Remember, remember!

The fifth of November,

Gunpowder, treason, and plot;

There is no reason

Why the Gunpowder treason

Should ever be forgot!’

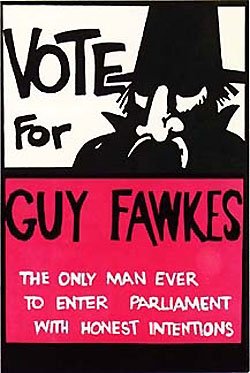

Early in the morning of November 5, Guy Fawkes crept, torch in hand, into the cellar beneath the House of Lords in the Palace of Westminster. In that cellar, he and his fellow conspirators had previously placed a cache of 1800 pounds ((36 barrels, or 800 kg) of gunpowder. Just as he was about to ignite the barrels, blowing himself and the House of Lords to Kingdom Come, the torch was snatched from his hand by a man named Peter Heywood.

Fawkes was arrested and taken before the privy council where he remained defiant. When asked by one of the Scottish lords what he had intended to do with so much gunpowder, Fawkes answered him, “To blow you Scotch beggars back to your own native mountains!”

So went the attempted Gunpowder Plot of 1605.

The intention of the plotters was to use the explosion, timed to coincide with the opening of Parliament, to kill King James I and eliminate much of the ruling Protestant aristocracy. They also intended to kidnap the royal children, then raise the standard of revolt in the Midlands with the object of restoring the freedom to practice Catholicism in England.