upon a time there was a tiny brown ant who lived by a swamp at the end of the Paraná River in Argentina. Her name, Linepithema humile, literally means “humble†or “weakâ€. Some time during the late 1800s, an adventurous L. humile crept away from the swamp where giant river otter played and capybaras cavorted.

She stowed away on a boat that sailed to New Orleans. And she went to war.

At home in the Paraná delta, L. humile nests would ferociously defend themselves from other nests, both of their own species and other kinds of ant. It was a life of never-ending territorial skirmishes, where nobody could really get ahead. When two L. humile met, they would flick their antennae over each others’ bodies, tasting the combination of hydrocarbons on their skin. This flavor would tell them whether the stranger belonged to the same nest. If she tasted familiar, she would be recognized as a sister. She would be gently stroked, offered food and welcomed into the nest. But if the flavor were not recognized, the ants would try to kill each other.

In New Orleans, something changed. L. humile, invading the United States, spread like wildfire. Instead of forming discrete, competing colonies, they behaved as a united army. They would brutally attack ants of other species, but welcome every L. humile as a long-lost sister in arms. Like L. humile in Argentina, other species of ants in the US must defend their territories against their own species. This gives the cooperative L. humile a huge strategic advantage; they waste neither lives nor energy on fighting with their own kind, but focus ruthlessly upon species-level conquest. Though individually tiny, they can swarm over native ants many times their size.

The supercolony grew to cover most of the United States. Then it spread to England, Europe, Japan, Australia and New Zealand. L. humile is now abundant on every continent except Antarctica, and wherever she goes, she slaughters native ant species.

How did she do this? Did inbreeding reduce the diversity of hydrocarbons on the ants’ skin, such that they no longer saw one another as enemies, but as sisters? Did natural selection tone down L. humile’s territorial instincts to suit their environment, so they would react aggressively only to the strong stimulus of another species? It seems likely both mechanisms were involved.

Things have not been perfect. Near San Diego, a schism formed, and a separate supercolony was created. The battlefront extends for miles; some 30 million ants die there every year. Another super-colony has formed in Catalonia. Perhaps as L. humile eliminates her competitors, her alliance will fracture entirely into squabbling tribes. But for now, from Europe to the United States, all the way to New Zealand, a global megacolony still persists, consisting of around 1 trillion individuals: a humble brown ant united in war against every other ant alive.

People always talk about the meek inheriting the earth. In L. humile’s case, it’s clearly working.

————————————-

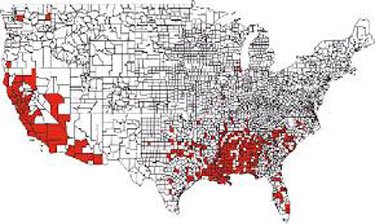

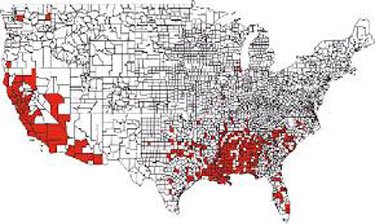

L. humile distribution by US county

28 Jul 2016

Buckwheat groats and mushrooms

Jill Dougherty found alarming seasonal signs in Russia and in bordering regions.

Recently, I grabbed a taxi in Moscow. When the driver asked me where I was from, I told him the United States. “I went there once,†he said, “to Chicago. I really liked it.â€

“But tell me something,†he added. “When are we going to war?â€

The question, put so starkly, so honestly, shocked me. “Well, I hope never,†I replied. “No one wants war.â€

At the office I ask a Russian employee about the mood in his working-class Moscow neighborhood. The old people are buying salt, matches and “gretchka,†(buckwheat) he tells me – the time-worn refuge for Russians stocking up on essentials in case of war.

In the past two months, I’ve traveled to the Baltic region, to Georgia, and to Russia. Talk of war is everywhere.

Hat tip to Vanderleun.

02 Jun 2016

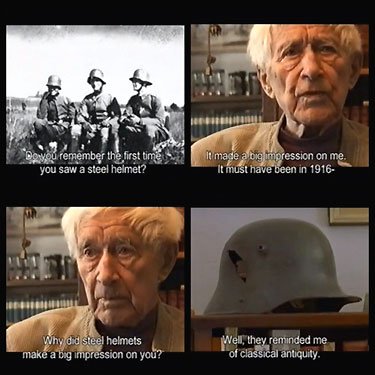

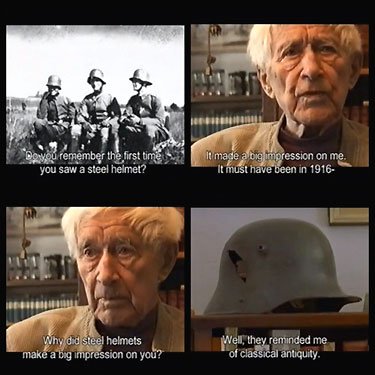

Ernst Jünger (1895-1998)

Karl Marlantes (Y ’67), who served as an officer in the Marine Corps, received the Navy Cross, and wrote perhaps the best Vietnam War novel, is pretty much the ideal choice to write the introduction for the new Penguin Classics edition of Ernst Jünger’s WWI memoir Storm of Steel.

[L]ike Jünger, who observed the stream of colored flares, I can appreciate that, borrowing a phrase from Yeats, there is a terrible beauty about war, even though I’m not a born warrior. I remember watching enemy tracers seeming to float into the night sky over Laos, seeking to down one of our airplanes, in much the same way I’d watch fireworks. I remember even being enthralled, late in my tour when I’d been transferred to an air obÂserver squadron, by green tracers flying by both windows of our OV-10 as we dived firing, head to head with an NVA antiaircraft gun. Jünger sees the beauty—it’s everywhere in his memoir—and perhaps you will see it too. This doesn’t need to change how you judge war; coral snakes and tsunamis are beautiful too.

Jünger writes about many things other than combat, but all take us into the trenches as he saw them. He writes about fear and panic. He writes about nature—about having to live outside, just like a wild animal, in all of nature’s cruelty and beauty. He writes about the code of honor and manliness that engenders mutual respect beÂtween soldiers on opposite sides of the battle, as when he encounÂtered a young British officer just before Christmas during a poignant temporary truce that unfortunately went bad:

We did, though, say much to one another that betokened an almost sportsmanlike admiration for the other, and I’m sure we should have liked to exchange mementoes.

At another point he writes:

Throughout the war, it was always my endeavour to view my opponent without animus, and to form an opinion of him as a man on the basis of the courage he showed.

And he writes about the understated and often gallows humor that goes hand in hand with the code of honor and manliness. I remember in Vietnam a kid waiting to be medevaced, gasping for air because he’d taken a bullet through one lung, saying, “You know, sir, it ruined my whole day.†Jünger often uses such humor:

We suffered many casualties from the over-familiarity engendered by daily encounters with gunpowder. My dugout was somewhat changed as well . . . the British had fumigated it with a few hand-grenades. We were so abundantly graced with trench mortars . . .

In another scene, Jünger describes a fierce skirmish with IndiÂan soldiers from the First Hariana Lancers:

With only twenty men we had seen off a detachment several times larger, and attacking us from more than one side, and in spite of the fact that we had orders to withdraw if we were outnumbered. It was precisely an engagement like this that I’d been dreaming of during the longueurs of positional warfare.

I’d have been dreaming of my high school girlfriends.

“These short expeditions,†Jünger writes, “where a man takes his life in his hands, were a good means of testing our mettle and interrupting the monotony of trench life. There’s nothing worse for a soldier than boredom.†I would say homesickness, hunger, hypothermia, getting gassed, gangrene, and trench foot, not to mention getting killed or maimed, would all be worse than boredom. But Jünger was different.

Read the whole thing.

21 Apr 2016

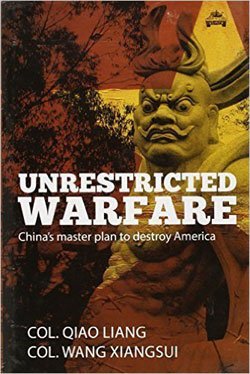

David Barno and Nora Bensahel identify the most important strategic book you haven’t read.

In 1999, two Chinese colonels wrote a book called Unrestricted Warfare, about warfare in the age of globalization. Their main argument: Warfare in the modern world will no longer be primarily a struggle defined by military means — or even involve the military at all.

They were about a decade and a half before their time.

Colonels Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui argued that war was no longer about “using armed forces to compel the enemy to submit to one’s will†in the classic Clausewitzian sense. Rather, they asserted that war had evolved to “using all means, including armed force or non-armed force, military and non-military, and lethal and non-lethal means to compel the enemy to accept one’s interests.†The barrier between soldiers and civilians would fundamentally be erased, because the battle would be everywhere. The number of new battlefields would be “virtually infinite,†and could include environmental warfare, financial warfare, trade warfare, cultural warfare, and legal warfare, to name just a few. They wrote of assassinating financial speculators to safeguard a nation’s financial security, setting up slush funds to influence opponents’ legislatures and governments, and buying controlling shares of stocks to convert an adversary’s major television and newspapers outlets into tools of media warfare. According to the editor’s note, Qiao argued in a subsequent interview that “the first rule of unrestricted warfare is that there are no rules, with nothing forbidden.†That vision clearly transcends any traditional notions of war.

Unrestricted Warfare was an explicit response to the reigning Western military orthodoxy of the time. The preface is dated January 17, 1999, which the authors note was the eighth anniversary of the outbreak of the 1991 Gulf War. In many ways, their argument refuted many of the Western lessons drawn from that conflict: that wars could be short, sharp, and dominated by high-technology weaponry used with stunning precision to shatter an enemy’s armed forces in hours or days.

Read the whole thing.

/div>

Feeds

|